I’m only fourth generation. Not old enough to remember buffalo, but old enough to remember my grandmother, who heard her father tell about them, back when Texas was unbounded. Back when the myth I was raised on, half a century ago in suburban Houston, still rang true: that we inhabited the edge of a frontier, a frontier that was owned by us and us alone, and that in addition to being all and always ours, it was spacious, and would never run out. We were special, for having been entrusted with that spaciousness, that sprawl, that emptiness. We had been entrusted with a gift, but also, we were deserving of it.

There had been some bumps, to say the least, along the way—the people from whom we took the land had not wanted to give it up; it must be assumed they loved it too, but we’d ended up with it. The land was so strong and big back then that it must have seemed as if it would live and last forever: that it would always take care of us rather than us having to one day, or ever, take care of it. Back then, it was all about bounty, not diminishment—excess, actually, which became the Texas way, and the greatest excess, perhaps, was that of space.

Except that Texas has always been bounded. For as long as there have been rivers, there have been boundaries. Sometimes the people who have lived here paid attention to them, other times not; the rivers were just rivers and not fences. From the beginning, or what passes for the most recent beginning, circa 1836, we reached for, and desired, more. We declared the Texas territory to reach all the way up into Wyoming, toward Yellowstone—all those snowy mountains, all those not-yet-discovered gold mines, and all those buffalo.

Myths last a long time, almost forever. That’s why they’re myths. Even today, many in Texas imagine we have no boundaries. A place where you can set out walking and never stop. A place where the skies stretch beyond the eyes and therefore, it might seem, beyond the mind. A place so big that time seems to collapse, crumple, vanish.

Time can move plenty quickly—relentlessly, some say—but it certainly never vanishes. Like the rivers that define Texas, time too is a river, cutting always at everything. In our most blissful moments, we do not see this, or we are unaware of it. From the air, however, you see it in an instant: time on the move, and on the prowl. Flying the great blue dome of the state’s vast skies—in a Cessna 182 Skylane, with cameras mounted to the wings and a camera in your lap—you see time intersect, and collide, with the physical. You see its meandering, digressive, sometimes ambivalent passage in the oxbows of the Sabine, and in the erosion at Palo Duro Canyon. You see its rough conflicts with soil in the Red River, and with sand and stone in the Rio Grande.

But first you must reach the sky, to see this drama, this eternal geological conflict, best. The land beneath our feet, and the land below, tells us who we are. It tells us who we were, and who we will become.

It is July 2015, and I am in Marfa with Jay B. Sauceda, a fifth-generation Texan, photographer, and pilot. He has embarked on a singular project—to document the entirety of Texas’s perimeter from the sky—and a few days into it, I join him, hopping into his little plane to see the state’s westernmost edges. The plane, barely heavier than a canoe, it seems, creaks on the runway, as if the mere idea of flying is enough to make it happen, that and one little motor. I used to have a pilot’s license, and the extraordinary feeling of this moment comes rushing back to me—when the curved tips of the wings, and the plane’s momentum, create enough lift for the dream to become real and the ground to fall away and the sky, with its currents and gusts, to lift and grab you. As if you belong to something new now, a new way of being.

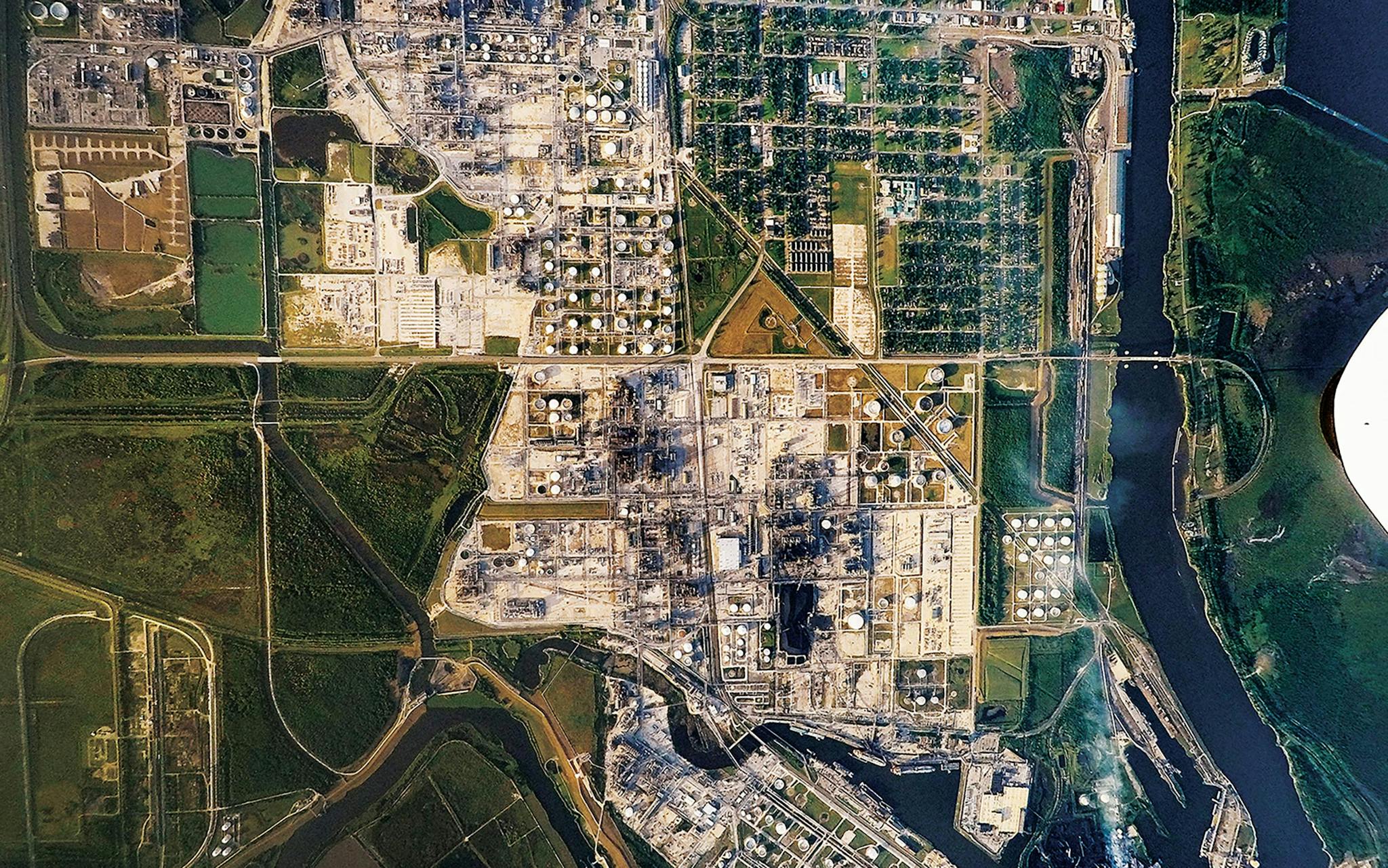

Sauceda loves the state even more than I do. He, like me, has dear ones sleeping at home whom he is keen to get back to—his within the state’s borders; mine beyond—but how he loves to fly, knocking out a few miles, or more than a few, each day, on this grand sojourn. He has recently completed the stretch over North Texas, within a shout of Oklahoma, capturing image after image that I will eventually pore over, filled with wonder, at my desk: oil, oil, oil, patchwork, grid work, pump jacks, frack tanks—a kind of demolition mining, really, more than the old-fashioned hunter-gatherer drilling I grew up with. Then there’s the Panhandle: crop dusters in Dalhart, lined up like military squadrons, man versus soil, man versus nature. Farther on: how quickly, how crazily, the land switches from agriculture to oil—the old swamps, old point bars, mapped by our probings as a baked cake coming out of the oven is tested with toothpicks.

By the end of his project, a six- or seven-day endeavor, Sauceda will have captured more than 44,000 frames of our 3,822-mile perimeter; when I get the opportunity to view a fraction of the whole, a few months after our flight, I’ll end up believing he is creating a new kind of literature for the state, a visual literature that is as significant and powerful as John Graves’s Goodbye to a River, Robert Caro’s The Path to Power, Edna Ferber’s Giant, or T. R. Fehrenbach’s Lone Star. His compositions accomplish what all great work does—offering a new way of seeing things so familiar that we have stopped seeing them.

It was Fehrenbach who noted that Texas inherited wars over its borders at its very birth. That sense of conflict remains, with much heated rhetoric about who may or may not come across those boundaries. Ascend to five, six thousand feet and peer down, however, and you are struck by another war, one involving all nations, as sea levels rise, crops scorch, groundwater depletes, fracking fluids contaminate, and borders dry out, wither, and crack. Dust sweeps across old invisible dashed lines.

And yet, in Sauceda’s photographs, you also see beauty. You see it in the feathered gills of windblown arroyos, the alveoli of deltas. The skin of the earth is a living thing. You are struck by both the colossal force of change and its undeniable splendor, in a way that is both frightening and invigorating. It is beauty just this side of some sort of apocalypse. Our apocalypse, I guess you’d call it. And if time is a river, maybe beauty is as well, striving to insinuate itself between the sharp edges of diminishment and change.

You see this in the coastline stacked with houses, and in the lonely farmland awaiting water that may not be coming back. Though these shuttered glimpses illustrate the terror of overpopulation and resource consumption—the amoebalike sprawl of us, the beehive unification of our needs for food and shelter—you cannot help but also be taken by the curative nature of water, where it exists, and of space, in the vast stretches where there are no people. To fly the perimeter of Texas, then, is to promote a democratic and encompassing affection for all of the state—the peopled and unpeopled—and to train your eye on the beautiful. You are forced to find it wherever it lies, to prove that beauty, like life itself, has a will to cohere, and a will to endure.

The sky reveals the movement of time more surely than the snow reveals to a hunter the tracks of his quarry. Look, you can see it, rushing past, hurtling past, even as we construct arbitrary borders to control it. Three hundred and sixty-five days a year, ten years per decade, ten decades in a century: what could be more abstract than the boundaries we place on time? We fling numbers at the sky while below us the land gallops past. The very stone on which we stand is washing away, the ocean is around our ankles already, and still we hang our calendars on the refrigerator and pretend that time is plodding, or even, in certain hours, motionless.

How drastically our understanding of the story changes with even a modest gain in altitude, and how our perception of time changes as well. At that slightly greater elevation, we can see time for the living thing it is, and can see, too, how powerful it is. How unstoppable. You can start anywhere in this narrative, clockwise or counterclockwise. Sauceda started in Galveston, which once upon a time was the busiest port west of New Orleans. Just an eyeblink ago, really.

In Montana, where I live now—where, too, water is scarce—the borders often consist of mountain ridges, ice-shaved, sharp as obsidian. An eagle glides freely from one state to the next, its morning shadow still in Idaho even as it crosses into Montana. Here in Texas, however—whether in the lush forested country in the east, or the drier red country north, or the thorny lands to the south—the elusiveness of water defines our borders, real or imagined. Is it for this reason, more than any other, that there has been so much war, and for so long? That water, unlike stone, refuses to be owned?

The Sabine, the Red, the Rio Grande, the Colorado, the Canadian: the state’s heart is made of rock and soil, but we are contained by water, which must be shared with the sky, shared with the ground, shared with everything.

There are a lot of us. There are so many more of us than there were before. What are our dreams now? How have they changed? Beneath our feet, does the soil, does the state, still urge us in certain directions? Does the land still whisper to us, and can we still hear it?

I remember my childhood rainy days on the southeastern edge, in Houston, spend listening to the lightning-static crackle of AM radio weather reports calling out hurricane coordinates—Carla, Cindy, Beulah—and I remember the green skies, skies the color of various bruises, birds flying low and fast, and myself hoping, hoping I would not have to go to school that day. I’d plot the slow and curious drift, the coordinates, with tiny magnets on the tracking chart posted on the wall. Hurricane season. A quaint memory now, as if storms were a thing that came within a set bound of rules and time, containable.

Rain drumming the roof, pouring over the gutters, flooding the downspouts, flooding the streets. Land becoming sea, for a few hours, or for a day. It would pass. It would all pass. The sun would come back out, and the waters would recede, for this was the only story we knew.

What a magnificent, treacherous, breathtaking moment in time we inhabit, poised on the knife-edge of foreknowledge and beauty, brevity and permanence. We know that the only thing constant is change; it is, however, only the more violent amplitudes of change that get our attention. Sauceda has an eye particularly for sunrises and sunsets—in heated skies, these are the safest times for any pilot, much less one of a small plane, to fly—and his photos possess a certain narrative wisdom. Aloft, weather is still king, and prudence is golden. The wise pilot chooses caution, moderation, responsibility. There is much that is still worth living for, there is much that is beautiful.

From Galveston, and before our meeting in Marfa, Sauceda flies up over Caddo Lake, the state’s largest natural body of fresh water, and then continues, riding the edge, the slender plane buffeting on updrafts and downdrafts, as if it is not the air that is in constant pitch and turmoil but the land below. Riding the edge and looking inward, pondering what the borders seek to contain, and what they seek to exclude. History is contained, for certain. Just a few miles back, Kemah, which once boasted a boardwalk to rival Coney Island’s, now holds little houses like the mites between feathers on a great resting wing.

Rotating westward, turning away from water, Sauceda heads toward another destiny. The gravity of water to the east is different from the gravity of soil, land, rock to the west. It’s still Texas—still the same state—but another nationality.

In Marfa, we lie low for a while as the heat coils, pulses, rises, falls; as great herds of cumulus approach from the west, drift toward us, the sky above filled as if with millions of bison, lightning cracking from their hooves, the sky and the land washed clean again. Calm blue sky returns, the scent of all things almost—briefly—intolerably fresh. Something like coolness, even in summer. A moment of it, at least: five, ten minutes, maybe right at dusk.

I left Texas because I could not walk the land. I loved it but did not own it. I traveled west, to the public land of our national forests, owned and shared by all Americans, land where I could step into a forest and begin walking, never encountering a fence: walking my land, our land, the land of all those who came before us and all who will come afterward. Sauceda has traveled too, climbing to a sufficient height where borders, fences, and boundaries dissolve. They may still be visible, but they are not nearly as meaningful—in that grappling between sky and time—as they are on the ground.

I don’t like trespassing, and I don’t like having to always be hitching my leg up over barbed wire, mid-stride. I like to go without stopping. And I have a fantasy, a dream, in which some of the large landowners of this corner of the state band together to tear down their rusting, windblown barbed-wire fences—strainers of wind and sometimes tumbleweeds, nothing else—to allow nonmotorized public access, so that a young person can walk for days, sky-staring. Walk toward a mountain. Walk up and over that mountain. Walk down the backside, and onward, across the land he or she was born into, or came to.

This is how it was in my mind, as a young person born into Texas, and it took me a long time—eighteen years—to realize that it was a myth: that the land did not belong to me and that I would have to go, then, to a place where that dream could be made real. But flying, on the heated currents of the land’s breath—particularly the stony land’s breath, out in West Texas—makes me think it could one day be possible. Someone, or some two or three people, will need to be generous, visionary. Mythically so. But there is still a little space left down there for all of us. I don’t know exactly what that would look like. Maybe not all that different from what it looks like now—but forever, or as close to forever as time can get.

We end up killing another day in Marfa. The world is too hot—the sky is blue, but giant pearl-white clouds are beginning to form, columns of almost otherworldly energy, or energy to come. Sauceda is the most conscientious—smartest—young pilot I’ve seen. I believe the odds are good he will become a good old pilot.

The weather people are telling him we could probably fly, and he’s eager to round the horn, to continue on the last leg of his journey and make it on back home and see his family. “But I don’t want to be a statistic today,” he says. We visit friends of his instead, at a barbecue. I sleep in an empty mansion. The hospitality, generosity, of strangers.

We awaken early, alive, to as beautiful a summer predawn as can be imagined. Stars. The world below not yet made. We fix coffee, saunter out to the airport. The lip of sun just rising, shimmering, as we check the airplane to see how it fared in the night. No surprises. Meticulous. Steady, mourning doves calling.

We climb in, start the engine, with its familiar hiss, wheeze, gasp, then hear its throaty, burbling catch; Sauceda punches the rudder pedal in, pulls the throttle out, swings the tail around in a 180, and taxis us down the empty airstrip, faster and faster, until we ascend, as if into paradise.

Aloft, you can see stories not available to you below. Stories you might blunder past at ground level. You can see how little difference there is between anything—how similar all things are, or once were, before the world began its work on its one-lump blockiness, its initial oneness. Up higher, you see how wind is almost no different from water: how both move in currents and waves. You see sandstone waves of dunes frozen in time, mid-crash, sand wind-rippling like water, then frozen again.

Aloft, you can see the narratives. It’s a little like landing in a foreign country where you’ve never been before and finding, nonetheless, that you understand what is being said and—important, this—how to speak. Clumps of deciduous trees upwind of a refinery, green and glowing, looking like lettuce or kale in a grand garden, healthy; then the refineries right next to them; and then trees downwind, gray and crippled. The membrane between them—a chain-link fence, nothing more—as invisible from the sky, in this new narrative, as it is to all the other participants in the narrative, but we can tell what’s going on. We can see what’s happening.

It shouldn’t surprise us that we can see more from a mile up. What if all residents of a place could have this view? I think we would think more about our past. I think we would think more about our future.

What would change? Much, I want to believe.

Rick Bass is the author of thirty books, including For a Little While, All the Land That Holds Us, and The New Wolves.

- More About:

- Longreads