The Wimberley fire chief pulled on his tactical boots and stepped out into the rain. He climbed into his pickup truck and drove down a bluff, toward the river.

Chief Carroll Czichos could have found his way there blindfolded. He was 62, with blue eyes and gray hair, and had lived along the Blanco River all his life. He knew its rhythms well enough to predict with surprising accuracy when the river would rise. The Blanco, after all, ran right through Texas’s “Flash Flood Alley,” one of the most notorious floodplains in the country.

Czichos steered his red Ford pickup onto River Road, a scenic panorama of turquoise water that curved for 87 miles through the Wimberley Valley, its banks sloping upward into tiers of milky limestone cliffs. As Czichos looked at the Blanco at five p.m., it appeared as it did most days—shallow, gentle, and calm. But he knew that when enough rain fell, the river could turn monstrous.

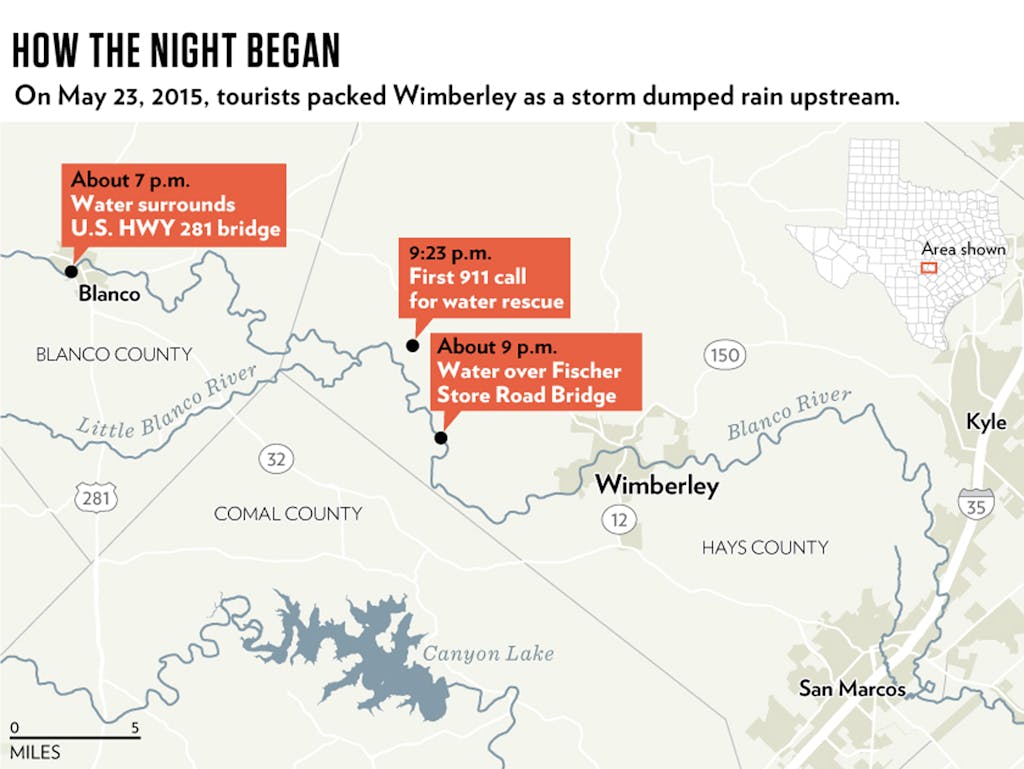

From the cab of his truck, Czichos’s eyes moved across the valley, scanning tin-roof cottages and million-dollar homes, some perched high on the hills, some low along the banks, all flirting from various distances with the river. Nearly every home and resort was packed. It was May 23, 2015, the Saturday of Memorial Day weekend, the kickoff to tourist season.

For Czichos, protecting Wimberley’s 2,600 year-round residents was one thing. But virtually overnight each spring, the town’s population tripled. These vacationers did not know the river’s savage unpredictability.

As storm clouds gathered, Czichos knew the river would rise. But he didn’t know by how much. For years he had been asking local politicians and federal and state agencies to install more gauges on the river, to tell him how much water was coming into Wimberley. But still there were no gauges upstream. Instead Czichos relied on a network of old-timers—local ranchers and property owners—to tell him what was coming. Today they had been calling his cell phone one after another, their voices urgent. The river was crawling up their tree trunks, cresting over bridges, rising higher than they had ever seen.

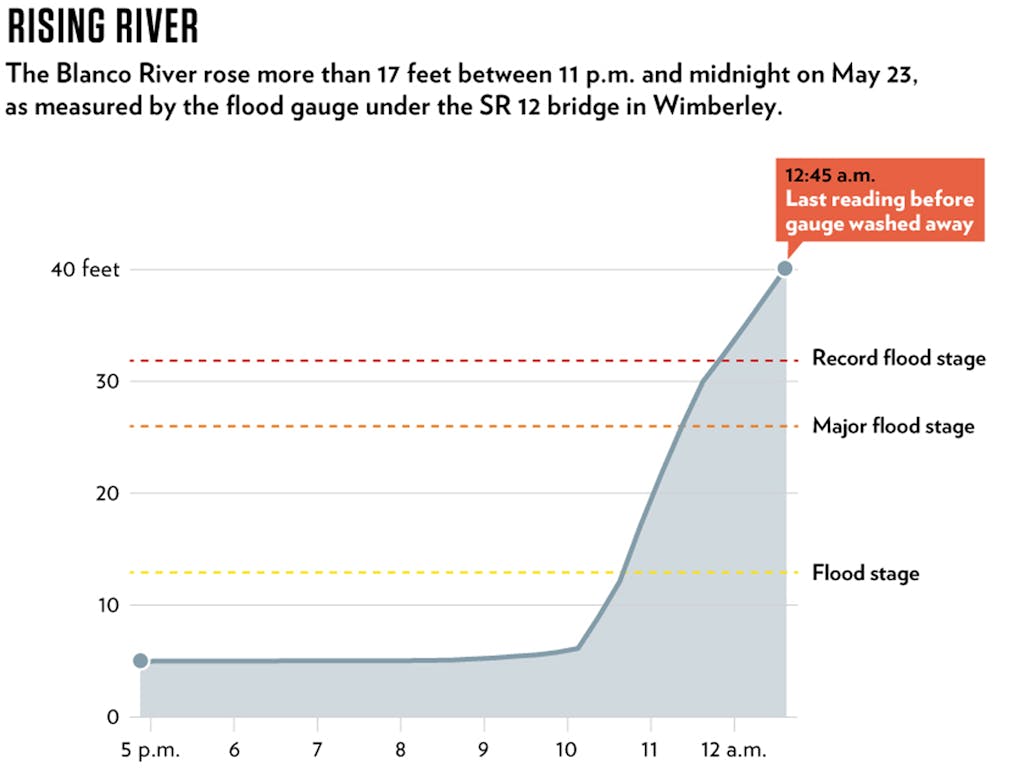

The old-timers guessed about six inches of rain had fallen upstream. The true amount, records would later show, was closer to thirteen inches, enough to transform the river into a forty-foot wall of water and create one of the worst flash floods to hit Central Texas in a generation.

Based on the phone calls Czichos fielded early that evening, he estimated the rising waters would reach Wimberley around nine p.m. He had four hours.

He headed toward the firehouse, making a mental list: call the city administrator, set up an emergency shelter, prepare the rescue boats, summon every firefighter. As he walked into the station, the rain began falling harder.

The Vacation House

Jonathan McComb, tall and lanky with hazel eyes and chestnut-brown hair, stood on the riverbank in American flag swim trunks, watching his two children—six-year-old Andrew and four-year-old Leighton—splash in the water, their bare feet sending pebbles and sand into the air.

The 36-year-old father, who helped run his family’s moving company in Corpus Christi, was celebrating his tenth wedding anniversary with his wife, Laura. The couple had considered going to Mexico but decided instead on a quick trip north to the river. The breezy slopes of Wimberley would be a respite from the hot, flat plains of South Texas, and they could join their best friends, Randy and Michelle Charba, at the vacation house owned by Michelle’s parents, Ralph and Sue Carey. Plus, Randy and Michelle had their own six-year-old son, Will.

Everyone had arrived that Friday and unpacked in the Careys’ large, orange A-frame home, with floor-to-ceiling windows and a large porch filled with chairs. The house could accommodate all nine of them.

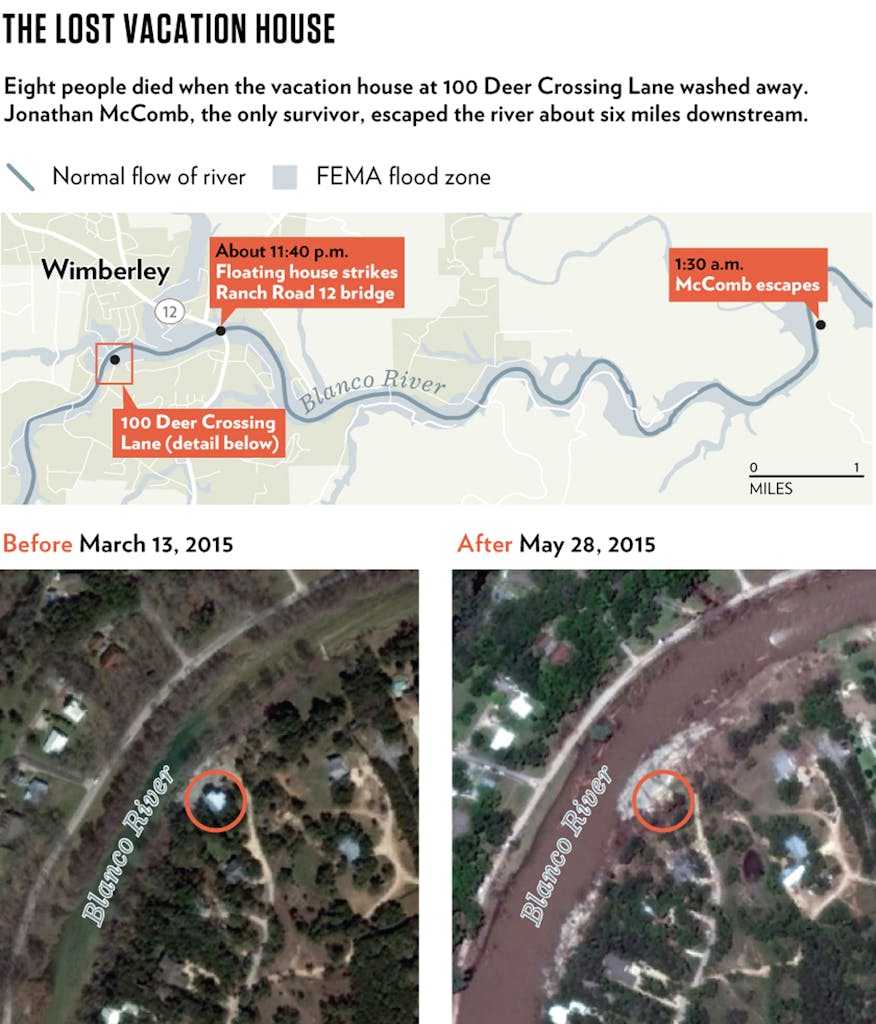

Many homes on the river were hidden in the hills, tucked behind the sprawling branches of cypress trees. But the Careys’ house stood atop a section of limestone bedrock, about 75 yards from the water, leaning closer than any other nearby homes. Because it was so visible from the river, everyone in town knew the orange house.

That afternoon, Willie Nelson songs played on outdoor speakers as brisket, chicken, and sausage smoked on the grill. The grownups took turns mixing drinks in the blender, and the women sunbathed in swimsuits on the rocks.

Randy helped the three kids into black inner tubes and pushed them into the river’s gentle current. Jonathan caught them downstream, and the kids would race up the bank to begin again. Later the two boys, Andrew and Will, discovered a water snake trapped in a pool between two boulders and spent hours running back and forth, checking to see if it had escaped. When it was time to eat, the dads carried the slippery kids up the riverbank, and Laura snapped pictures on her camera. “It was just an unbelievably perfect day,” Jonathan would say later.

About three p.m., the sky turned gray, and rain started falling. Ralph, a retired dentist, surveyed the water. He’d had the home built in the early eighties, before maps drawn a decade later put it squarely in the floodplain, before the county would have required its eight-foot concrete pillars elevate the structure twice that amount. Water had circled the house at least half a dozen times, but flooding had never been severe—nothing a couple hours with a wet vac couldn’t fix.

As the rain began to fall, Ralph did not seem worried. He suggested only that the men move their cars up the driveway to higher ground.

The city began calling numbers registered with Wimberley’s emergency notification system at 6:40 p.m. “Residents living along the Blanco should be prepared to move to higher ground and act quickly to protect your life if necessary,” the recording said. Ralph’s landline telephone at the vacation house was registered, but the first call to that number reached an answering machine, records show.

The families knew storms were building across the area, but no one inside the house was aware of their severity. They gathered in the kitchen, the children laughing, the blender whirring, as night fell outside.

The Weatherman

Forecaster Mark Lenz had already worked an eight-hour shift at the National Weather Service Forecast Office for Austin/San Antonio by the time the weather began to worsen. He sat at a bay of computers, watching as the radar images filled with red swirls of nascent thunderstorms. Lenz’s shift ended at three p.m., but he agreed to work late. The room was packed; supervisors had called in every available forecaster.

It already had been a sopping-wet May, with record rainfall across Texas. The rivers were full, the ground drenched. Even a small amount of rain would push the rivers over their banks. The fact that it was a holiday weekend—with thousands of tourists gathered along the state’s rivers—added an extra sense of urgency inside the forecast center.

It was a well-known scenario for the Hill Country: warm, moist air sweeps in off the Gulf of Mexico, then rises as it hits the hills. When the Gulf’s warm air collides with the cool air above, intense thunderstorms form. That day, the air was so wet that the storms could unleash tremendous water. “Rain bombs,” meteorologists call them. Because of the hilly topography and steering winds, storms can form over and over in the same spots. Meteorologists call this “training,” as if storms are following a train track. Whatever towns lie along the tracks get soaked.

Other factors make the region vulnerable to flash floods. Sloping hills mean the water rushes into a web of rivers. And the hills are made of limestone, not soil. Soil acts as a sponge, soaking up water. But the rock sends the water sluicing off in sheets.

For forecasters, predicting flash flooding isn’t like working hurricanes, which shift and swell for weeks before landfall. Flash flood thunderstorms form dangerously fast, usually over a matter of hours.

There’s also precious little information to determine just how an area will be affected. Computer models are good at general predictions over a broad area, but when they focus on small watersheds, like the Blanco River, the models fall apart. And without numerous river-level gauges, forecasters have not been able to build a historical record of how these watersheds behave. Forecasters have scant precise, real-time information about how much rain has fallen and how fast the river is rising.

As night fell, the weather service issued one warning after another. Lenz and his fellow forecasters tended to put large swaths of their 33-county area under flash flood watch, trying to warn as many people as possible. They risked “crying wolf” but felt they had little choice.

Lenz had grown up in Central Texas and had visited many of the small river towns under his watch. He could picture all the families, camping out, swimming, and grilling. He pulled out his plastic lunch container and bit into a turkey sandwich. It was going to be a long night.

The Preparations

Inside a big metal building on the edge of town, Czichos turned the Wimberley Central Fire Station into a command post. He dialed hotels and bed-and-breakfasts, urging owners to evacuate guests. Czichos’s family owned one of the biggest resorts, 7A, which was packed with three hundred people in cabins along the Blanco. He called his brother-in-law, who managed the property, and told him to move the visitors to higher ground.

A dozen volunteer firefighters arrived at the station in shorts and tennis shoes, and collected their dry suits, life jackets, and helmets with flashlights. They pushed the station’s ping-pong table to the side and unfolded tables and chairs, setting up workstations. They pinned a large map of the fire district, about 135 square miles, onto a white board and gathered dry-erase markers to record every incoming 911 call.

As Czichos monitored the radar on his computer, he noticed two dots of rain stalled west of Wimberley. The dots sat there for an hour or two, not moving. One dot hung over the Blanco River, the other over the Little Blanco River. Those waterways converged about ten miles west of Wimberley, joining forces before flowing through town. Typically one river flooded, or the other. But both?

Around seven p.m., Michael Klepac, one of the chief’s regular river watchers, called with panic in his voice. About thirty miles west of Wimberley, the river was quickly approaching the U.S. 281 bridge. In his 56 years of living there, Klepac had never seen it that high. “You better get people out of there,” Klepac said. The chief checked his cell phone and watched a video from Klepac, of water rushing into treetops around the bridge.

Czichos paced the station, anxious and quiet. He had grown up along the Blanco, and its rhythms and sounds were such a part of his life that when he went to fire conventions in big cities, he needed the hum of a fan to sleep. He had been the fire chief for 35 years and handled floods every year.

But on this Saturday evening, he couldn’t get his feeling quite right. What was the Blanco about to do? His calculus had never faced these particular variables. “My stomach is all churned up,” he told firefighters. “I’ve got a bad feeling.”

The First Rescue

“Chief, are you seeing this?” asked Lynn Burttschell, calling Czichos from his desk at the Texas Division of Emergency Management, in Austin. The state had mobilized too, bracing for storms across the region. Burttschell was in charge of dispatching Black Hawk helicopters and boat rescue crews to towns in the storm’s path. His team had turned its attention to Wimberley.

Burttschell, 46, worked in Austin but lived in Wimberley with his wife, preferring to raise their daughter in a small town. He had met Czichos twenty years back at the local Pizza Hut and liked him immediately. To him, the chief seemed straight off the set of Smokey and the Bandit, wearing a ball cap and cowboy boots, saying things like, “Dagummit.” Burttschell had signed up to volunteer at the chief’s firehouse years earlier.

After his shift ended in Austin, Burttschell drove the 45 miles southwest to Wimberley to help Czichos at the station. When he arrived, Burttschell stripped off his khakis and put on a dry suit. About that time, around 9:30 p.m., the switchboard at the dispatch center lit up.

“Hays County 911. Do you need police, fire, or EMS?”

“Yes, I’m at the end of Sandy Point Road and Burnett Ranch in Wimberley. And there’s a house that the river is going up into. It’s up on stilts, and there’s someone in that house.”

The dispatcher took down the details. The fire department was on the way, she said.

“Well, they better hurry,” the caller said.

Burttschell got the address and pointed his Tahoe west, where the Blanco first flowed into the county. He gripped the steering wheel as wind and rain whipped the truck. Burttschell and another firefighter launched one of the town’s three rescue boats into the water and headed toward the house.

It was pitch-black—no moon above, and the storm had knocked out power across town. The men wore helmets with flashlights that barely cut through the rain and fog. Every time lightning cracked, they looked around to get their bearings. They spotted a woman standing on her second-story porch, flashing a light.

The men pulled up beside the house, told the woman to climb aboard. She hesitated. She had a dog—could she bring him along? They nodded, and she ducked inside to get her seventy-pound poodle. After handing over the dog, she told them she also had a cat and a cockatoo—could she bring them too?

Burttschell felt a flash of impatience as large waves rocked the boat. His phone beeped nonstop with rescue calls backing up. He took his hand off the tiller in frustration, thinking, Hurry up, lady! We’ve got to go!

About that time, one of the chief’s lieutenants, who had responded to another call in the same area, radioed into the station.

“The river is over the Fischer Store Bridge,” Lieutenant Keith Tomlin said.

Everyone in the station got quiet. “Please repeat,” a firefighter said.

“Eyes on,” Tomlin said. “The river is over the Fischer Store bridge.”

Firefighters looked at one another in silence, absorbing the news. They all knew that bridge—they had driven over it, floated under it. It was a high concrete bridge that normally arched about thirty feet over the river. It wasn’t until that moment that they began to comprehend what was happening to Wimberley.

The chief quickly dialed the city administrator’s cell. “Put out another evacuation notice,” he said, his voice grave. “I don’t care what language you use. But you need to tell everybody to get the hell out. Now!”

The Calls

By ten p.m. the rescue calls were pouring into the dispatch center.

“There’s a car in the creek.”

“We are in the river—we are stuck in a tree right now.”

“We need some helicopters out here. Hurry up!”

The floodwaters rushed through town, surrounding people as they left dinner, drove home from work, watched the Houston Rockets in their living rooms. Dispatchers fielded calls from a mother stranded with her three children on a dark road, a wedding party trapped in a limousine.

A man dialed 911 from his cell at 9:54 p.m.

“We are stuck in the vehicle. We’re in the river. I think we’re being held by a tree or something.”

The dispatcher probed for details. What color car? It was a black Jeep Cherokee.

“Listen carefully. You’re in a very dangerous situation,” the dispatcher said. “Is anyone injured?”

“No. But we are inside the river. There is water getting inside the Jeep,” the man said.

“There’s water in the Jeep?”

“Yes,” the man said. His voice was calm, but a woman sobbed in the background.

“Stay calm, okay?” the dispatcher said. “Have you unhooked seat belts and unlocked the doors?”

While the dispatcher talked the man though an escape plan, she sent details of the calls to the Wimberley firehouse. As each call came in, an alarm tone sounded over the station’s intercom. Firefighters wrote the information—location, situation, number of people involved—on the white board, and the chief assigned crews. They tracked the calls on the map, seeing them snake along the path of the Blanco, heading toward Wimberley.

Rescuers made it to the Jeep and pulled the man and woman to safety. They moved on to the next call, then the next.

“The water is coming up really fast. Our cars have floated away.”

“I’ve got a deaf couple that’s trapped in the upstairs of a house.”

“You should have been here an hour or two hours ago. Get someone out here with a helicopter.”

The white board was filling up.

Chief Czichos was overwhelmed and undermanned. He still had only about a dozen volunteer firefighters on duty. He radioed other agencies for backup. But as the river roared east, his city became an island. Roads and bridges disappeared under the river’s muddy roils. Firefighters raced to call after call, only to find that they couldn’t cross the churning water to rescue people.

The weaknesses in their operation quickly became clear. Their radios could not communicate well with more-sophisticated equipment used by other agencies—they wasted precious time trying to sync channels. The chief lost track of which boat teams were where—dangerous for firefighters who might need backup, and inefficient for people waiting for help. As the calls poured in, the rescue operation became more chaotic.

Burttschell’s team chugged through the water on their rescue boat, ducking beneath power lines, struggling to figure out where they were—many street signs had disappeared beneath the water. Earsplitting cracks filled the air as huge cypress trees tumbled over, wrenched loose by the rushing water. The river transformed into a dangerous obstacle course of logs, lawn mowers, gas cans, everything from everyone’s garages, hurtling downstream. Silver propane tanks shot across the water like battering rams, hissing out smoke. The air smelled of gas and burned electrical wires. The firefighters’ cell phones kept dropping calls as they lost touch with the command center.

Burttschell felt as if he were starring in a bad Liam Neeson movie. There’s no way this is real, he thought. The black night flashed eerily as lightning split the sky. Between the rumbles of thunder, firefighters could hear screams. People, hanging off porches, standing on roofs, begging for help.

Burttschell focused on a three-story terraced house on the Blanco. The river crashed into it with such force that he could hear its backside breaking apart—glass smashing, two-by-fours snapping. The four people inside kept calling 911, pleading.

The boat wouldn’t make it, Burttschell thought. He and two firefighters jumped into the water and swam toward the house, going from tree to tree. They made it a couple yards before Burttschell had the thought: I’m about to be the dog that caught the car. If he got to the house, then what? How would he get the people to shore? He and the firefighters swam back to the bank.

Burttschell called the people on their cell. He needed to prepare them in case the house gave way. Take off your shoes, loosen your clothes, he told them. Find something to float on. They had a mattress? Good. Take off the bed linens and point it downstream. “You’re about to go for a swim.”

While he talked on the phone, another team arrived. Together, they could pull off the rescue, Burttschell thought.

The firefighters steered toward the house. The boat lurched from tree to tree, dodging logs, swinging wildly. As they drew closer, Burttschell could see the house shaking. The river was ripping it apart.

If the house gave way on top of the rescuers, Burttschell thought, no one was coming to save them. No one even knew exactly where they were. His mind flashed on his wife and nine-year-old daughter and his last words to them: “I’ll see you in the morning.”

Burttschell had been in some of the toughest water rescues of the past two decades. Katrina. Hurricane Ike. Tropical Storm Allison. In his gear, surrounded by teams of muscled men, he had never felt afraid. Maybe it was stupidity, or arrogance, but he could not remember, even once, thinking: Stop. Turn back. We’re at our limit.

He felt that now. A cold, deep rush of fear. Not just for the people on the river. But for his own team. For himself. Anyone on that violent water, for any amount of time, was not going to survive.

The boat made it to the house. The four people jumped aboard, and firefighters steered away and back to shore. They unloaded the passengers and trailered the boat.

As Burttschell returned to the firehouse, his phone beeped nonstop with addresses of incoming 911 calls. Every beep felt like someone screaming, “Help me!” Burttschell didn’t turn back.

The Evacuations

As the night wore on, residents across the valley were awakened by the noise—cracking and popping, crunching and groaning. One man thought his toilet had overflowed; another thought a pipe under the kitchen sink had burst.

Cathy Cunningham, a seventy-year-old who had lived on the river for 27 years, saw water pouring through the dog door. “I can’t get the dog door closed,” she yelled to her friend. He came over and opened the back door, and water gushed into the house. Her refrigerator suddenly flipped horizontal, and the power flickered. A bottle of gin toppled off a shelf; she grabbed it and slogged outside in waist-deep water.

Across the hills, neighbors ran from door to door shouting, “The water’s coming!” People grabbed their iPhones and iPads, their dogs and cats, photo albums and car keys, and raced into the dark. Many of their cars already were flooded. Horns honked, trunks popped open, and headlights glowed underwater as electrical systems short-circuited. One man’s garage door kept going up and down.

People encountered one another as they clambered up into the hills. One group rescued a fawn from the river, carrying it with them.

Rachel Krotzer, 41, and her husband, Mark, raced around a cul-de-sac in the Cedar Oak Mesa neighborhood, urging neighbors to leave. When a ninety-year-old woman refused, they manhandled her out of the house. “Just leave me here,” the woman cried as she waded through the water in her nightgown.

Rachel stood with neighbors watching as one house floated away, then another, and another. They began shouting at the river in the dark: “You can stop now. Please, stop!”

The Vacation House

Downstream, inside the orange vacation house, everyone had gone to sleep, except for the two young dads, Jonathan McComb and Randy Charba. They remained unaware of what was approaching.

Jonathan, still in his American flag swim trunks, sat with his friend outside, talking about hunting. Around eleven p.m., he noticed the sound.

“Man, do you hear that river? It’s roaring,” Jonathan said. He switched on a flashlight and pointed it toward the river. The water still appeared to be inside the banks, but was rising.

The men got up to put the kayaks and tubes on a ledge in the basement. Jonathan had already moved his wife’s car to higher ground but decided to move his truck too. By the time he walked back down the driveway, a foot of water had seeped into the basement.

“We might need to get out of here,” Jonathan said. He was alarmed by how quickly the water was rising. He and Randy went inside and woke the adults, to discuss whether they should leave. But the water already was so high that the men weren’t sure they could get back up the hill to their cars.

Laura McComb walked downstairs in a T-shirt and pajama pants and stepped onto the porch. She saw that water was circling the first-floor stairs—the house had three stories—and rising.

In most situations, Laura tended to take charge. She was a top pharmaceuticals sales rep at Lilly. But when she didn’t know what to do, she called her older sister, Julie Shields, who lived in Austin and was an adviser to Texas governor Greg Abbott.

Julie’s phone rang a little after eleven p.m.

“What should I do?” Laura asked her sister, telling Julie that she thought they should stay in the house. It sounded to Julie as though Laura were trying to convince herself it was the right decision.

“Call 911,” Julie said.

At 11:11 p.m., Laura placed her first call to dispatchers.

“Hi, we are—I’m not sure where we’re located. We’re on the Blanco, we’re in Wimberley, and the water is up to the second story into the house.”

“Okay, what’s your address?” the dispatcher said.

Laura asked the group for the address, then told the dispatcher, “100 Deer Crossing.” Her voice was calm, matter-of-fact.

“And you said it’s in your second floor?”

“It’s coming up to the second floor. I mean, it’s so high up,” Laura said. “And we have no exit out of the house.”

“Don’t go into the attic, because I don’t want you to get stuck there, okay?”

“Okay.”

“But I will get them out there as soon as I can,” the dispatcher said.

“Okay, thank you,” Laura said.

She hung up and called her sister again. She said crews were coming to get them. She didn’t know whether to wake the children—she didn’t want to scare them. Let them sleep, Julie told her.

Then Laura saw waves of muddy water crashing into the porch stairs, like a tide. Suddenly eight feet of water surrounded the house on all sides.

“Oh my god, oh my god,” Laura said. “I’m going to throw up.”

After the second call to Julie, the families woke the children and gathered in the living room on the second floor. The moms, Laura and Michelle, tried to console the kids. “It’s okay,” they said. “The river’s coming up, but it’s going to be okay.” Water slammed into the floor-to-ceiling windows and began seeping into the house.

The dads searched for a way out. Jonathan picked up a chair and broke out a back window. He saw a tree branch outside. Could he get a rope to the tree and have everyone slide out?

He stepped out onto the air-conditioner unit to look around. “Get off that, it’s fixing to go!” Randy shouted. Jonathan ducked back into the house, just before the rushing waters ripped off the unit and carried it away.

Then they heard a thunderous crack, and the house trembled. A cypress tree must have crashed into the house, Jonathan thought. The floor shifted, and Jonathan realized, with horror, that the house was moving. The entire structure—with them in it—had broken free of its pilings and was floating.

The families huddled in the living room on the second floor. Ralph and Sue Carey, the elder homeowners, sat together on the couch. Their daughter, Michelle, wrapped her arms around her six-year-old son, Will, who was sitting in a club chair. Laura hugged her two children, Andrew and Leighton. Their yellow Labrador, Maggie, sat beside them.

Nothing to do now, Jonathan thought, but ride it out. He and Randy raced to a window, beaming flashlights into the darkness. Jonathan hoped the water would push the house off to the side, onto the banks. But the house kept moving forward. Up ahead, he saw the concrete bridge over Ranch Road 12.

Laura again called 911. It was 11:29 p.m., eighteen minutes after her first call. At first the dispatcher could hear only muffled voices and rushing water. Then a woman’s voice came on the line, breathless and panicked.

“Hello! Our house is down!”

“Hello?” the dispatcher said.

“Hello! Our house is down! We’re floating!” Laura screamed.

“What’s your address? Where are you located?”

“We’re 100 Deer Crossing. Our house is—it’s off the thing! We’re floating! We’ve got three small kids in the house.”

“Okay, we do have a call for Deer Crossing. We’re going to get out there as soon as we can. Are you on the roof of your house, or where are you located?”

No response.

“Hello?”

“Please,” Laura said.

“Are y’all inside your residence still?”

Static filled the line.

“Hello?” the dispatcher said.

The dispatcher heard a woman’s cry, then silence.

Shortly after, at 11:33 p.m., Laura called her sister once more. Laura told Julie that a tree had struck the house and they were floating down the river.

“What?” Julie said, struggling to comprehend.

“Listen,” Laura told her. She did not sound panicked, but calm, determined, Julie thought. “Tell mom and dad, ‘I love you.’ And pray.”

“Where are you?” Julie asked, hoping she could summon help. “How fast is the house moving? What do you see?”

Laura interrupted her. “I have to go,” she said. “I see a light. Do you guys see a light? I’ve got to go. I’ve got to go.”

“Wait!” Julie shouted. But Laura hung up.

About the same time, a man dialed 911. He was downstream from the vacation house.

“Yes, my name is Brian, and I’m in Wimberley. I’m on Loma Vista. A house just went by with the river, and there’s a person in it with a spotlight.”

“Okay, you said, so there’s a house on the river?”

“A house, yes. Just went by, through the river,” the man said gravely. “And there was someone in it with a bright light, trying to flash us.”

He was worried about the house hitting the concrete bridge just downstream. “I mean, that bridge,” he said.

A rescue boat crew spotted the house and tried to follow it. But the water was moving too fast. The firefighters could only watch as the house hurtled toward the bridge.

The Collision

Inside the house, Jonathan and Randy saw the bridge approaching. They thought the house might be able to skirt under it—but it was going to be close. They yelled to their wives to hold on.

At the moment of impact, the house barely slowed down. The bridge peeled off the third story in a violent crash. Windows shattered, wood snapped, walls collapsed. With the ceilings gone, they could see the black sky. Brown waves rolled over them as they bobbed wildly downstream at about 30 miles an hour. When lightning flashed, they saw objects rushing beside them—trees, lawn chairs, picnic tables—crashing into them, tearing apart the house piece by piece. Furniture slipped off into the water.

Sue Carey was the first person to fall away. As she tumbled off the back of the living room floor, she grabbed onto a pile of accumulating debris, yelling for help. Jonathan crawled across the pile and reached for her hand through the frame of a broken window. But as the debris pile between them grew, he couldn’t hold on anymore.

Jonathan crawled back to the group, grabbing his children. Another wave crashed into the house. As Jonathan struggled to regain his hold, he realized their friends—Randy, Michelle, and Will—had disappeared.

Jonathan retrieved a twin mattress. It lay slanted atop a pile of debris, still on the living room floor. He positioned his family together on it: he and his wife kneeled, the children between them, all holding hands. Laura wept, and Jonathan told her again and again, “We’re okay. We’re going to be okay.” As water pounded the mattress, the family struggled to hold on. Jonathan grabbed his son, Andrew. The kindergartener’s hair was wet, his pajamas soaked, as he clutched his father’s arm.

Ralph Carey climbed on top of the mattress with Jonathan’s family. Then a huge wave hit. Ralph fell into the water. Jonathan realized that his son, Andrew, also was gone.

From the back of the debris pile, Jonathan heard Andrew calling for him. Jonathan jumped back, reaching toward his son’s voice in the dark.

“They’re Screaming, ‘Help!’”

Over the next twenty minutes, 911 dispatchers received at least nine calls from residents along the Blanco, calling to report people in the river. Callers couldn’t tell if the people were floating on a house, a car or a boat.

“I’m pretty sure it looked like a boat,” one man told dispatchers. “They were definitely on top of it. They had a flashlight and they were shining it toward the side of the river, obviously, and they were yelling for help.”

Said another caller: “They seem to be floating, but they are in the water moving rapidly. They have ahold of something. They came by really, really fast. They’re screaming, ‘Help!’”

“How many people?” the dispatcher asked.

“It looked like four to five.”

“Four to five people in the river?”

“Yes.”

“Okay. All right, I’m going to get them out there as soon as I can, okay?” the dispatcher said.

The last sighting appears to have come at 11:50 p.m., about a mile downstream.

The Calls Continue

Throughout Wimberley, people kept dialing 911. In call after call, at times a couple a minute, people—including the wife of a city councilman, who was trapped in the attic with her husband and four-year-old grandson—pleaded for help that wasn’t coming. Dispatchers sent details to the firehouse and kept answering the phones.

“We’re going to drown in here,” one caller said. “And if we go on the roof, we’re going to get swept away. I don’t know if you understand the situation. We need help, now.”

“The water keeps rising,” said another. “We’ve only got a few minutes left. Please, try and get here, quick!”

In each call, one of the dispatcher’s first questions was: What’s your address? Over and over, people did not know where they were. Many were tourists. One house had 25 people celebrating a ninety-year-old’s birthday. They did not know cross streets or landmarks.

The dispatchers offered advice that they seemed to sense was inadequate.

Don’t go into the attic. Climb on the roof if you have to. Turn around, don’t drown. They’ll get to you as soon as they can. Give us a call back if anything changes.

“If anything changes,” one caller replied, “I’ll be dead.”

Chief Czichos sat at his desk, listening to two handheld radios. He wrote addresses on a pad as firefighters worked rescues. Emergency tones kept dropping over the loudspeaker, signaling new incoming 911 calls.

Czichos worried about his wife, Diddle, who was home alone. He checked in with his brother-in-law, who was trying to keep his hundreds of guests calm at the family resort. They’d evacuated the cabins, piling families into a hall on the highest part of the property. Water had never before entered their riverfront cabins, built by Czichos’s father in the forties. But tonight the water was carrying the cabins away one by one.

About eleven p.m., a fire lieutenant from Austin stepped into the chief’s office, his blue cargo pants soaked. It was Lieutenant Travis Maher, a water rescue manager with Texas Task Force 1. He was bringing a crew of 36 men and twelve rescue boats. He knew the town well; he lived there with his wife and two sons, and volunteered at the firehouse.

When the chief saw Maher, he looked relieved. It was an incredible stroke of luck that two of the station’s best volunteers—first Burttschell, now Maher—had arrived to help.

By now, the chief was six hours into the crisis. He looks overwhelmed, Maher thought. Sitting in his office, he had begun to focus on individual calls—find one problem, solve that problem—because it seemed the only way forward. With reinforcements on the way, they needed to regroup.

“Chief, you’ve got to get out of this office,” Maher said. “Come out in the operations room, where we can all work together.”

“All right,” Czichos replied, rising.

Maher offered to run the rescue boat crews. Czichos agreed, knowing it would allow him to manage street and bridge crews and deal with city council members, residents, and reporters.

Maher walked to the front of the operations room, studying the white board. He wanted to triage the calls. Who needed help most quickly? Which callers were elderly? Who had kids in the house? It was tough. Nearly every call seemed dire.

The boat teams had arrived from all directions, and more were on the way. But some were locked in the valley by water and couldn’t get out; others were locked out and couldn’t get in.

Around midnight, firefighters began returning to the station house, wet and muddy. Maher tried to give them new addresses, but they shook their heads. They couldn’t launch the boats.

“What do you mean?” Maher asked.

It was too dangerous. The water was too fast, too high, they said. In his two decades as a firefighter, Maher had never had this happen.

These are the best men and the best boats in the state, Maher thought. They lived for tough rescues. It was unfathomable to him that they would be standing there saying, “We can’t go out.”

Residents were now coming to the station, asking for help. Because it was a small firehouse in a small town, people were able to walk right into the command center. They pleaded with Maher to rescue their mothers, fathers, children, friends.

Maher pointed to the white board. They couldn’t reach the houses until the river receded. Near midnight, Maher found himself half-arguing with groups of people, all of them desperate.

One family spotted a rescue boat in the parking lot and asked Maher if they could borrow it. Maher shook his head no. It wasn’t safe. “Where are the helicopters?” families asked. Maher explained that the state did not allow rescue aircraft to fly at night. It was too dangerous.

Residents tweeted and posted pleas on Facebook for help.

“Please come get us at 2000 River Road,” one woman told dispatchers at 2:24 a.m. “This is my fourth call. Please come get us.”

“Okay, what’s changed?” the dispatcher asked.

“Huh?” the woman said.

“What has changed?” the dispatcher asked.

“What’s changed?” the woman shouted. “We’ve been in the water for three fucking hours, that’s what’s changed! I’m freezing. We need somebody here. I’m hanging onto a fucking tree!”

“I understand that,” the dispatcher said calmly. “And this is a recorded line, okay? We’re getting them out there as soon as we can.”

The line went dead.

About this time at the firehouse, Maher stepped outside into the truck bay to get some air. He now had about 120 calls pending on the white board. He dialed his supervisors at the state command center, in Austin.

“All the aircraft that you have access to—I need them here at first light,” Maher said.

“What do you want them to do?” a supervisor asked.

“I want them to engage,” Maher said. “I want them checking rooftops. Checking cars. Rescuing people.”

Maher had no idea how many people they would find. He wondered how many people had died during the storm. Easily dozens, he thought. Maybe hundreds.

The Forecasters

At the National Weather Service office, forecaster Lenz had been monitoring the readings from the one gauge on the Blanco River, in the center of Wimberley. The river registered around five feet at nine p.m. But as the measurements arrived by satellite every 15 minutes, Lenz watched in shock as the river crested to heights he had never seen. In just one hour—from 10:45 p.m. to 11:45 p.m.—it rose nearly 20 feet.

Forecasters had predicted 1 to 4 inches of rain, up to 6 inches in isolated spots. Instead up to thirteen inches fell. They had predicted the river would rise to a moderate flood stage—roughly seventeen feet. But by midnight, the river registered at 32 feet—and was still rising.

It was hard to figure out what had caused the extreme rise. It appeared that the rain bombs had fallen in the exact right spots. Also, the water and debris had backed up at the Fischer Store Road bridge. When the bridge collapsed, it was as if a dam had burst, sending the hulking wall of water into Wimberley.

Telephones rang nonstop inside the forecast center as emergency managers across the region called to check in. How much more rain would fall? When would the river stop rising? Forecasters learned of high-water rescues, of houses floating off foundations, of bridges crumbling. They tweeted out emergency warnings, but it was too late.

“Blanco River at Wimberley is now at 39 feet,” the forecaster center tweeted at 12:56 a.m. “This is unprecedented flooding for this site.”

An air of solemnity filled the crowded operations center. They turned their attention to towns downstream from Wimberley, trying to help their emergency managers prepare for what was coming.

At one a.m., another reading from the river gauge popped up on Lenz’s computer, showing the water at 40.21 feet in Wimberley—a record. Then the gauge fell silent. Lenz refreshed the computer screen, waiting for an update. But none came. The river had crashed into the solitary gauge, pushing it off its foundation.

Shortly after, floodwaters rushed into the next town, San Marcos. Water pushed over the banks onto the property of the Hays County sheriff’s office, where 911 dispatchers were answering calls. The dispatchers evacuated, transferring calls to a nearby station.

Man in the Dark

About six miles downstream from Wimberley, dogs barked in the night. The sound awakened people staying at a vacation house, near San Marcos. The power had been flickering off and on, but the house was high on a bluff, and the occupants had no idea about the flooding.

About 1:30 a.m., Allison Boltauzer, the owner of the house who was staying there for the weekend, stepped outside in her pajamas and pointed the flashlight on her iPhone into the darkness. In the driveway, she saw the outline of a man leaning over a camp chair. He was shaking, his arms and legs covered with gashes. He was wearing American flag swim trunks and one shoe.

“I just got off the river,” the man said. “I just lost my entire family.”

Boltauzer stared at him, confused. Her house was ten miles off the main road, in a gated subdivision.

“Where did you come from?” she asked.

“The river,” the man said again.

“That’s impossible,” Boltauzer said.

Boltauzer called 911, and her guests rushed to find blankets and dry clothes.

“What’s your name?” Boltauzer asked.

“Jonathan,” the man said.

He told her what happened—the vacation house got swept away, and he became separated from his family on the river. He explained that he had grabbed a tree branch and climbed onto the riverbank, trying several times to scale the cliffs but tumbling back to the ground. On his third try he got to the top, limped along the switchbacks to her house, waking her dogs. He told her about every person in the house, saying their names aloud in the dark—Laura and Andrew and Leighton, Ralph and Sue, Michelle and Randy and Will.

“They’re out there,” he told her. “There’s eight of them. I need to find them.”

It took paramedics about an hour to reach the house. At about 2:30 a.m., Boltauzer’s husband helped load Jonathan on a stretcher and noticed dozens of cacti needles sticking out of his arms. His legs were swollen with fire ant bites. He became restless, straining to rise from the stretcher. “I’ve got to go search for them,” he told paramedics. He began to wheeze; Boltauzer could tell he was having trouble breathing.

Jonathan borrowed a phone and called his younger brother, Darren.

“Laura, Andrew, Leighton—you need to go find them,” he said. “They’re on the river.”

He lay back on the stretcher and sobbed.

First Light

The blades of Black Hawk helicopters thumped across the sky as pilots lowered the aircraft into the Wimberley Valley after sunrise. They followed the brown waters of the swollen Blanco, surveying the wreckage.

The river had cleared a passage a quarter mile wide. It uprooted thousands of cypress trees—some of them hundreds of years old—and pitched them into piles, the giant root balls blocking roads and yards. The trees that remained leaned east in the direction of the river’s flow, and the whole landscape seemed tilted. The floodwaters had smashed into two concrete bridges, limiting access to town. The raging river damaged or destroyed about 350 homes, tossing dozens aside as it reclaimed its floodplain. Empty concrete foundation slabs glistened in the morning light, as if polished by the water.

Helicopter pilots hovered over rooftops, spotting people in sleeping bags. Hummers plowed through mud-caked roads to transport residents to shelters.

Later, residents went back to their houses to survey the damage.

Cathy Cunningham, the woman who had grabbed a bottle of gin as she fled her house, dug through piles of mud and debris, searching for the box that contained her son’s ashes. She searched frantically for several days, asking, “Where is this? Where is that?” Her granddaughters, in their thirties, looked at her as if she were possessed. “Granna, at least put on some shoes.”

People wandered into town, with bare feet and blank faces. Christy Degenhart opened her Ace Hardware at six a.m. She sent her husband, Tad, to South Austin to buy one thousand hot dogs. They rolled a line of grills outside, ripped off the tags, and started cooking.

At the firehouse, Chief Czichos focused on the white board. Crews had completed about 150 rescues, yet still had not accounted for thirty to forty people.

Judge Andrew Cable, the county’s justice of the peace, called nearby funeral homes, asking for help. He asked emergency management staff to approach the local grocery store and ask to borrow a freezer truck, if necessary. The store agreed but made it clear that if they put one body in a truck, it was the county’s to keep.

That afternoon rescue workers found the first body, that of 74-year-old Larry Thomas. He and his wife had grabbed hold of a gutter until the river carried Thomas away. His wife clung to a bush for six hours, singing church hymns until a neighbor picked her up in a canoe.

Rescue workers also found the body of 29-year-old Jose Alvaro Arteaga-Pichardo, who had been working on a ranch west of Wimberley, to send money to his family in Mexico. Floodwaters swept away his red Chevy Blazer as he drove home.

Czichos got word that Jonathan McComb had been found, but the other eight people from the vacation house were still missing.

Jonathan lay in the trauma unit of Brooke Army Medical Center, in San Antonio. He had two broken ribs, a broken sternum, and a punctured lung. He called his wife’s parents. “I’m so sorry,” he said, sobbing. “I’m so sorry.”

Jonathan didn’t know how his family could have survived. But what if they were out there, hurt in the dark?

He lay in a hospital bed, staring at the same white ceiling tile. Dozens of friends and relatives arrived at the hospital. He begged them all to search.

Lost, Then Found

Cristen Daniel sat in a chair at a Wimberley church, talking into a television camera for NBC News. Wearing a ball cap and tennis shoes, Cristen talked about the search for her parents, her sister, and rest of the families. Her parents, Ralph and Sue Carey, owned the vacation house. Her sister and brother-in-law, Michelle and Randy Charba, were also missing.

Cristen, 40, told the reporter about their river house, how she had been going there since she was a girl, how she would have been there that weekend if not for her children’s dance recitals.

Her mother had texted her at 11:16 p.m. the night of the flood. No words, just a dark image of water circling the porch stairs of the vacation house, as her father looked on in his boxer shorts. But by then Cristen was asleep 45 minutes away at her home in Austin. She learned of the flood the next day.

Cristen remembered water flooding the property seven or eight times, but it had entered the house only once before, with about six to twelve inches inside, she recalled. She remembered how her father had always told her and her sister, Don’t try to leave, your car might get swept away. He would point to the concrete pillars that supported the house, explaining that steel poles anchored it deep into the rock.

After the flood, Cristen had walked down the driveway and found those pillars toppled, the house gone. She had fallen to her knees.

“How are you getting through this?” the reporter asked.

“By the grace of God,” she said quietly.

As the extended families arrived in town, the scene seemed surreal: they saw tourists eating at an outdoor cafe, firefighters sweeping debris off the bridge. Their relatives were missing—why wasn’t everybody racing around, searching?

The families felt shut out of the search operation. They left the firehouse and began wandering along the river, looking through debris piles, calling their relatives’ names.

They set up a command post in the choir room at the First Baptist Church. They brought in computers and copiers. One family friend, a Boy Scout troop leader, printed out topographical maps and hung them on the wall. They assembled a fleet of a dozen helicopters, from friends and independent contractors, to look from above.

On the first day, Cristen’s husband, Alan, searched the riverbed from a helicopter and spotted a dog in a tree, fifteen feet in the air, hoarse from barking. A property owner rescued it, and etched on its collar was a name: Maggie. It was Jonathan’s dog. The discovery filled families with hope: if Maggie survived, maybe the others had, too.

As volunteers arrived, they fanned out across several counties. Doused in bug spray, the teams combed the riverbed in rows and dug into the piles of debris by hand. The conditions were treacherous: quicksand-like mud, snakes everywhere, picnic tables dangling in trees above. Storms kept forming, spitting out rain and lightning.

Officials, while awed by the family’s resources, were displeased with their parallel search operation. The state had deployed about a hundred workers, specially trained in search and rescue. They cautioned the families against creating “an incident within an incident, a tragedy within a tragedy.” They were particularly worried about the large number of helicopters crisscrossing the skies.

The families grounded the helicopters, but pressed on. Using mapping software, they marked more than 7,500 points of interest—piles of debris, crevices in boulders. They searched roughly 42 miles of riverbed, both sides, a couple of times. Teams hung red or orange ribbons around piles once searched, lime green ribbons for ones they thought should be revisited by dogs.

One group found what appeared to be a child’s footprint in the sand. Was it Andrew or Leighton or Will, lost along the river? Teams combed the area, but didn’t find anything. Another group discovered what they thought looked like a baby. Again searchers converged on the site; it was a fawn.

In all, more than 2,500 people showed up to help. Barbecue truck operators handed out free meals in the church parking lot. One lady made 150 turkey-and-cheese sandwiches. Cristen was overwhelmed. All these people, trying to help.

But as she lay in bed at night, listening to the thunder and rain, she pictured them out there, her sister, her mom. She shook her husband awake. “I want them to be alive,” she said. “But also I don’t. I don’t want them living through this nightmare.”

“Please, God,” she prayed. “Please let us be the miracle.”

Four days into the search, a sheriff’s detective arrived at the church, looking grim. He made eye contact with Cristen and walked toward her. Her heart raced and she knew: We’re not the miracle.

Detectives discovered Cristen’s sister, Michelle, first, curled in a part of the vacation house about 35 miles downstream, in another county.

Then detectives arrived to talk to Jonathan. They had found the body of a small boy on Wednesday. They believed it was Andrew.

As the detective talked, Jonathan walked out of the room and stepped outside alone. He sat down on a curb and put his head between his legs. I want to die, he thought. This hurts so bad. I just want to die.

The next day they found Ralph. Then Sue and Laura. Every time detectives appeared at the church, the volunteers fell quiet.

Later that week, Jonathan asked to see where they had found his son. Cathy Montgomery, the operations supervisor for Wimberley EMS, agreed to take him. She drove Jonathan and his brother to a park along the river, then explained that they would have to hike the rest of the way. As they started along an overgrown path, she noticed Jonathan was limping and having trouble breathing. “Are you sure you want to do this?” Montgomery asked. Jonathan nodded.

As they neared a barbed-wire fence, Montgomery stopped. “This is the general area,” she said.

Jonathan looked at Montgomery. “Do you remember the exact spot where you found him?”

Montgomery hesitated, then nodded. She walked over to the fence and pointed to a small pile of debris.

Jonathan followed her. He stared at the pile, then sunk to the ground.

The Aftermath

In all, twelve people had died in the Wimberley area during the flood, eight from the vacation house. As bad as the death toll was, fire chief Czichos considered the town lucky to have not lost more.

Despite the massive search, two children still have not been found: Jonathan’s daughter, Leighton, and the Charbas’ son, Will.

The feeling around town was that further searching was futile. When the river took someone, it often left them battered, buried beneath layers of silt and mud. One of the people inside the vacation house had been discovered fifteen to twenty feet deep in the ground. It would take another flood to unearth the children, people thought. When the river gives them up, the river gives them up.

Will’s aunt, Kim Charba, refused to stop searching. She had been close with her nephew, having Ninja Turtle sword fights and watching the movie Cars—Will knew every word by heart.

Property owners became used to seeing her, the thin woman in a ball cap, trailing quietly behind a couple volunteers with their search dogs. To her, it wasn’t about finding Will; it was about not leaving him behind.

Four weeks after the flood, more than one thousand people packed the First Baptist Church in Corpus Christi for a memorial. After the pastor spoke and the organ played, Jonathan rose from the first wooden pew. Wearing a black suit, he climbed the steps to the altar, the same spot where he and Laura had wed ten years earlier.

Jonathan spoke to the crowd, reassuring them that his family was in a better place, “up in heaven, looking down at us right now.”

Andrew’s body had come to rest in a fitting spot, Jonathan said. “He was discovered at the neighborhood park, where families go to spend time together, enjoy each other’s company, and where kids can swim and play all day long. That’s exactly what Andrew loved to do, and where he loved to be.”

After the service ended, after the friends and relatives drove away, it was Jonathan and his dog, Maggie, at the family’s four-bedroom house in Corpus Christi. It was filled with Andrew’s Hot Wheels and Leighton’s princess dresses, their crayons scattered across the craft table where they had left them.

Jonathan stayed awake at night, replaying the moments of the flood, dreaming of ways he could have saved them.

In December 2015, seven months after the flood, a couple dozen people sat in a room at the state capitol, in Austin. With approval from the Legislature, Governor Greg Abbott had transferred $6.8 million from a state disaster contingency fund for more stream gauges and better floodplain management across the state. Now it was time to figure out how to spend it.

Steve Thurber, Wimberley’s then-mayor, asked the Texas Water Development Board for more gauges for his town. Without them, every storm is full of uncertainty, he said.

“It’s time for that guessing game to end.”

In interviews for this story, scientists and forecasters agreed with him. The state must do more.

“Relying on an ‘old-timer network,’ in this day and age, in the United States of America, is just not good enough,” David Maidment, a surface water hydrology expert who has taught for 35 years at the University of Texas at Austin, told me.

The state needs better weather data collection—more rain and river gauges, particularly in smaller towns, forecasters say.

“We truly did not know the height of the water until it hit that river gauge in the city of Wimberley,” Paul Yura, a warning coordination meteorologist at the National Weather Service in Austin/San Antonio, told me.

So far, three new gauges have been installed upstream on the Blanco, with more on the way. Chief Czichos already has begun to monitor the numbers as part of his weather checks.

In Wimberley, residents want a better alert system.

“No warning. I said that for days after. No evacuation. No one came at six p.m. saying, ‘You should get out of here,’” resident Vicki Adare told me in an interview.

“I don’t mean to sound judgmental, but I didn’t realize that I lived somewhere that there was no system in place to prevent me from waking up to five feet of water in my house in a matter of minutes.”

The city encourages residents and visitors to register their cell phones for its emergency notification system. Yet some residents say the warnings are so frequent and vague that they become easy to ignore. City officials counter these criticisms by saying many people credited the calls with saving their lives.

The night of the flood, the city’s emergency notification system had placed two more calls to the phone registered at the Careys’ orange vacation house, after the first went to the answering machine. The second came just after eight p.m. The final call came about 10:40 p.m.

“The Blanco River is on the rise now in Wimberley as a result of heavy rains upstream,” the recording said. “River Road is closed. Residents . . . need to monitor water conditions and move to high grounds this evening if necessary.”

Records show that someone picked up the phone at the vacation house. Jonathan said he was not aware of any warning calls. Short of a message that said, “Get out now,” the Careys would have been inclined to stay put, said their daughter, Cristen.

The city also has tested a siren system, as well as mandated that all rental properties have a home phone line registered for its alerts, with posted instructions that renters answer any calls.

After the Memorial Day flood, the Federal Emergency Management Agency drew advisory floodplain boundaries and encouraged residents to build their houses higher along the banks. Wimberley’s city administrator, Don Ferguson, recommended the city council officially adopt FEMA’s advisory boundaries and require homes be rebuilt according to those standards. But the council caved in to pressure from residents who said the requirements would have been too expensive. As a compromise, the council mandated that residents sign affidavits saying they had been told about the recommendations.

“We’re hoping that will at least make people pause,” Ferguson told me in April, “because there’s no question in my mind that the higher elevations are the safer elevations.”

After a months-long appeal process, FEMA will issue its official and final maps. Council members again will have to decide whether to adopt them. If they don’t, city residents will not be eligible for national flood insurance. But by then, many homeowners will have already rebuilt in the old floodplains.

“We’re not learning from what’s happening,” Raymond Slade Jr., a hydrologist who has studied Texas floods for more than forty years, told me.

Human memories are short, scientists say, and people often don’t comprehend the power of water.

Cristen Daniel, whose parents owned the orange vacation house, is deciding what to do with the land. One morning this past winter, she drove to Wimberley after dropping her two children off at school in Austin and wandered across the property.

For her, the site has become both solace and wound. It’s where she feels closest to her family, the backdrop of her happiest memories. A place of warm sun and bare feet and fresh air and laughter. Should she sell the land or rebuild? Can she leave this place behind? Can she trust the river with the only family she has left?

Lately Cristen has been heavy with thoughts of her father, wondering what he must have felt when the house lifted off its pilings, hurtling toward the bridge. He built the house, brought his family there. It pains her to think of what his final thoughts might have been: What have I done?

On a recent April morning, fire chief Czichos stepped out of his house and drove down River Road in his red pickup truck. Fog rose in white wisps along the water. Across the valley, rain drizzled from gray clouds.

Czichos had received emails from forecasters and emergency managers preparing for storms across the state. With more rain on the way, Czichos would spend the weekend checking his new river gauges.

The tourist season was beginning. Every hotel was packed, and long lines of cars crawled through the town’s main road. Hundreds had arrived for the annual pie social and butterfly festival.

As Czichos drove along River Road, he could see dozens of cypress trees still lying along the banks, in various stages of decay.

With the trees washed away, the landscape looked harder, more exposed than ever. Czichos could see the houses once hidden along the cliffs.

The river had made its power clear. But over time, he knew, the trees would grow again and people would forget.

He headed back to the firehouse to prepare for the coming storm.

Jamie Thompson is a freelance writer in Dallas. She can be reached at [email-hidden].

- More About:

- Flooding