I.

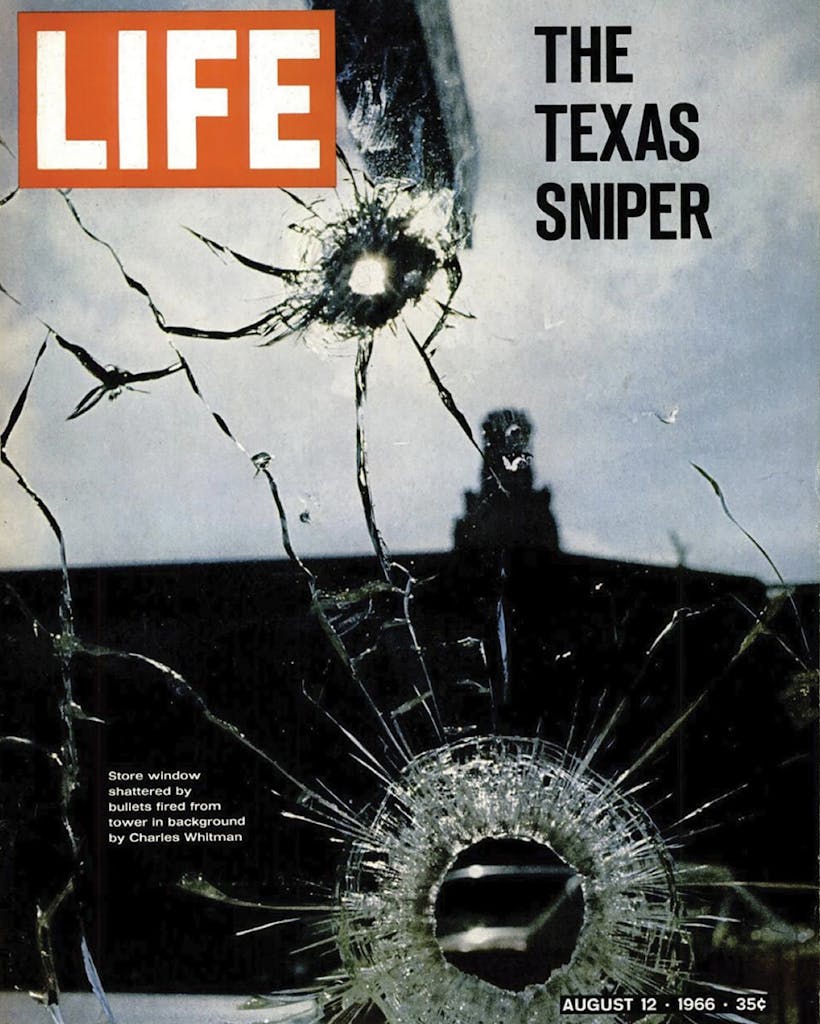

In the spring of 1967, when Claire Wilson was a freshman at the University of Texas, she went to the library one afternoon to track down an old copy of Life magazine. Thumbing through a stack of back issues, she scanned the dates on their well-worn covers. Finally she arrived at the one she was looking for, and she slid it off the shelf. On the cover was a stark black and white photograph of a fractured store window, pierced by two bullet holes; in the distance loomed the UT Tower. Above the university’s most iconic landmark were three words in bold, black letters: “The Texas Sniper.”

Claire sat down and studied the large, color-saturated pictures inside, turning the pages as if she were handling a prized artifact. She read how Charles Whitman, an architectural engineering major, had brought an arsenal of weapons to the top of the Tower on August 1, 1966, and trained his rifles on the students and faculty below, methodically picking them off one by one. She pored over the images of people crouching behind cars as the massacre unfolded, and the aerial photo of campus dotted with red X ’s showing where Whitman had hit his intended targets.

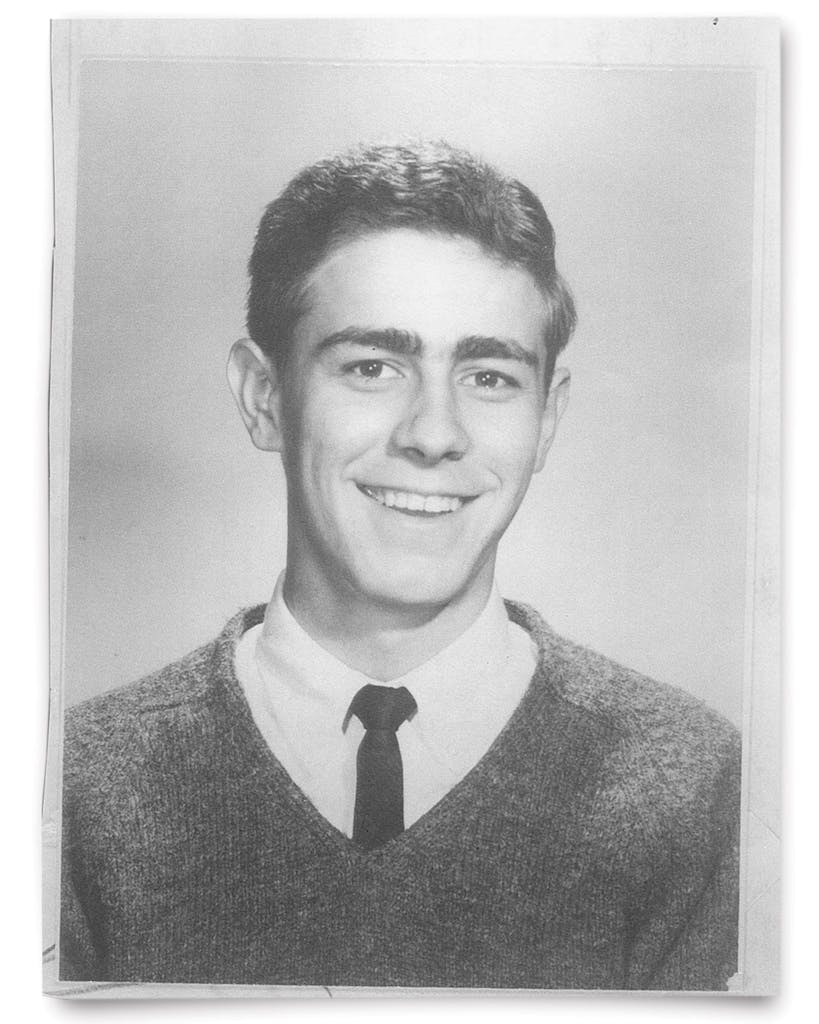

On the list of those killed, she located the name of her boyfriend, Thomas Eckman. Her gaze fell on Tom’s picture, in which he sat in the formal pose of all mid-century yearbook photos, smiling broadly, his tie tucked into his V-neck sweater. Claire stared into his eyes, tracing the contours of his face. Holding the magazine in her hands, she felt some reassurance that what she had witnessed on campus that day had actually happened.

Not that she needed proof: above her left hip was a gnarled indentation, not yet healed, where one of Whitman’s bullets had found its mark. She had been hospitalized for more than three months after the killing spree, spending what was supposed to have been the fall semester of her freshman year learning how to walk again. But by the time she returned to UT, in January, the tragedy had become a taboo subject on campus. Absent were the protocols that would later come to define school shootings: the grief counselors, the candlelight vigils, the nationwide soul-searching. Whitman’s crime—decades before Columbine, Virginia Tech, and Newtown became shorthand for on-campus depravity—was unprecedented, and there was no language for it yet. The mass shooting was an obscenity whose memory stained the university, an aberration to be forgotten, and in the vastness of that silence, Claire found herself second-guessing what she remembered. The few times her friends tiptoed around the subject, they referred to it as “the accident.”

The person Claire longed to talk with most was gone. She had known Tom for only a few months, but they had been inseparable. They had met as summer-school students in May 1966, when she was five months pregnant and single—a scandalous state of affairs for a middle-class girl from Dallas, though Claire had never cared much for social conventions. Tom, who was also eighteen and new to Austin, had moved in with her on the spot. Claire had had no interest in getting married—the institution was an anachronism, as far as she was concerned—and Tom, whose parents had divorced when he was little, felt the same way.

Like her, Tom attended Students for a Democratic Society meetings and saw himself as a foot soldier in the civil rights movement, once driving with her to the Rio Grande Valley to stand in solidarity with striking farmworkers. The two passed whole afternoons on the screened-in porch they used for a bedroom in their house off-campus, quoting favorite passages to each other from the novels they were reading: he, Joyce Cary’s The Horse’s Mouth and she, Lawrence Durrell’s The Alexandria Quartet. Sometimes Tom pressed his hand to her belly to see if he could feel the baby move.

In the wake of the shooting, Claire tried to hold moments like these in her mind. But her thoughts often wandered back to that August morning, when she and Tom had set out across the South Mall—and then she would be there again, on that blisteringly hot day, walking on the wide-open stretch of concrete beside him.

The anthropology class they were taking had let out early, sometime after eleven o’clock. Claire and Tom walked to the Chuck Wagon, the cafeteria inside the Student Union where campus leftists and self-styled bohemians held court, and happened to run into an old friend of Tom’s from junior high. Eager to catch up, the ex-classmate suggested that they go to the student lounge to shoot some pool. Tom explained that he and Claire had to feed the parking meter first; downing his coffee, he promised they would be right back.

Tom and Claire stepped out into the thick, midday heat and headed east under a canopy of live oak trees. Tom was sporting a short-sleeved plaid shirt and his first mustache. Claire was wearing a brand-new maternity dress he had picked out, a beige shift with a flowery ribbon around the yoke. She was eight months along by then, and she could feel the weight of the baby as she walked. When they reached the upper terrace of the South Mall, the live oaks receded, and they were suddenly out in the open, exposed under the glare of the noon sun.

To their left stood the Tower, the tallest building in Austin after the Capitol; to their right stretched the mall’s green, sloping lawn. As was often the case, they were deep in conversation; they had just begun a discussion about Claire’s spartan eating habits and Tom’s concern that the baby was not getting proper nutrition. Claire was in the middle of saying that she had, in fact, had a glass of orange juice that morning when a thunderous noise rang out. An instant later, she was falling, her knees buckling beneath her. Bewildered, Tom turned toward her. “Baby,” he said, reaching for her. “What’s wrong?” Then he too was knocked off his feet.

The two teenagers collapsed onto the pavement beside each other. Claire was flat on her back, the arc of her abdomen rising up in front of her. She felt as if a white-hot electric current was coursing through her. Tom lay to her left, close enough to touch, his head turned away from her. She called out to him, but he did not answer.

At first, no one on the South Mall seemed to realize what was happening. A man in a suit and tie ordered Claire and Tom to get up, ignoring her pleas for a doctor as he breezed by. She realized he thought it was a stunt—guerrilla theater or an antiwar protest, maybe, judging from his contempt. Moments later, she heard screams and the frantic cries of other students as they scattered, ducking for cover.

Bullets rained down from above, dinging balustrades, shattering windows, kicking loose concrete. A dozen yards from her and Tom, a physics professor was felled in mid-stride as he descended the stairs to the mall’s lower terrace; his body would remain there, sprawled across the steps beside the bronze statue of Jefferson Davis, as students crouched behind the trees and hedges nearby. On the lawn, a young woman in a blue dress with nowhere to hide cowered behind the concrete base of a flagpole. Claire looked up at the Tower, where every now and then the nose of a rifle edged over the parapet, followed by the crack of gunfire and a wisp of smoke. She wondered if the Vietnam War had somehow come to Texas.

Every fifteen minutes, the Tower’s bell would chime, but it was nearly half an hour before the sound of sirens neared, and even then, no help came. A police officer who was advancing behind a stone railing, service revolver drawn, was swiftly shot in the neck. Unable to lift herself, Claire remained where she had fallen, marooned. Blood pooled beneath her, saturating her dress. She played dead as the sound of gunshots reverberated around her, echoing off the red tile roofs and limestone walls. Dozens of students had run home to retrieve their deer rifles, and the echo of return fire rang out as they came back to take aim at the gunman.

It was nearly one hundred degrees by then, and she ached to get off of the concrete, which scorched her bare legs. When the heat became unbearable, she bent her right knee just enough to lift her calf, half expecting to be torn apart by gunfire. She did not know whether to feel relief or dread when she was not. She feared that Tom was dead, and that her child was lost too; instead of the thrumming energy she usually felt inside her, the baby had become still.

A young woman with long red hair suddenly ran into her field of vision, offering to help. “Lie down quick so we don’t get shot,” Claire pleaded. The woman dropped to the pavement and, from the spot where she lay, a few feet away, tried to keep Claire conscious by peppering her with questions. What classes are you taking? Where did you grow up? Claire whispered a few words back, struggling to answer.

Finally, more than an hour after the shooting had begun, three young men bolted from their hiding places and sprinted toward her and Tom. One grabbed Claire’s arms, the other her ankles, and together they ran as her body dangled between them. The third man hoisted Tom’s wilted frame into his arms, steadying himself under the weight of the teenager’s lifeless body before following close behind.

As they raced across the mall, Claire did not feel the penetrating pain of her injuries or realize that she was losing copious amounts of blood. She could not make sense of what had just happened, much less begin to fathom how the jagged path of one bullet had, in a single moment, redrawn her life’s course forever. She knew only that if she were lucky, she might live.

II.

Growing up, Claire had never thought of guns as something to fear. As a kid she had taken riflery at summer camp in East Texas, where she had delighted in the thrill of target practice. Her parents kept guns in their house in East Dallas—her father, a bird hunter and ex-Marine, stashed his long guns in the closet, where they leaned up casually against the wall. Guns were intertwined in her family history; they had made Texas passable for her Tennessee-born ancestors, who received a land grant from Stephen F. Austin in the 1820s. At age twelve, her maternal grandfather had used the proceeds from his initial cotton harvest in Brazoria County to buy his first rifle.

Even when President Kennedy was assassinated, Claire did not blame gun violence but rather the culture of intolerance that gripped her hometown. She knew all too well what it meant to be an outsider in Dallas: at a time when the John Birch Society and archconservative oil magnate H. L. Hunt held sway over the city, her father, John, had dedicated his legal career to representing clients, many of them black, in worker’s compensation cases. Her mother, Mary, was the local precinct chair for the Democratic party, so consumed by her work championing various liberal causes that Claire came to measure time in election cycles.

Though the Wilsons lived only one block from the Lakewood Country Club, they refused to join, leaving Claire and her four siblings to make the long walk to the municipal pool—which was also closed to blacks but at least welcomed their Jewish friends. Not wanting Claire, the eldest, to be oblivious to the injustices beyond their privileged, all-white enclave, her father drove her on more than one occasion through West Dallas, then home to a toxic lead smelter and slums that lacked sewage systems and running water. When she was twelve, her father took her to see Martin Luther King Jr. speak at the Majestic Theater, in Fort Worth, where few whites were present; at a private reception afterward, he led her up to the young minister to shake his hand.

At the time, in the late fifties, the unspoken rules of segregated society seemed immutable to Claire. When her parents went out to dinner one night with a black couple they knew, she watched, frozen, as the four drove off in her parents’ Cadillac, convinced they would all be murdered. By the time she was a teenager, however, she had grown impatient with the pace of change. Each day for a month during the summer of 1964, she donned a dress, hat, and white gloves and headed downtown with her mother to take part in the protests outside the Piccadilly Cafeteria, a popular restaurant that refused service to blacks. Claire was arrested and booked into the city jail, but the charges were dismissed. She was ridiculed for being a “nigger lover” when she returned that fall to Woodrow Wilson High School, an epithet she doubled down on when she spent the following summer in the Mississippi Delta working as a volunteer with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. So immersed did she become in the SNCC’s effort to get black residents registered to vote that she stayed on until October, content to miss her senior year.

Late that fall, she ran into John Muir, an acquaintance who had come home to Dallas unexpectedly from his sophomore year at Columbia University. Muir was wrestling with whether to drop out of college and devote himself to the civil rights movement. A graduate of the elite St. Mark’s School of Texas, Muir was charismatic and well read, and though he was white, he had served as vice president of the local NAACP Youth Council. Claire had gotten to know him during the summer of the Piccadilly protest, when a multiracial group of teen activists had regularly gathered at her parents’ house. During those unhurried afternoons, Muir had introduced her to the works of E. E. Cummings and Joseph Heller and played her the first Bob Dylan album she had ever heard, but it was not until Christmas week in 1965, after Claire had returned from Mississippi, that they slept together.

Muir decided to return to Columbia after the holidays, but first he agreed to help Claire move to Austin. Her parents, whose marriage had been foundering for years, had recently divorced, and she saw no compelling reason to stay in Dallas. Before long, Claire had landed a job waiting tables in her new city and enrolled for night classes at Austin High. She felt at home in the sleepy capital, a place of cheap rent, psychedelic rock, and nascent political activism. Her involvement in the civil rights movement quickly won her respect and friends, and she fell in with a group of like-minded UT students who were ablaze with new ideas.

It was in the midst of this happy-go-lucky time—when she was finally free from the judgments of racist classmates and the near-constant threat of violence she had felt in Mississippi—that Claire discovered she was pregnant. Muir dutifully made a trip to Austin after she told him the news, but during their discussions about how to move forward, he never suggested they make a life together. While she had no desire to get married, Claire felt bruised by the rejection. Muir returned to Columbia, leaving behind the then-considerable sum of $200 so she could have an abortion.

On the advice of friends, Claire met with a woman who knew how to procure the illegal—and, at that time, often perilous—procedure. But she could not bring herself to go any further. Though her decision to keep the baby would have meant certain exile from most social circles, in her group of free-thinking friends, her pregnancy was of little concern. Privately, the idea of having a child thrilled her, but it was not until she met Tom that May that someone shared in her joy.

“I was really, truly happy for the first time in my life,” Claire told me. “I was out on my own, and I was in love, and I had so many friends. We were revolutionizing the world, and Tom and I were at the front of it.”

Whitman hit his targets with terrifying precision. Across a crime scene that spanned five city blocks, the former Marine sharpshooter managed to strike his intended victims with ease, felling them from distances well beyond five hundred yards. His arsenal included a scoped 6 mm Remington bolt-action rifle; a .35-caliber pump rifle; a .357 Magnum Smith & Wesson revolver; a .30-caliber M1 carbine; a 9 mm Luger pistol; a Galesi-Brescia .25-caliber pistol; a twelve-gauge shotgun with a sawed-off barrel; and about seven hundred rounds of ammunition. His rampage dragged on for more than an hour and a half before Austin police officers Ramiro Martinez and Houston McCoy reached him on the Tower’s observation deck and shot him dead. By the time it was all over, Whitman had succeeded in killing 16 people and wounding 31.

Claire’s rescuers miraculously avoided being hit as they ran headlong toward the western edge of the mall, spiriting her to the shelter of the Jefferson Davis statue. From there, five bystanders took over, carrying her to Inner Campus Drive, where they loaded her into a waiting ambulance.

She would be one of 39 gunshot victims delivered to Brackenridge Hospital’s emergency room in the span of ninety minutes. Many of them were bleeding out quickly, and doctors and nurses shouted back and forth as they tried to discern who should be sent into surgery first. Claire and a seventeen-year-old high school student named Karen Griffith, who had been shot in the lung, were lying on gurneys beside each other, waiting to be X-rayed, when a doctor intervened. “There’s no time for X-rays,” he yelled, directing his staff to prep them both for surgery.

Claire was still conscious when a medic began cutting off her blood-soaked dress, and she begged him to stop, not wanting to lose the garment Tom had picked out for her. Though she clung to the delusion that she had only been shot in the arm, her magical thinking did not extend to Tom, whom she felt certain was dead. She had seen his inert body as she was lifted away.

Claire was put under general anesthetic, and her doctors set to work. The full extent of the damage was not evident until they made a lengthy incision down her torso, from sternum to pubic bone. The bullet had torn into her left side just above the hip, splintering the tip of her pelvis, puncturing her small intestine and uterus, lacerating an ovary, and riddling her internal organs with shrapnel. A C-section was performed, but the baby—a boy—was stillborn. A bullet fragment had pierced his skull.

The operation took twelve hours. Not long after Claire regained consciousness, she was wheeled down a corridor to the ICU. Standing along the walls on either side were her friends, who had waited at the hospital until past midnight to learn if she had made it out of surgery. “We love you, Claire!” they called out.

She spent the next seven weeks in the ICU in a fog of Demerol and Darvon. All told, she would endure five operations at Brackenridge to repair the damage done to her. To distract herself from the pain, she would belt out protest songs from her bed, delivering renditions of “Which Side Are You On?” and “We Shall Overcome” at the top of her lungs. With no TVs or even visitors, besides family members, allowed inside the ICU, she had few distractions and little information about life outside Brackenridge. Despite being a victim in a tragedy that had made headlines around the world, she never saw or heard a single news report about the shooting.

Her life narrowed to her hospital bed and the green floor-to-ceiling curtains the nurses drew tightly around her, past which she could sometimes catch sight of a tree and a sliver of sky. Intravenous lines extended from all four of her limbs, and her left leg, which was in traction, was suspended above her. Every two hours, in an excruciating ritual she came to dread, a nurse would turn her, rolling her onto one side and then the other. Her mother, who tried to project an image of strength, often sat at her bedside, chatting with the doctors and offering Claire words of encouragement. Refusing to give in to the chaos that the shooting had wrought, she was always immaculately dressed, often wearing a two-piece knit suit from Neiman Marcus, her blond hair pulled into a French twist.

If Claire’s mother or her doctors ever explicitly told her that her baby was stillborn, she struck it from her memory. No one, as far as she could recall, ever spoke aloud the fact that her child had died. That the baby was a boy, and that a burial plot had been secured for him, were the only details she gleaned. Claire did not ask questions because she already knew; she felt his absence. She was startled when her milk came in days after the C-section, leaving her breasts engorged, and relieved when it dried up and her baby weight fell away. Her body settled back into its old contours, her belly flat, as if the pregnancy had never happened.

Without the chance to hold the baby in her arms, Claire did not know how to mourn his loss; she had not yet chosen a name, and he felt like an abstraction, his face unknowable. But her grief for Tom, and their abbreviated summer together, only metastasized once the fall semester got under way. She was tormented by the fact that she had not been able to attend his funeral. “I learned more in those [months with Tom] than perhaps in any other period of my life,” she wrote in a four-page condolence letter to his father. “The sort of things that were between Tom and me happen so rarely in this world that most people don’t even understand the language.”

Most of the shooting victims who had been admitted to Brackenridge were discharged; some, like Karen Griffith, did not survive. Only Claire stayed on, her presence noted every now and then in the local paper, which ran a two-sentence squib on September 16 announcing that she was the last of Whitman’s victims to remain hospitalized.

The myriad complications of abdominal gunshot wounds, including the threat of infection and sepsis, made Claire’s condition tenuous. By the time her surgeries were complete, several feet of her intestine had been removed, as well as an ovary and the iliac crest of her pelvic bone. Daily physical therapy sessions allowed her to gradually regain the ability to walk. After she was moved out of the ICU, she became adept at using a cane, and at night, when she was unable to sleep, she would maneuver her way to the nurses’ station to visit with the women in starched white uniforms who cared for her, some of whom were not much older than she was.

Claire was finally released the first week of November. She was nineteen by then, though she felt a thousand years old. She returned to campus in January, and in the early spring, she made the first of several visits to the library to page through the August 12 issue of Life. She had no pictures of Tom, and though the yearbook photo featured in the magazine failed to capture his spirit, she liked to study it all the same.

The confirmation she sought about the massacre—that she had not dreamed or invented it—was muddled by the fact that Life, like most publications at the time, omitted her preterm baby from the official tally of the dead. And so rather than avoid the South Mall on her way to class each day, she purposely walked past the spot where she and Tom had been hit, intensely curious, as if her proximity to the crime scene would render it more vivid. When the Tower’s observation deck was reopened that June, she visited it by herself, riding the elevator to the twenty-seventh floor and then taking three short flights of stairs to the top, just as Whitman had with his arsenal. She looked over the balustrade down at the mall, as he had, and crouched down to peer through the downspouts where he had rested the barrel of his gun.

Austin was a place that had brought her so much happiness, but as she surveyed campus and the city that spread out beyond it, she felt an overwhelming sense of dislocation. How would she ever recover from the enormity of her loss, she wondered, or navigate the years ahead? “I was so lonely and so longing for some sort of physical contact,” Claire said. “All I wanted right then was for somebody to put their arms around me and hold me tight.”

III.

Ten years after the shooting, on a warm July afternoon in 1976, Claire stood in a phone booth in northern Colorado, not far from the rugged peaks of the Continental Divide, with the receiver pressed to one ear. She had agreed to speak to an Austin American-Statesman reporter named Brenda Bell who was interviewing survivors of the shooting for an article that would mark its ten-year anniversary. With the help of Claire’s father, Bell had tracked Claire down in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, outside the small town of Loveland. Claire had never spoken about the shooting publicly, and her voice was soft as she answered the reporter’s questions.

After she had been shot, she told Bell, she was “basically mixed up—confused about life in general.” Only once she started reading the Bible in the years that followed had she found some peace. Scripture, she explained, “started effecting a lot of changes in my life.” She had found a group of Seventh-day Adventists who worked as medical missionaries around Loveland, where they tried “to help other young people physically, mentally, and spiritually,” she said. Her time there, immersed in nature and the gospel, had been restorative. “I’m so thankful,” she told Bell before she hung up. “I’m glad to be alive.”

Claire had spent five years living and working at the Eden Valley Institute, a spiritual retreat accessible only by unpaved roads and bounded by jaw-dropping panoramas of the snow-capped Rockies. Its clean-living, Adventist doctrine rejected not just smoking, drinking, and sex outside marriage but also the distractions of popular culture. In an era defined by the loosening of social mores, it was a monastic existence; Claire did not watch the evening news, listen to the radio, or go to the movie theater. While some women worked on the institute’s farm, which yielded much of their food, or helped with the cooking and childcare, her main occupation was teaching the residents’ school-age children. (Her father approvingly told her on his first visit that the self-sustaining community was “the closest thing to Red China” he had ever seen.) Though newspapers could be found at Eden Valley, Claire steered clear of them, preferring to spend her free time taking long walks through the backcountry. She was unaware of the Watergate hearings or the fall of Saigon. “It was very healing to be way out, deep in the mountains, apart from the rest of the world,” Claire told me.

She had tried at first to heal herself in more conventional ways, visiting UT’s Student Health Center as early as 1967 for the talk therapy she believed she urgently needed. But after her first session, during which she felt that the psychologist had made a pass at her, Claire abandoned the idea. At her father’s urging, she transferred to the University of Colorado at Boulder that fall, leaving the near-constant reminders of the shooting behind, but she was homesick there, and she returned to UT the following year.

To her friends, she had seemed fine—“nice and sunny,” recalled one—but not long after her return, she landed at the Student Health Center again when she abruptly stopped eating. The psychiatrist who evaluated her, Claire thought, showed more interest in her admission that she had taken LSD before than in her obvious depression. He put her on Thorazine, a powerful antipsychotic, and though her hair began falling out and she struggled to concentrate in class, her treatment was not adjusted. “Questioning doctors was just not done then, so I was an obedient patient,” she told me. “There never was any talk therapy. He only wanted to discuss my past drug experiences, which were so few.” In 1969, at the end of her spring semester, she dropped out and moved back to Colorado.

It was that same year that Claire began to feel the stirrings of belief. “After the shooting, I’d started wondering what forces were at work in the universe,” she said. “I felt strongly that there was a force I couldn’t see, and I was interested in finding out what it was.” She escaped to the mountains outside Boulder with a University of Colorado student named Ernie, with whom she lived in a rough-hewn house in the woods with no indoor heat or plumbing. They immersed themselves in nature and back-to-basics living, warming themselves by a coal stove and hauling water from a well.

Just down the road from them and the other hippies who had taken up residence in Lefthand Canyon was an 82-year-old woman named Emma Spencer, whom her neighbors called “Ma.” A Seventh-day Adventist, she grew her own food, wove rugs by hand, and strictly observed the Sabbath. To Claire, the child of nonbelievers, she was a source of fascination. Ma gave her a Bible, which she began to read, and one afternoon, Claire found herself kneeling in prayer beside the older woman, searching for words as she tried to communicate with God. She had cried for Tom many times, but as she knelt on the knobby rag rug in Ma’s log cabin, she felt, as she would later recall, an “unbidden and unexpected” grief surface for the baby. For the first time, Claire began to weep for her lost son.

Her desire for “a sincere, authentic, Christian life,” as she called it, took her to Eden Valley in 1971. She would remain there until she was thirty, not striking out on her own until the winter of 1977. Her friends in Texas and Colorado, who heard from her infrequently during this time, if at all, were stunned that the girl they knew, who delighted in skinny-dipping and challenging the status quo, had suddenly gotten religion. “I don’t know what combination of PTSD, spiritual yearning—which was very much of the moment—depression, and epiphany led her to the strict regime of the Seventh-day Adventist utopia,” observed Tim Coursey, a childhood friend. “But I do remember thinking, ‘Well, how about that? She walked right through the looking glass.’ ”

The dream, which Claire first had in her twenties, always began the same way: she would look down and discover her baby, bright-eyed, in her arms. He was never as small as a newborn—he would be a few months old, perhaps, or a toddler, even, old enough to meet her gaze—and she would be flooded with relief as she stared back at him in wonder. Then she would glance away, or walk into another room, her attention wandering for no more than a second, and when she looked back, her son would be gone.

Claire did not have the dream frequently, but when she did, in the peripatetic years that followed her time at Eden Valley, she awakened with a start, a deep ache in her chest. As she moved from Colorado to other states in the West—New Mexico, Texas, and Wyoming—she would occasionally stop in a public library to see if she could find the old Life magazine, anxious for something concrete upon which to anchor her longings. In those analog days, before it was possible to conjure up information about anything with a few keystrokes, her personal history was relegated to microfilm reels and hardbound magazine volumes, and there, alone among the stacks, she would scrutinize Tom’s photo again. People she met had sometimes heard she was the victim of gun violence—one rumor at Eden Valley placed her at the 1970 Kent State shootings—but she rarely shared her story.

After Eden Valley, Claire made a brief sojourn to another religious community in upstate New York and then headed to New Mexico, where her sister, Lucy, was working as a psychologist at a residential facility for developmentally disabled adults. It was there that Claire met her first husband—an easygoing teacher who ran the facility’s art therapy program—and they wed in 1979. She never discussed the shooting with him, and he never showed any interest in discussing it. “I really just wanted to be married and have a baby, and that was more important to me than whether we were a good match,” Claire said. They were not, and within two years they had divorced.

Claire packed her belongings and headed to Stephenville, Texas, where she moved in with her grandmother and enrolled in Tarleton State University, determined to finally finish college. She did so two years later, in 1983, with honors, when she was 35 years old. Armed with a degree in education, she then made her way to Wyoming, where she taught at a private Seventh-day Adventist school in the town of Buffalo, in the shadow of the Bighorn Mountains. Like many rural Adventist schools, it was modeled on a one-room schoolhouse, and she was its only teacher. Her life in Wyoming suited her well—the school was out in the country, and she had fewer than a dozen students, ranging in grades from first to eighth—but even as she devoted herself to the children, Claire found she could not shake her recurring thoughts about her baby. She wanted to have a child of her own, before she ran out of time, and her dreams about holding her son took on a new intensity.

Claire had sought psychological help at Tarleton with little success, and two years after moving to Wyoming, she tried again. Soon she met a bright, empathetic local therapist who listened without judgment as she described the anger that sometimes felt as if it might consume her. She began to see him in twice-weekly sessions in his comfortable office just off Main Street, where she finally spoke freely—nearly two decades after the fact—about having lost Tom and the baby. “It was the first time I’d been given permission to talk about what had happened and to mourn in any sort of meaningful, sustained way,” said Claire.

Her therapist told her about post-traumatic stress disorder, a then-new medical diagnosis that he said described the array of symptoms some trauma victims, many of them veterans of war, experienced in the wake of catastrophic violence. PTSD, he explained, was characterized by nightmares, emotional detachment, rage, and a strong desire to avoid people and places that might trigger memories of the trauma. It was a diagnosis Claire reflexively resisted, because to accept it “felt cheap, since I hadn’t earned it,” she said. “I had never seen the horrors of Vietnam.”

The incremental progress she was making was cut short when, six months into counseling, her therapist transferred her into group therapy, and Claire found herself surrounded by people with substance-abuse problems—many of whom had been mandated, by court order, to attend—who had little insight into her state of mind. At loose ends, she abandoned the group and took up with a 19-year-old ranch hand and Wyoming native named Brian James. Then 38, she had little in common with the soft-spoken high school graduate, but in him she saw a kindred spirit with a curious and unconventional mind. Each afternoon, after she had dismissed her students, they talked for hours, hiking through the canyons and dry creeks that he had grown up exploring. Eight months after they met, they decided to get married.

When they wed, in August 1986—a full twenty years after the UT tragedy—Brian was just two years older than Claire had been when she was shot. “I think she was still trying to recover all that she had lost at eighteen,” her sister, Lucy, told me. They moved to Arizona, where Lucy had already put down roots, and rented a house in Patagonia, near the border town of Nogales. Claire taught elementary school and Brian worked construction jobs, and their marriage was a happy one at first, though they would never delve into the defining event of her life. “I knew Claire had been shot, and that she had lost her boyfriend and her baby, but we never had a deep conversation about it,” Brian told me. “It wasn’t something I asked her about, and it wasn’t something she seemed eager to discuss.”

Instead, Claire tried to get pregnant, but she was met with disappointment. Though her doctors in 1966 had assured her that she would still be able to have children despite being left with one ovary and a uterus that had been stitched back together, she often wondered if Whitman, who had already robbed her of so much, had also stolen her ability to conceive.

She had all but given up by 1989, when she was 41, and her mother called with an improbable offer. Mary Wilson was by then on her third marriage and had reinvented herself as a successful New York City real estate agent. She was animated on the phone as she laid out her proposal for Claire: a realtor who worked for her, who had emigrated from Ethiopia, had introduced her to a good friend of his from Addis Ababa. The friend had been allowed into the United States a year earlier so that his young son could undergo emergency surgery for a congenital heart defect that had left him near death. The boy had remained in the States so he could receive follow-up medical care, but he and his father had overstayed their visas, and if they returned to Ethiopia, he would not have access to the pediatric cardiologists he needed.

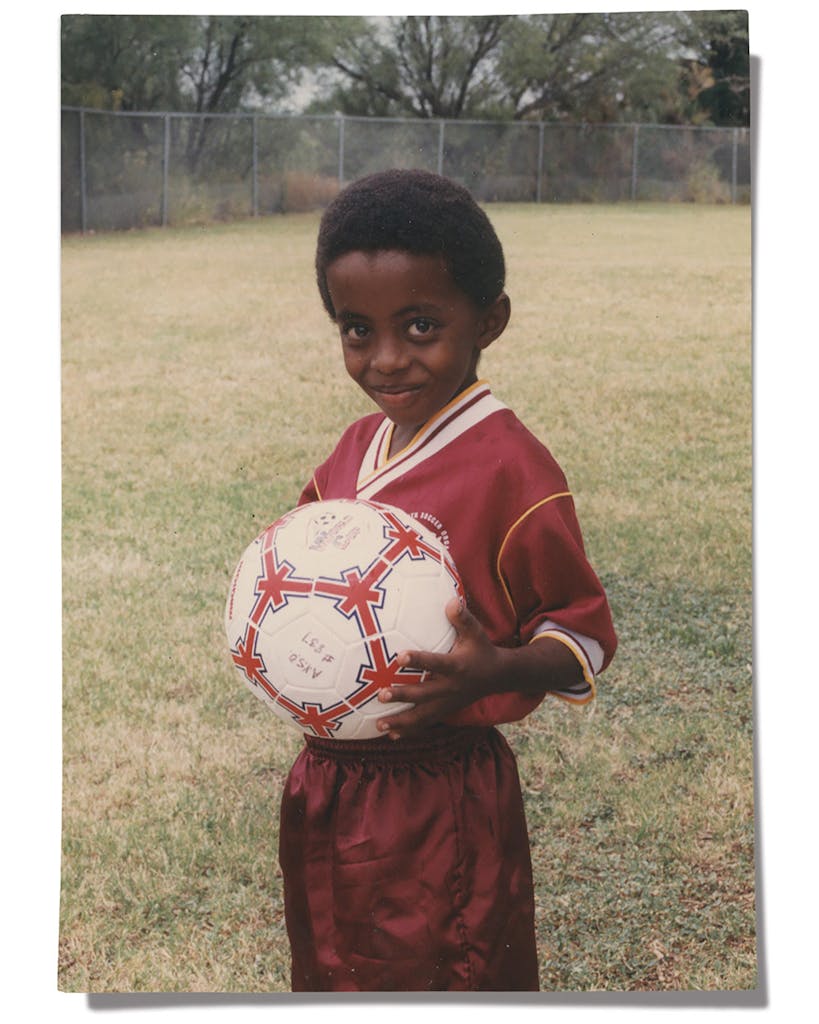

The father had already embarked on the long and complex process of seeking asylum, her mother continued, but his and his son’s legal status was precarious. Would Claire and Brian consider adopting the boy, she asked, so he could remain in the country? The first step would be to take legal guardianship of him, an effort that his father supported. The boy was four years old, added her mother, and his name was Sirak.

That June, after Claire had studied every book she could find at the library on the subject of adoption, she and Brian packed up their hatchback and embarked on a cross-country road trip to New York to meet the little boy who would become their son. “He was an incredible gift,” Claire said. “A gift I didn’t expect.”

IV.

Sirak had not seen his mother since he had left Addis Ababa as a toddler, and from the moment he caught sight of Claire in her mother’s house in Riverdale, he brightened. “I can’t remember a time when I didn’t know her,” Sirak told me. On their first day together, his father and Brian set out to go sightseeing around the city, leaving Sirak and Claire to become acquainted with each other. For the next three days, she fed him, bathed him, sang to him, read to him, and tucked him in at night. He was cheerful and playful in return, and from the first day, he called her Mommy in his accented English.

When it was finally time to load his meager belongings—two shirts, two pairs of shorts, and a toy school bus—into the hatchback and head home to Arizona, his father walked him to the car and buckled him in. “His dad was very loving, but he didn’t make a big deal out of saying goodbye,” Claire said. “He made it seem like Sirak was going on a long trip, on a big adventure.” Sirak’s father could travel inside the United States while his application for asylum was under review, and he promised the boy that he would come see him soon.

As Brian drove, Claire and Sirak sat together in the back seat, watching as the Manhattan skyline faded from view. The boy cried quietly to himself for a few minutes, but he became more animated as they moved farther from the city, and he was insistent on Claire’s undivided attention. If she pulled her book out and started to read—she was in the middle of James Michener’s Alaska—he would stick his head between her and the page, grinning. If she lay down and stretched out across the back seat, he would sprawl on top of her until his face hovered just above hers. They remained that way for hours, talking and laughing and staring up at the flat, blue summer sky.

Though they could not have looked any more different, they each bore a similar scar: a long, vertical line along the torso where a surgeon’s scalpel had once traced a path. Hers began below the sternum, while his was located higher up, closer to his heart. Years later, when he was old enough to understand, Claire would tell him what had happened to her in 1966 and he would listen, carefully considering her story, before adding that he would always think of the baby she had lost as his brother.

Despite the fact that Sirak had been born with a ventricular septal defect, or a hole in his heart, he thrived. He was a healthy, if slight, little boy, and when Claire took him to see his pediatric cardiologist every three months for his checkups, he was usually given a clean bill of health. As the only dark-skinned person in their community, he was a source of fascination to the kids who reached out to touch his hair. But Sirak embraced the very thing that set him apart, beaming when his father—who made biannual visits to Arizona—stood before his classmates and spoke about their African heritage. From the start, Sirak was quick to make friends and an exuberant presence. “Teach me!” he exhorted one teacher the summer before he started kindergarten.

Claire and Brian formally adopted him when he was six years old, shortly after they moved west to the unincorporated community of Arivaca. Sirak’s father continued to make the trek out to see them, and each time he left, the boy would take the snap-brim cap his dad had worn during his visit and bring it to bed with him, resting it on the pillow. On nights when the stars shone so brightly above their desert outpost that they illuminated the canyons below, Claire, Brian, and Sirak would roll out their sleeping bags on the flat portion of their roof and lie side by side, staring up at the constellations.

Still, the area between the two lower chambers of Sirak’s heart remained fragile, and at the age of seven, he was rushed into surgery after an echocardiogram suggested that his aorta had narrowed and was impeding blood flow to his brain. (The operation was called off after another round of tests.) Afterward, Claire found herself preoccupied with the possibility that something cataclysmic might happen. Even a nick in the mouth—sustained during a dental exam, say, or while playing with other kids—could allow bacteria into his bloodstream and have fatal consequences. Claire girded herself, carrying supplies of antibiotics in her purse at all times, but she could not shake her fear that, at any moment, she could lose Sirak. Once, she dreamed that she watched him board a bus that then abruptly pulled away, and she chased after it, calling out for the boy and waving her arms wildly, before losing sight of him.

Claire did her best to keep her worry to herself. Harder to hide was the anguish she had carried since the shooting, which would surface unpredictably despite how fortunate she felt about finally having a family. “I still had so much anger,” Claire told me. She was moody and short-tempered, often lashing out at Brian, who grew distant, spending more and more time away from home. In 1996, when Sirak was eleven, Claire accepted a teaching position at a Seventh-day Adventist school in Virginia and took their son with her. Three years later, she and Brian divorced.

And then, just like that, Claire was a single mother, scratching out a living, ashamed by her cardinal failure, as she saw it, to keep her family intact. Her restlessness ensured that she and Sirak did not stay in Virginia long; they moved to Nebraska in 1999, when he started high school, and then to Kansas two years later. Though her pay as a teacher was barely enough to get by on, she and Sirak were resourceful, baking their own bread and gathering windfall apples. In Virginia, where they lived next to a public housing project, Claire sometimes treated herself to a 25-cent copy of the Washington Post, and she and Sirak took turns reading the restaurant reviews aloud at the kitchen table, imagining that they, too, were dining in a white-tablecloth establishment.

What little Claire scraped together she put into piano lessons for her son, who was captivated by classical music. Once, when she reached to turn down the volume of a Beethoven symphony they were listening to in the car, Sirak had signaled for her to stop. “No,” he said, smiling, as if transported. “We were just getting to the exciting part.” He spent hours at the piano each day practicing Chopin’s Études, and he played wherever he could find an audience, from their church to local nursing homes.

Then one day, at age fourteen, he started complaining of blinding headaches. His physician initially believed he had meningitis, but after further testing, he was diagnosed with Guillain-Barré syndrome, a rare disorder in which the body’s immune system attacks the nervous system, often causing temporary paralysis. Sirak was rushed to the hospital, where he soon found himself unable to walk. Seeing Sirak confined to a hospital bed—so weak, at first, that he could not play the keyboard his teacher had brought him—Claire was seized by terror. As she sat vigil at his bedside, she closed her eyes and bowed her head, silently pleading with God not to take this son from her too.

The syndrome, exotic-sounding and mercurial, eventually ebbed with treatment, and Sirak returned to the ninth grade a month later, shuffling behind a walker. No sooner was his body strong again than he faced another ordeal; during his hospitalization, doctors had discovered he needed open-heart surgery to repair his aorta, this time unequivocally. The operation, performed in the spring of 2000, was a success, though it would be another three years—when his cardiologist told Claire that his heart had fully healed—before she felt any sense of relief. Sirak, who was eighteen by then, would be a healthy adult, the doctor explained.

Sometimes, in those days after Sirak’s recovery, Claire thought back to an epiphany she’d had years before, while on a hike in Wyoming. She had come across a tree whose trunk bent at a dramatic angle at its midway point, forming a curvature that resembled the letter C. Something catastrophic—lightning? drought?—had diverted it from its path, but the tree, resilient, had righted itself and grown straight again.

V.

Claire was still living in Virginia in the spring of 1999 when one word—Columbine—became synonymous with mass murder. Because she did not own a TV, she was not subjected to the disturbing footage that seemed to play on every channel, in which petrified teenagers streamed out of their suburban Denver high school, hands over their heads, frantic to escape the carnage inside. Still, when she saw the headlines, she felt her pulse race. She scoured the newspaper for details—about the pair of teenagers who had come to school armed with bombs and guns; about the 12 students and the teacher who had been slaughtered; about the 21 gunshot victims who had survived. Even as she grieved for them, Claire was taken aback by the attention the shooting commanded. As the victim of a crime that was still cloaked in silence and shame, she felt strangely envious. “So much of what had happened to me was still a mystery,” she said. “Every single detail that revealed itself was precious.”

In fact, Claire had begun to reconstruct parts of her story the previous Thanksgiving. That week, she had stopped in a bookstore in Washington Dulles International Airport, where she was waiting for a flight that would take her to Arizona to see her sister. Sirak was staying with friends for the holiday, and Claire, who was rarely apart from him, was on her own. Someone she knew had recently mentioned an item in the Washington Post on a new book called A Sniper in the Tower, by Texas historian Gary Lavergne, and Claire, who was curious to see it, eyed the shelves. Though pop culture had elevated Charles Whitman to near-mythic status in the intervening decades through both film and music—Harry Chapin’s 1972 song “Sniper” cast him as a misunderstood antihero—the tragedy itself had received scant attention, save for the obligatory anniversary stories that ran in Texas newspapers.

Claire finally spotted the book, whose cover featured an old black and white yearbook photo of Whitman wearing a wide grin. Rather than start at the beginning, she flipped to the end and scanned the index, where she was startled to see her name. Turning to the first citation, on page 141, she skimmed the text and then came to a stop. “Eighteen-year-old Claire Wilson . . . was walking with her eighteen-year-old boyfriend and roommate, Thomas F. Eckman,” she read. “Reportedly, both were members of the highly controversial Students for a Democratic Society. She was also eight months pregnant and due for a normal delivery of a baby boy in a few short weeks.”

Claire could feel her heart thumping in her chest at what came next:

Looking down on her from a fortress 231 feet above, Whitman pulled the trigger. With his four-power scope he would have clearly seen her advanced state of pregnancy. As if to define the monster he had become, he chose the youngest life as his first victim from the deck. Given his marksmanship, the magnification of the four-power scope, an unobstructed view, his elevation, and no interference from the ground, it can only be concluded that he aimed for the baby in Claire Wilson’s womb.

Claire stood still, the frenetic energy of her fellow travelers receding into the background. What astonished her more than the notion that Whitman had deliberately taken aim at her child—an idea she could not yet fully grasp—was the simple fact that what had happened to her more than three decades earlier was written down in a book that she could hold in her hands. Though she had no money to speak of at that particular moment—her father had purchased her plane ticket for her—she did not hesitate before handing over her last $20 to buy the book, which she devoured on her flight to Tucson.

The act of reclaiming her history would come afterward in fits and starts, beginning one summer night in 2001, when Claire sat at her computer and used a search engine for the very first time, carefully typing out the words “UT Tower Shooting.” She had only a dial-up connection, and the results were slow to load, but the first link that appeared led to a blog written by an Austin advertising executive named Forrest Preece, who had narrowly escaped being shot by Whitman. Preece had been standing across the street from the Student Union, outside the Rexall Drug Store, on the morning of the shooting, when a bullet had whizzed by his right ear. As Claire read his account of the massacre—“Every year, when August approaches, I start trying to forget . . . but as any rational person knows, when you try to forget something, you just end up thinking about it more”—she felt strangely comforted. Each detail he described—the earsplitting gunfire, the bodies splayed on the ground, the onlookers who stood immobilized, wild with fright—was one she had carried with her all those years too.

Claire initiated a sporadic correspondence with Preece as she continued her itinerant existence—first heading to New York, to take care of her ailing mother after Sirak left for college, and then moving back to Colorado, in 2005, and Wyoming, two years later, to teach in Adventist schools. In each place, she felt the strange pull of the shooting tug at her. Once, in a sporting goods store in the Rocky Mountains, she decided to stop at the gun counter and ask the clerk if she could look at a .30-06. (Whitman had in fact shot her with a 6 mm bolt-action rifle, but Claire had been told otherwise.) The clerk laid the .30-06 out on the glass counter and Claire studied the weapon, finally reaching out to touch its stock, before pulling her hand back a moment later, unsure what she had come to see. Another time, while driving through the Denver area, she chose to take a detour through Columbine, even circling around the high school. She could not say exactly what she had gone looking for “except for some deeper understanding,” she told me, that went unsatisfied.

Claire had stayed away from Austin for nearly forty years, but in 2008, when Preece asked her to attend a building dedication for the law enforcement officers and civilians who had helped bring Whitman’s rampage to an end, she felt compelled to return. The previous year, a student at Virginia Tech had armed himself and opened fire, killing 32 people and injuring 17, and Claire, rattled by yet another tragedy, craved human connection.

At the ceremony, which took place at a county building far from campus, she fumbled for the right words as she tried to convey her thankfulness to Houston McCoy, one of the police officers who had shot Whitman. When she later joined him, Preece, and several former officers on a visit to UT, she was dismayed to find that the only reference to the horror that had unfolded there was a small bronze plaque on the north side of the Tower. Set in a limestone boulder beside a pond, it was easy to miss. As Claire surveyed the modest memorial, an industrial air conditioning unit that sat nearby cycled on and a dull roar broke the silence. “I had heard about the memorial and had taken solace in thinking that it was a lovely place,” she told me. “I was so disappointed to find no mention of Tom, the baby, or any of the victims.”

Afterward, at his home, Preece showed her old news footage that TV cameramen had shot on the day of the tragedy, looking out onto the South Mall. As she watched, Claire was startled to realize that she was looking at a grainy image of her younger self, lying on the hot pavement. When she saw two teenagers dash out from their hiding places and run headlong toward her, she leaned closer, dumbstruck. Local news stations had aired the footage in the aftermath of the shooting and on subsequent anniversaries, but Claire had never seen any of it, and witnessing her own rescue was revelatory. She had always known the name of one of the students who saved her; James Love, a fellow freshman, had been in her anthropology class, and she had stopped him on campus once in 1967 to thank him for what he had done, but he had seemed ill at ease and eager to break free from the conversation. His partner, a teenager in a black button-down shirt and Buddy Holly glasses, had remained unknown to her, so much so that she had half wondered, until she saw the black and white footage, if he had been an angel.

Preece helped her solve the mystery in 2011, after he spotted a headline in the American-Statesman that read “Man Who’s the Life of the Party Has Brush With Death.” Below it, the article detailed how a local performance artist named Artly Snuff, a member of the parody rock band the Uranium Savages, had survived a near-fatal car accident. Born John Fox, Snuff had graduated from Austin High and been weeks away from starting his freshman year at UT when Whitman opened fire. Though the article never referenced the shooting, the mention of Snuff’s name jogged Preece’s memory, and he recalled a Statesman column on Snuff years earlier in which he was praised for having helped carry a pregnant woman in the midst of the massacre.

Preece tracked down Snuff on Facebook, and in 2012, he put him and Claire in touch. “To finally hear her voice was stunning, because I’d wondered what had happened to her so many times,” Snuff told me of their first phone call, which spanned hours. “For both of us, just talking was a catharsis. I’d seen things no seventeen-year-old should ever have to see, and I’d carried those memories with me, and Claire understood.”

Snuff told Claire how he had crouched behind the Jefferson Davis statue with Love—a friend of his from high school whose life was later cut short by bone cancer—as gunfire erupted around them. They had agonized about what to do, he explained, as they looked onto the South Mall and saw her lying there, still alive. Too terrified to move, they had initially stayed put—Snuff’s own cowardice, as he saw it, measured in fifteen-minute increments whenever the Tower’s bells chimed on the quarter hour. In a voice thick with emotion, he told her that he had always regretted taking so long to work up the courage to help her.

Claire assured him that he owed her no apologies, saying that she loved him and would always think of him as her brother. She said so again when they saw each other in Austin in 2013, wrapping her arms around him in the entrance of the Mexican restaurant where they had agreed to meet. Oblivious to everyone else, they embraced for several minutes. “It was so affirming to finally say thank you,” Claire told me.

Around them, a national debate about gun control had just erupted with new force. Three months earlier, in Newtown, Connecticut, a disturbed young man had fatally shot twenty children, none more than seven years old, and six adults, at Sandy Hook Elementary School. In a forceful speech at a memorial service for the victims, President Barack Obama had pushed for tighter regulation of firearms, warning that the cost of inaction was too great. In response, many gun owners had bristled at the notion that fewer licensed weapons, and more government regulation, would keep anyone safe. In Texas, where the Legislature was in session that spring, lawmakers had proposed several “campus carry” bills, which sought to upend the long-standing state law banning firearms at public universities. If passed, concealed handguns would be permitted on university grounds, in dorms, and in college classrooms.

Claire had returned to Austin because Jim Bryce, a lawyer and gun-control activist whom she had met when they were both students at UT, had asked if she, as a victim of campus gun violence, would testify at the Capitol. Though she had not engaged in any activism since the sixties—the Seventh-day Adventist Church advocates strict political neutrality—she felt that she could not turn down Bryce’s invitation. And so on March 14, 2013, Claire appeared before the Homeland Security and Public Safety Committee, one among scores of people who had come to voice their support or opposition to the bills. No longer the campus radical she had once been, she did not stand out in the overflow crowd; at 65, everything about her—from her chin-length silver bob to the reading glasses she slid on when it was her turn to speak to her comfortable shoes—was muted and sensible.

Like the other speakers, Claire was allotted three minutes. Compressing the totality of her experience into a few sound bites seemed impossible, but once at the microphone, she tried. “I never thought about somebody using a gun to kill themselves or others until August 1, 1966, when I was walking across the campus of the University of Texas,” she said, her voice clear and steady. She sketched out what had happened to her in a few unadorned sentences—“I was eighteen and eight months pregnant”—and when she reached the end of her story, she added, “I was not able ever again to have a child.”

She expressed her reservations, as both an educator and a sixth-generation Texan who had grown up around guns, about the proposed bills, arguing that the Legislature’s objective should be to prevent future attacks, not arm more civilians. “A campus is a sacred place,” she said. Then her time was up.

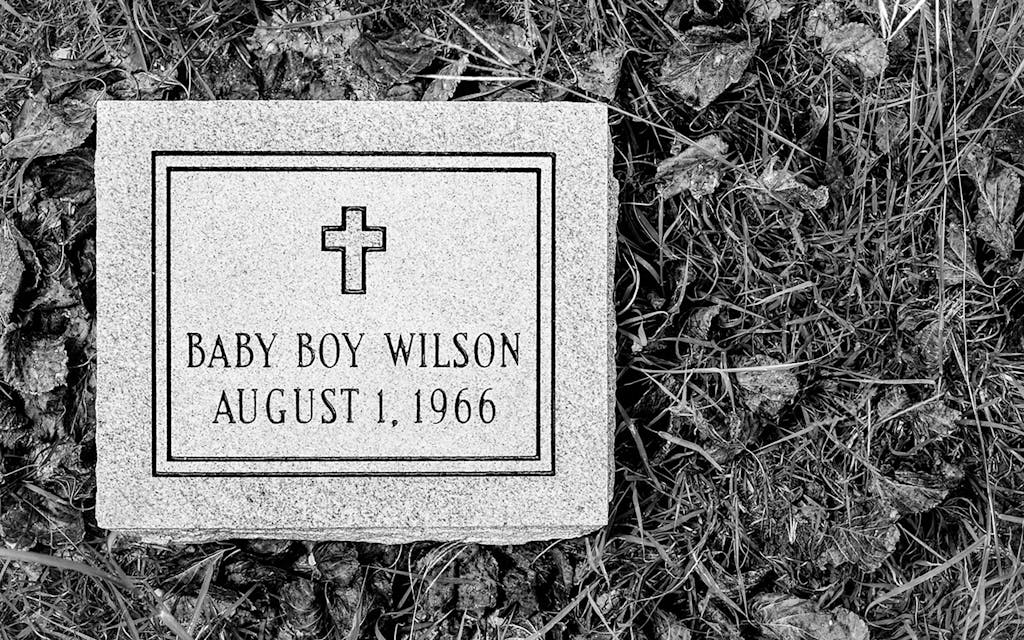

That fall, Claire received an email from Gary Lavergne, with whom she had met and corresponded after reading A Sniper in the Tower. The email told of an astounding discovery. “My Dear Friend, Claire,” it began. “A few years ago, while working on my last book, I downloaded a database of grave sites located in the Austin Memorial Park. (My purpose was to locate the graves of some of the persons I had written about in Before Brown.) It wasn’t until this past weekend that, while browsing among the almost 23,000 entries in that dataset, I noticed an entry for a ‘Baby Boy Wilson.’ ”

Lavergne went on to explain that the burial date for the child was listed as August 2, 1966—the day after the massacre. Records showed that the unmarked plot had been purchased by a Lyman Jones, a man whose name Lavergne did not recognize. Claire did, immediately; a veteran journalist who had written for the Texas Observer during the fifties and sixties, Jones was her mother’s second husband, and Claire’s stepfather, at the time of the shooting.

Claire had always been aware that the baby had received a proper burial, but she had not pressed her mother for details until her later years, when her mother’s memory was failing and she could no longer summon them. The small plot, she now learned from Lavergne, was located in a section of the cemetery mostly devoted to infants and stillborn babies. “Claire, I hope this gives you comfort,” he wrote, explaining that he had gone to Austin Memorial Park to find the burial place. “Attached is a picture I took of the grave site. Your son is buried beneath the flowers I placed there so that you can see the exact spot.”

Claire read and reread the email in silence, brushing away tears. Your son. Buried beneath the flowers.

She would visit the cemetery the following August, after Lavergne and his family had a headstone made, with Claire’s blessing. Below the image of a cross, it read:

Baby Boy Wilson

August 1, 1966

It stood near the perimeter of the cemetery, on a sunburned stretch of grass near a single hackberry tree. When Claire found it, she knelt down and gathered a handful of soil, placing it inside a folded sheet of paper, for a keepsake. Then she prostrated herself, pressing her forehead against the marble marker, which was cool even in the blazing August sun. She thought about Tom and about the baby’s father, John Muir, whom she had called and spoken with, after a decades-long estrangement, before he had passed away that June. As she lay there, she was acutely aware of the baby’s presence, of the molecules somewhere below the earth’s surface that belonged to him. Claire stayed for a long time and prayed. “I felt not so hollow,” she said. “I felt close to God.”

VI.

Claire lives in Texas now, having finally, after all her years of wandering, come home. Six years ago, she moved to Texarkana—which, with some 37,000 residents, is the most densely populated place she has lived for some time. An Adventist school had needed a teacher, and so, as she had done more than a dozen times before, she started over. Not since Eden Valley has she remained in one place for so long.

When I went to visit her earlier this year, we met at her white double-wide trailer, which sits on the pine-studded, western edge of town. Her bedroom window looks out onto a pasture, and though the view lacks the grandeur of the Rockies or the Great Plains, it allows her to imagine that she still lives in the wilderness, far from civilization. A few steps from her front door, in raised beds she built herself with wood, she had planted a winter garden. Collard greens and kale flourished next to fat heads of cabbage, and despite a recent freeze, a few stalwart strawberry plants thrived. As we talked, Claire bent down and tore off a few sprigs of mint, handing me some to taste. “Isn’t it wonderful?” she said, her pale blue eyes widening.

When Claire told friends about her life in Texarkana, she focused on the happy things: her garden; the Nigerian family she had befriended; her students, many of whom lived below the poverty line, who hugged her waist and called her Miss Claire. She did not share her worry about Sirak, who was standing beside her on that January morning. He wore a cheerless expression, a black wool hat pulled down to his eyebrows, his shoulders squared against the cold. He had moved back in with her in August, not long after his thirtieth birthday, but he bore little resemblance to the young man she had sent off to college. Unless prodded to talk, he said little, and his speech was slow and leaden. Every now and then, as Claire and I chatted, he would smile at the mention of a childhood friend or a story about his and Claire’s days in the Arizona high desert. Except for those moments, he seemed to have taken up residence in a world of his own.

For Claire, the first clue that something was not right with Sirak came in 2007. Then a month shy of graduating with a music degree from Union College, in Nebraska, Sirak had called her late one night. “Mom, my thoughts are racing and I can’t make them stop,” he confided, adding that he had not been sleeping much. Claire offered reassurance, certain these were the typical jitters of a graduating senior. But that July, shortly before he was set to begin a prestigious teaching fellowship in the University of Nebraska’s music program, he called again and begged her to take him home. Rather than try to reason with him, she made the ten-hour drive from Colorado. When she arrived, she found Sirak standing in the parking lot of his apartment complex, wide-eyed and on edge. He refused to step foot inside his apartment by himself. “He was terrified, shaking, talking so fast,” she told me. “That’s when I knew something was really wrong.”

At home, his behavior only grew more erratic. Sirak, usually a modest person, would walk to the mailbox at the end of their driveway in nothing but his underwear. He slept little and was reluctant to venture far from the house. Once, after he and Claire ate out, he told her he was sure that the restaurant’s staff had put laxatives in their food. She took Sirak to see a series of mental health professionals, but no one could offer a definitive diagnosis; a prescription for Lexapro, a popular antidepressant, did little to lessen his anxiety. Sometimes he would slip into a manic state, and Claire would coax him into her car and head for the emergency room. “At the hospital, I always got the same question: ‘Is he threatening you or trying to hurt himself?’ ” she said. “And I would say, ‘No,’ and they would tell me that they couldn’t help me.”

Rather than face his descent into mental illness alone, Claire reached out to his biological father, who had been granted asylum in 1999. (Her ex-husband, Brian, had remarried and largely receded from Sirak’s life.) The rest of Sirak’s family—his mother, two brothers, and two sisters—had immigrated when Sirak was thirteen and settled with his father in Atlanta. Sirak had visited them nearly every summer since, and he and his siblings had forged an easy bond. Claire believed that Atlanta, with its big-city mental health resources, would be a better place for him than rural Colorado, and in 2008, it was agreed that he would go live with his Ethiopian family.

In Atlanta, a psychiatrist finally diagnosed Sirak with bipolar disorder and prescribed him lithium, a mood stabilizer. During long, discursive phone conversations with Claire, Sirak assured her that he was taking his medication, but despite his sincere longing to get well, he never consistently followed his treatment protocol. Though he managed to hold a number of menial jobs—he bagged groceries, worked as a drugstore clerk, cleaned out moving trucks, delivered auto parts—his employment was often cut short when a manic episode overtook him. By 2012, during one of many voluntary commitments to Georgia Regional, a large, state-run hospital with a psychiatric ward, his diagnosis was modified to reflect his worsening condition. “I have Bipolar One, manic severe, with psychotic features,” Sirak explained to me matter-of-factly, referring to the most severe form of the disorder.

When Claire saw Sirak on a visit last July, she was stunned. His doctors had put him on a powerful antipsychotic drug to keep his most serious symptoms in check, but it was plain that he was overmedicated. Sirak absently raised his feet, walking in place where he stood, and looked unfocused, his clothes rumpled, his hair uncombed. When he sat, he sometimes drifted off to sleep, and when he spoke, his voice was a curious monotone. “I’m not enjoying being alive very much right now,” he told her. Eager to find a way to dial back his medications, she moved him to Texarkana the following month and gave him her spare bedroom. She found a psychiatrist to fine-tune his prescriptions and arranged for weekly talk therapy sessions. The change of scenery seemed to help him, at least at first. “Today Sirak told me he no longer wants to die,” Claire emailed a handful of close friends in late August. “Rejoice with me.”

By the time of my visit, he had lapsed back into a depression, and he announced that he wanted to return to Atlanta. (Several weeks later, he did.) Though he had once devoted hours each day to the piano—in 2012 he even went to New York to audition for the master’s program at Juilliard—he had stopped playing, he told me, because he had lost his passion for music. “My doctor said I have something called anhedonia,” he said. “It’s like hedonism, but the opposite. It means I don’t feel pleasure anymore.”

He brightened only when he changed the subject to an obsession of his: his conviction that he will one day be reborn as a “child of prophecy,” or a sort of modern-day messiah. As he described the superpowers he would possess when the prophecy came to fruition, he grew elated, his face alight. Beside him, Claire sat in silence, staring down at her clasped hands.

What if Whitman’s bullet had never found her? Claire sometimes thinks about the intricate calculus that put her in his sights that day. What if her anthropology class had not let out early? What if Tom had lingered over his coffee one minute longer before they had gone to feed the parking meter? Such deliberations have never satisfied her, because each shift in the variables sets in motion other consequences. If she had not been shot, she might never have found God. If she had given birth, she would not have known the exhilaration, at 41, of becoming a mother, or the hard-won joy of raising Sirak. Sometimes she finds herself calculating the age of her first child, had he lived, and the number always astonishes her. She wrote it in my notebook one afternoon, carefully forming each numeral: 49. He would probably be a father by now, she observed, and she a grandmother.

She rarely gives much thought to Whitman, who remains, in her mind, remote and inscrutable. “I never saw his face, because we were separated by so much distance,” Claire said. “So it’s always been hard to understand that he did this—that a person did this—to me.” Paging through Life on her library visits all those years ago, she studied the photos of him, and one particular image—taken at the beach when Whitman was two years old—has always stayed with her. In the picture, he is standing barefoot in the sand, grinning sweetly at a small dog. Two of his father’s rifles are positioned upright on either side of him, and Whitman is holding on to them the way a skier grips his poles.

“That’s how I see him—as that little boy on the shore, still open to the world, just wanting his father’s love and approval,” Claire said. She cannot grasp how, in such a short span of time, “he became so twisted and decided to do what he did,” she said. “But I’ve never felt it was personal. How could I? He didn’t know me, I didn’t know him.”

It will have been fifty years since the shooting this summer, an anniversary that, for Claire, has brought the tragedy into clearer focus. A documentary that tells the story of the day of the massacre from the perspective of eyewitnesses and survivors, with an emphasis on Claire’s ordeal, premiered at the South by Southwest Film Festival in Austin in March; directed by Austin-based filmmaker Keith Maitland, Tower will air nationally on PBS later this year. (The documentary is loosely based on a 2006 Texas Monthly oral history; I served as one of its executive producers.) The film, and recent efforts to plan a memorial for August 1, have reconnected Claire to people she thought she would never see again. “I felt so isolated by the years of silence,” she wrote to Maitland during filming. “Now I feel restored to the community from which I was ripped.”

Last spring, Claire found herself at the Capitol once again to testify against legislation that would allow concealed handguns on college campuses. While the bills she opposed in 2013 had ultimately failed, this time her testimony did little to deter gun-rights advocates, who succeeded in passing a campus carry bill by a two-to-one margin. Though supporters argued that the measure would make universities safer, Claire was heartened when protests erupted at UT, where an overwhelming majority of students, professors, and administrators balked at the Legislature’s actions. In what Claire sees as a grotesque insult, the law will go into effect on August 1, half a century to the day that Whitman walked onto the Tower’s observation deck and opened fire.

Like many survivors of the shooting, Claire will return to campus to mark the anniversary. The university, now a sprawling, multibillion-dollar institution whose shiny new research facilities dominate the landscape, is drastically different from the one she entered in 1966, but the unsettled legacy of that summer remains. Though the gaping bullet holes left by Whitman’s rampage were quickly patched over, not every scar was filled, and anyone who takes the time to look closely at the limestone walls and balustrades that line the South Mall can still make out tiny divots where his bullets missed their mark.

Claire longs to lie down, in the shadow of the Tower, on the precise spot where she was shot. “It’s beyond me why I would feel comforted there,” she told me. “But I want to lie down, and remember the heat, and remember Tom, and remember the baby.” That wide-open stretch of concrete is the last place they were all together.