Late on an August night in 2013, Tania Joya found herself stranded with her husband and three young sons in a Turkish city not far from the border with Syria. The hotels were jammed with refugees, and the family had nowhere to go.

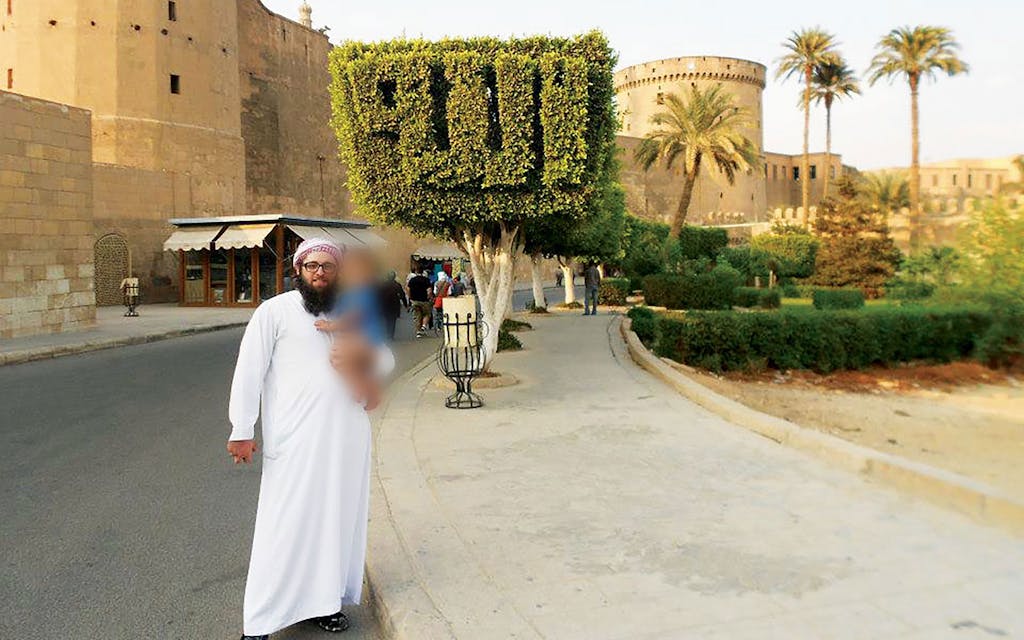

Her husband, a convert to Islam, was a Texan, from Plano. Tania, who had been raised outside of London, had been married to him for ten years. They had most recently been living in Egypt but had been forced to flee that country amid the chaos that followed the 2013 ouster of the Muslim Brotherhood–led government. They’d headed for the eastern Turkish city of Gaziantep, about thirty miles from the Syrian border, where people spoke Arabic and her husband could find work. He was a jihadist—soon to become one of the most senior Westerners in ISIS—who dreamed of helping form a caliphate, an Islamic kingdom to rule the world. She was growing increasingly disenchanted with his quest.

Standing on a dusty street that August night, Tania, who was five months pregnant, was furious. The family had been living like nomads for a decade, and she was sick of it. As Tania argued with her husband, a rundown minibus pulled up, letting people on and off. Her husband talked to the driver, then turned and said, “He knows a place where we can stay.” Tania was hesitant. Would this be safe? But she told herself not to have a public meltdown. They needed a place to sleep. She and the kids were so exhausted they could barely stand. So the family piled onto the bus, squashing into seats with a dozen others. It was an enormous relief just to sit down and close her eyes. She had no idea where they were headed.

As the bus rolled through the predawn darkness, carrying the family south of the city, Tania began to suspect they were headed for Syria. Her husband had been wanting to go there; he’d been talking about it for weeks, but she had vehemently objected. She did not want to take her kids into a war zone. The country had become one of the most dangerous places on earth, with rebel groups, terrorists, and warlords all fighting with the ruthless government. She confronted her husband, who confirmed her suspicions. “It will just be for a few nights,” he said. She was livid, but there was little she could do. They were already approaching the border. She looked out the window and saw graffiti on a wall. Scrawled in broken English, it read, “Welcome in Syria.”

They were already approaching the border. She looked out the window and saw graffiti on a wall, scrawled in broken English. It read, “Welcome in Syria.”

As a girl growing up in a suburban town north of London, Tania Joya liked the usual things—riding her bike, hanging posters of fluffy animals on her walls, and dancing around her room to house and garage music—but she felt unwanted, both at home and in her community. Born in 1983, she had been given the name Joya Choudhury, but her family, friends, and teachers called her Tania, a name her mom preferred. She was the fourth daughter of her Bangladeshi-born parents. “The fourth unwanted daughter,” she said, citing the deeply rooted cultural belief that boys are more worthy than girls. “Families have babies after babies, hoping for a boy.” She recalled how people would meet her father and sympathize, saying, “Four daughters, I’m so sorry.” He would shake his head and sigh, “I know, I know.”

Her family never had much money but managed to make a go of it. Her father worked for an airline, while her mother ran a small catering business. The family home was affordable because of its location, right next to a halfway house. The ex-cons weren’t too thrilled about their nonwhite neighbors. “They smashed our windows,” Tania recalled. Assuming the family was Pakistani, they would yell, “Pakis, go home!” Sometimes, they’d use the roof of the family’s car as a toilet.

“I remember being five years old and wanting to run away,” she said. One of her fondest childhood memories was a visit to Bangladesh, where she stayed with wealthy relatives in a white-pillared mansion with a cricket field and a pond. She loved Bangladesh, despite acquiring a mysterious rash while she was there. She felt at home among people who looked like her. “Nobody treated us like we were second class,” she said. “I thought, ‘Why can’t we live here?’ ”

Her family was Muslim, and her relatives encouraged her and her sisters to dress modestly in loose pants and long skirts. “If I snuck out with bare arms, Bengali men would say, ‘Don’t you have any shame?’ ” she said. Tania never felt close to her father; she described him as verbally abusive. “I didn’t respect him as a role model,” she said. In primary school, she had a mix of middle-class and working-class friends but faced slurs from bullies, who called her “darkie” and “Paki.” She refused to back down, talking right back to them.

When Tania was around seven years old, her father was laid off and started working odd jobs, but he couldn’t hold on to any of them, sending the family into debt. At school, Tania wrestled with dyslexia. And she had to have surgery on a bone that was growing oddly, jutting out of her leg. Her mother began taking in foster children to help pay the bills while also trying to raise her own kids, an overwhelming task that left her exhausted and depressed. When they argued, Tania’s mother would yell at her daughter, “I wish I’d never had you!”

High school didn’t go much better. Tania began to feel sick and noticed a slight protrusion in her abdomen. “I thought I had cancer,” she said. “People said I was a hypochondriac.” Relatives and doctors dismissed her concerns. She looked up her symptoms in a book, diagnosing herself with a tumor. In the meantime, her health concerns inspired her to turn to religion. She had grown up reading the Quran, per her parents’ wishes, but had not taken religion very seriously. Now she started praying regularly. “I thought I better start praying because God must hate me.”

When her family moved from the town of Harrow to a more affordable place in Barking, a suburb east of London, Tania transferred to a high school there and made a new set of friends. They were devout Muslim girls, and they pressured her to become more devout herself. She began reading the Quran closely, taking it to heart. “I thought I had been living a lie, being ignorant of Islam,” she said. As her devotion grew, she said, “I started wagging my finger at my family, judging them, calling them insincere Muslims.” She became best friends with an Algerian girl who wore a jilbab, or Islamic robe, and her friend encouraged her to wear one too. Tania thought it would prove how pious she had become. Her family felt differently. “When I first brought it up to my parents, they hated it,” she said. “My sisters were angry at me. But no one could tell me why.”

When she was seventeen, she saw news of the 9/11 terror attacks on TV. She went to school and told a friend, “Isn’t it terrible?” Her friend replied, “Is it? Is it so terrible?” Some of her new friends were members of ultra-conservative groups and were supporters of jihadism and political Islam. They saw the attack as retaliation for persecution of Muslims throughout time. “I was intrigued,” Tania said. “At school I was studying social sciences, government, politics. When September eleventh happened, I became aware of political Islam.” She started reading about the history of Islam, skipping school to spend time in the library or bookstores.

She read up on jihad. The term, often associated with terrorism, has different shades of meaning, she noted, including a personal struggle to better oneself and a wider struggle to fight disbelievers and tyranny. “Every Muslim is supposed to have their own little jihad; some go in a violent way, and others just do the self-jihad,” she said. She was drawn to war because she had come to believe there was a war against Muslims. She decided that to reject jihad meant rejecting much of the history of Islam, since the Prophet Muhammad “expanded through war,” she said.

As her devotion grew, she said, ‘I started wagging my finger at my family, judging them, calling them insincere Muslims.’

She began to feel that wearing a jilbab would “prove my religious devotion,” and she bought one at an Islamic bookstore. “I was trying to prove that I’m not ashamed of who I am. Growing up in Harrow, I had been ashamed of it. People would say, ‘Oh, you’re a Muslim? You’re not allowed to have fun. You’re not allowed to do anything.’ There was a stigma. But when I moved to Barking, it was a more working-class area. People were more religious, and there was a stigma for being too Westernized. If girls wore jeans or makeup, they would get slut-shamed. I got teased for coming across as too Western. They called me a coconut—brown on the outside, white on the inside.” Part of the appeal of the jilbab was that she could “escape from the negative attention,” she said, including harassment from boys, who would grope her in her Western clothes. “I was getting all these mixed messages.”

And so, one morning she wrapped herself in a jilbab and wore it to school, along with a niquab, or veil, covering her face. She showed only her eyes. When Tania arrived, her new friends applauded, but not the administrators. The principal told her to remove the veil. “He called me in and said, ‘You’re not wearing this. Once you get past the school gates, that mask comes off.’ Then he asked, ‘You’re such a beautiful girl—why would you wear this?’ I said my religion is more important than my looks.”

Her parents were alarmed too. “My dad hated it. I was just being yelled at and being told, ‘Why do you have to do this?’ For them, it was going backward, and they didn’t know why I wanted to go backward. For me, it was, ‘Well, I’m trying to share something that I have pride in,’ because I’d never been proud of anything until then. They didn’t get it.” Employers balked as well. When she applied for jobs at local clothing shops, she was told she would need to shed the robe. Strangers on the street jeered, “Go marry bin Laden,” or “Got a bomb under there?”

It’s a familiar path to extremism for European youth. Feeling disenfranchised and alienated, and unable to find their place in Western society, they turn to extremist ideology. As part of a HuffPost video series, Zainab Salbi, a humanitarian activist, recently met with moderate Muslim families in suburban Paris whose sons had joined ISIS. French Muslims told Salbi they feel stereotyped and ostracized, labeled as “bad” by the media. They said that no matter what they do, they feel they are seen as different—conservative, backward, a thief, a terrorist. Salbi said that it’s easy to blame religion for extremism, but it’s not the root of the problem. “It’s a societal issue, and everyone needs to be part of it.”

One attraction of radicalism is that it “promises you a chance to change history,” said Lawrence Wright, an Austin-based journalist who’s written extensively about terrorist groups, including in his most recent book, The Terror Years: From Al-Qaeda to the Islamic State. “That’s a very powerful beacon for people who feel like their lives are being lived without purpose.” Europe has a particular challenge. “You have large pockets of Muslims, typically in impoverished suburbs, disconnected from the main culture, which causes great problems with education and job opportunity. So they feel alienated and marginalized,” he said. “If you have young people who are second-generation, let’s say Moroccan or Pakistani or Turkish, they don’t feel authentically French or Belgian or British. Oftentimes they’re not treated that way either. And maybe they’ve never been to the country of their parents’ origin. So they’re very adrift. When they ask themselves the question ‘Who am I?’ the answer that they can rely upon is ‘I am a Muslim.’ That takes precedence over the nationality. If you make that declaration about yourself, and you are young and alienated and maybe angry and frustrated, or have few outlets, you go to the mosque and you meet other young people who are just like you. That’s where the process of radicalization often takes place.”

As Tania continued to wear the jilbab and tsk-tsk her family, she became more isolated. At the same time, her stomach was protruding more prominently, and a doctor told her she needed to have an MRI. She simply wanted to escape from it all. And so, in 2003, at nineteen, she went on a Muslim matrimonial site. An American convert to Islam named John zoomed in on her. “He kept pestering me, sending me messages,” she said. “I wanted someone older, someone who had experienced life. He was two weeks younger. He was just a boy to me.” She showed his profile to her relatives and friends. “I didn’t trust my own judgment,” she said. “I didn’t have the confidence to think for myself because I thought that I needed God and religion to think for me.” They thought he was handsome, with his dark hair and eyes. They also liked that he was an upper-middle-class American. He was persistent in his pursuit. “He was courting me, writing poetry to me, telling me everything I wanted to hear,” she said. “He promised travel, a big family, a stable life.”

The Texan was living in Damascus, Syria, at the time, studying Arabic. He had grown up in a politically conservative American family with no background in Islam. Journalist Graeme Wood is one of the few to report extensively on John’s life. According to Wood’s book The Way of the Strangers: Encounters With the Islamic State, the family moved often when John was young, eventually landing in Plano. Like Tania, he’d battled childhood health issues, including tumors and fragile bones. In his teens, he rebelled by doing drugs, including pot and acid; when his father punished him for it, he felt angry at both his dad and the government for criminalizing drugs, particularly marijuana, which helped him with depression. He studied at a junior college in Bryan and took a course on world religion, which left him wanting to know more about Islam. He sought information from local Muslims, and the more he learned, the more he wanted to get involved. Two months after 9/11, he had converted to Islam. “Anti-Muslim sentiment in America was reaching new highs,” Wood writes in his book, “and in central Texas, conversion to Islam would have been a singular act of rebellion.” John had also taken an Arabic name, Yahya al-Bahrumi.

One morning she wrapped herself in a jilbab and wore it to school, along with a niquab, or veil, covering her face. She showed only her eyes.

After about a month of exchanging emails in 2003, Yahya and Tania agreed to meet in London. When she first saw him, at her uncle’s home, he was not exactly what she’d expected. “He was wearing shaggy, tattered clothes. He had a short beard. I thought he looked like a prophet from medieval times,” she recalled. It was a departure from his profile picture, where he looked more polished. The meeting was awkward. “I was so embarrassed I kept giggling,” she said. “I didn’t find him attractive, but I felt pressure to like him. I thought, he’s come all the way from Syria; I felt an obligation.” So she focused on the things she liked about him: his knowledge of Arabic and Islam, and the promise of traveling the world and living in the Middle East, which sounded exciting. Plus they shared a budding curiosity about jihad. She had been protesting the U.S.’s march toward war in Iraq, and when the protests didn’t make a difference, she said, “I felt like I needed to do something more. I began to see jihad as a solution.”

Her parents approved of him, impressed that he’d come from a privileged American family, and they knew that their daughter would do whatever she wanted, regardless. She found herself agreeing to marry him. After all, she said, “He was the most interesting and intelligent person I had ever met. I knew I could love him with time, and I was right.” Three days later, on March 18, they held a secret religious marriage ceremony. But still, fear and uncertainty loomed. “I remember throwing up that day,” she said. “But I thought, ‘How do I go back on this?’ ” At the ceremony, she wore her jilbab. “The imam asked, ‘Are you being forced?’ I thought, I’m forcing myself. I was crying my eyes out. John was patting me on the back, saying, ‘I’ll take care of you.’ It was the first time someone was really nice to me.”

Two months later, they held another ceremony, this one with her family. She recalled her father saying that he now had “one less mouth to feed.” She was not sad to say goodbye either. The newlyweds went to visit her in-laws in Texas. When Tania saw the upscale suburb of Plano for the first time, with its elegant homes and flowering trees, she was wowed. “I thought, this is the life. John said, ‘This is all a deception to deceive your heart away from God.’ ” The couple settled in College Station, where he had converted and still had a circle of friends, and where, living off money from their wedding, they spent their days hanging out, studying and discussing Islam. Yahya became her spiritual guide, and she deeply admired his knowledge. Wealthy Arabs in the community helped fund his studies. She also liked his friends, who were mostly foreign students. “I felt this kindness. It was so alluring,” she said. “They held a wedding party for us at the mosque. I was intrigued by meeting people from all over the world.”

But marital strife came quickly. He expected her to be a subservient wife, a role she had a hard time accepting. “I found him really chauvinistic. He would say, ‘Independent women have attitude problems.’ ” Nevertheless, she said, “I told myself to have patience, to just put up with it. I worshipped him because I thought God had put him in charge of me. I thought I needed to be a good Muslim woman. I was taught in my religion that obedience to those who have authority over you is obedience to God. And men are given authority over women in Islam. So I was at war with myself.” Meanwhile, she was melting in the Texas heat, covering herself with the Islamic robe and veil. “I would say, ‘It’s too hot.’ He would say, ‘Don’t complain. Have fear of God.’ ” Sometimes she looked at herself in the mirror and questioned her choices. “I thought, ‘Why am I hiding myself? Why am I hiding for God?’ I missed the wind in my hair.”

They didn’t stay in Texas for long, leaving to crisscross the globe. First they went to London, where Tania had a seven-and-a-half-pound benign tumor removed from her abdomen. As it turned out, the protrusion and pain that began back in high school had been a tumor all along. When it came out of her tiny frame, she said, “I thought, ‘This is God trying to relieve me of my sins.’ In Islam, there’s a saying of the Prophet Muhammad that when Muslims suffer, their sins are being released like the winds blowing the leaves off a tree.”

After London came Damascus. The Syrian civil war was still years away, but an atmosphere of revolt was beginning to materialize. The couple met other jihadists and dreamed of a caliphate. “John and I were so thirsty for an Islamic state. I was so young and naive, I painted this rosy picture in my mind. I was picturing a utopia.” They were drawn to Syria, she said, because “the prophecies told by Muhammad said that the Messiah, Jesus, was going to return to Damascus with an army of believers, and there would be an apocalyptic showdown.”

Her husband began growing his beard and hair long, wearing tunics and cropped pants. Tania was displeased with the look; she wanted him to look more moderate so he could get a good job. As she recuperated from her surgery, she started to feel lonely and discontent in Damascus. “I wasn’t able to leave home without his permission,” she said. She was also hungry. “John wanted us to live like poor people. He thought living as an ascetic would make him closer to God. The prophet says the poor enter paradise first. It’s kind of like getting programmed. I thought I was getting educated by him. You’re taught that this life is a dream; the next life is the eternal reality.” Neighbors noticed how thin she was and began bringing her food. When she got pregnant, she told her husband she wanted to stop wearing the veil because it was unbearable. He consented, for a time.

They returned to England, where he gave religious lectures online and in person to the pro-caliphate community. The couple legally wed in October of 2004 and moved to Torrance, California, where he had some Syrian friends and hoped to work as a counselor in a mosque, but his extremist views were not in line with those of the mosque. Tania gave birth to their son on her twenty-first birthday. Growing weary of the unsettled lifestyle, she fell into postpartum depression. In addition, her baby had colic, which led to a new frustration: “John was against giving pharmaceutical medicine to the baby. He only wanted alternative medicines. He believed in conspiracy theories that pharmaceutical companies wanted to get everyone addicted.”

Dressed in her robe and veil in California, she heard the usual jabs, with a group of young women saying, “Hey, it’s not Halloween!” She later admitted, “I actually thought that was funny.” The couple moved to Dallas, where he got a job as a data technician at a server company called Rackspace. He visited a jihadist online forum at night and offered tech support to Jihad Unspun, a propaganda site. He also sought ways to use his day job to wage jihad. In April 2006 he was arrested for accessing the passwords of a Rackspace client, the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, a lobbying group that advocates pro-Israel policies. Tania said his plan was to hijack the website and post an essay about why America was wrong to go to war with Iraq. He was sentenced to 34 months in federal prison.

With her husband behind bars, Tania headed to London, where she stayed with family and friends. Tired of living like a nomad, she was considering a divorce. “I told him, ‘I don’t want to live in a home with no furniture. I don’t want to sleep on the floor.’ He begged me to stay.” And so she did. She still believed in him, and in a caliphate. Later she moved to Plano and began to homeschool her son. Her clothing caused anxiety there as well. “The neighbors wouldn’t say hello to me because of the way I was dressed,” she said. One day she came home from the library with her son to find a neighbor and his friends standing outside her door, glaring at her as she approached. She immediately turned around and left.

After that, she told her husband she would not wear the robe and veil but only a head scarf, or hijab. Stuck in prison, he was losing control of her, and he didn’t like it. He ordered her to cover herself in the religious robe when visiting him in prison. “He didn’t want his friends at the jail to see me as a modern Muslim,” she said. On her own in Plano, she got a taste of freedom and began wearing colorful head scarves, form-fitting clothes, three-quarter-length sleeves, “all the stuff I had been wearing under the robes.” She also got a TV and started watching news shows, hearing different viewpoints. She became interested in libertarianism. “When John first went to [prison], I didn’t have the confidence to think I could think without him,” she said. “But now I was seeing different perspectives on life, on human rights, human values. I was still trying to be a good Muslim, still trying to obey him. That’s where the clash began.”

When he was released from prison, the couple moved to Richardson and realized how much they had grown apart. While he had been isolated and immersed in studies of ancient Islamic history in prison, she had been asserting her independence, teaching dance and yoga to Pakistani women. “He was upset,” she said. “I was getting in tune with American culture. He wanted me to dress Islamically. He would say, ‘Oh, look at you. Aren’t you so American?’ ” Her views were shifting too. Publicly, she supported her husband, but privately her devotion to him, and to his cause, was waning. “I wanted to be American,” she said. “I started questioning him, questioning his thinking. The idea of a caliphate was still important to me, but I was a mother now.” Her son became her top priority. She wanted a stable home. Her husband wanted her obedience. “He would tell me, ‘Stop doubting, just obey.’ ” They fought often. “I would argue and say, ‘I don’t want to wear the hijab outside,’ and he would say, ‘Then you can’t go out of the house.’ I was emasculating him. I had to outwardly pretend that I was supporting him, but inside, it was war.”

Yahya had to spend three years on probation. For Tania, this was a blessing, because it meant the family had to stay put. During their time in Richardson, he found work fixing computers and doing IT for an online shoe store. She gave birth to their second son. And her husband took another wife in London, a deeply conservative Salafi woman the couple knew. He married her by phone while Tania fumed. She felt she had to go along with it, as she had nowhere else to go. “I couldn’t go home,” she said. “I had never felt supported by my family.” But she was desperately unhappy. “I wanted to kill myself. I told John I would drive into the lake behind our house. I said, ‘I want to be happy.’ He said, ‘You’re not supposed to be happy in this life. This life is prison. The next life is paradise.’ ”

As soon as his probation was up, he wanted to move again. In October 2011 he took the family to Egypt, where he felt he might escape the attention of the American government. He told his wife he could get a good job there without a felony on his record; he promised a nice home and nannies. She was now pregnant with their third son. It was a historic moment in time: the Arab Spring uprisings had forced out the presidents of Tunisia and Egypt. The region was erupting.

In Egypt, the family moved around, as usual—Al Rehab, Mersa Matruh, Cairo—while Yahya translated fatwas and continued his studies. He gave online seminars in Arabic and English about preparing for a caliphate, according to Wood’s reporting. By early 2013, protests against President Mohamed Morsi, a Muslim Brotherhood candidate elected a year earlier, were growing violent. In July, he was ousted in a coup. Tania and her family were living in Cairo at the time, and she heard the sounds of helicopters and gunfire in the night.

To add to her anxiety, her husband began talking about wanting to move to Syria, where a civil war had begun. “He felt like he had to go and help Syria. It’s a Muslim’s duty to help your family. I felt for the Syrians. They are wonderful people, but I didn’t want to bring my boys to a war zone. They were children. It wasn’t their fight.” As her brawls with her husband escalated, he became physically abusive, and she wanted out. “It came to a point where I told him, ‘I don’t love you anymore.’ I felt suffocated. I would say, ‘One of us is going to need to die.’ He would say, ‘I could break your neck.’ ” One night, she put a pillow over his head in bed. He woke up and forced her off. “I didn’t really think I’d kill him,” she said. “It was more of a cry for help.”

With the fall of the Muslim Brotherhood–led government, the couple no longer felt safe in Egypt. “There were tanks roaming the streets,” she said. “It was a military state.” In August 2013, they fled to Turkey, flying to Istanbul, then traveling to Gaziantep before making their fateful trip to Syria.

At the Syrian border, armed men stopped the minibus at a checkpoint. Her husband talked his way through, claiming the family was Syrian. They walked into Syria and were immediately confronted by members of a militia group, draped in camouflage and guns, interrogating people just across the border. Yahya told them he knew important people—Islamic scholars in Egypt. They let him pass and even offered the family a ride to the nearby city of Azaz, where they were dropped off at an abandoned house whose windows had been blown out. There was no electricity. “I felt like I was in a horror movie that wasn’t ending,” Tania said.

In Syria, Tania found herself in a decimated land of sullen faces, shattered windows, and ever-present debris. It was a different country from the one she’d lived in a decade earlier. Her husband promised, “We’ll just be here a short time—just two weeks.” She desperately wanted to hold him to that promise, to keep her boys safe. “I felt such pure love for them,” she said.

It quickly became clear how much danger she was in. When she stepped outside with her husband, she faced immediate threats. Militants had come from across the world to engage in jihad. She was wearing just a head scarf, not covering herself fully in a robe and veil. Militants would demand that she cover up. They would say, “Are you asking to be raped?” Yahya would say, “I know. She is a problem.” She was in a precarious position, both on the streets and at home, disobeying and embarrassing her husband by publicly arguing. But she had reached the brink. “I was mouthing off,” she said. Jihad wasn’t about “academia, theory, and dreaming” anymore, she said. “Now it was real.” And she wanted no part of it. Yahya, however, was in his element.

Tania stayed home while he networked with the local Islamist militia. “There were shootouts on the streets,” she said. “I would peek out the window, and the fighters would yell, ‘Put your head inside!’ ” Her husband made friends with various militants, who gave him a hand, delivering water for the family and a tank of gas for the stove. Food was hard to come by, and they ate mostly eggs, bread, and shawarma sandwiches—chicken with mayonnaise and pickles. For light, they used candles. She didn’t know it at the time, but her husband was getting involved with the pro-caliphate group that would later come to be known as ISIS.

It was an incredibly dangerous and chaotic time in Syria, says Lawrence Wright. By 2013, the government was violently cracking down on rebels, and the country was fractured. “It wasn’t just one force against the government—there were thousands of different militias. Nor was the Islamist portion of that rebellion unified. Many of them were fighting each other rather than the government. You didn’t know who was your enemy—perhaps everyone. So it was very, very dangerous, and there was no clarity about who was stronger, who was going to win. And in this chaos, people began to be kidnapped, Westerners in particular.”

After a few days, the family went to stay with a woman whose brother was a rebel fighter, thanks to more connections her husband had made. “He was always talking to people,” she said. “He could be very charming.” Her sons, who were eight, five, and one and a half years old, were getting sick. Tania realized the family would not be leaving Syria within two weeks as promised. When her husband got a cell phone that worked in Syria, she called a relative and said she needed to escape. Then she said to call the authorities and report her husband.

One day, after they’d been in Syria about three weeks, he said, “I’m not going back.” Tania was devastated. “I was on my hands and knees, begging him. I was pregnant, just begging him to take us to the airport. He didn’t listen. I told him, ‘F— off.’ He said, ‘No, you f— off.’ I said, ‘Can I? Can I go?’ He said, ‘Yeah, just go.’ ”

She didn’t know it at the time, but her husband was getting involved with the pro-caliphate group that would later come to be known as ISIS.

Two days later at dawn, Yahya packed the family into the back of a van to take them to the border. There were no seats for them, just sheepskins on the floor. Turns out, departing Syria wasn’t as easy as entering. There was fighting along the border, and different militia groups controlled various areas. The family couldn’t get out where they had come in. The van driver took them as close to the border as the militia would allow and then let them out. He said the family would have to continue the journey on foot—about an hour’s walk to a barbed-wire fence with a hole in it, which they would need to pass through to enter Turkey. With suitcases, a stroller, and kids in tow, she and her husband rushed toward the border, surrounded by olive trees and signs warning of land mines. Tania began feeling contractions from stress and dehydration. Syrian refugees who were making the trek with them gave the family water.

As the group of refugees approached the border, snipers began firing from towers, sending everyone fleeing for their lives. The family dashed to the fence,went through the hole, and ran toward a waiting truck. Yahya had arranged for the driver to bring Tania and the kids to a bus station in Turkey. The driver was a human trafficker smuggling refugees. Yahya paid the man, then turned and ran back toward the border, with bullets still flying past. “He never said goodbye to me or the kids,” she said. “I was in utter shock.”

While Tania and the boys climbed into the truck with Syrian refugees, the traffickers began brutally beating a man. “Apparently he had done something to get us shot at,” she said. The truck left him behind.

However, the driver didn’t take Tania and the boys to a bus station as directed, instead dropping everyone off at a random spot by the side of the road. They were near a hill in the countryside, seemingly in the middle of nowhere. “Everyone scattered,” she said. She and the boys stood there alone, crying. Walking up the hill with the kids in the hot, dry air, she called her husband on her cell phone. “I hate you!” she yelled. The connection was bad, but she kept calling and shouting. “See you in hell!”

As they walked, a man on a motorbike approached, but they didn’t speak the same language, and communicating was difficult. He indicated that he would take the boys on the bike, one at a time, to the bus station. Tania was terrified to send her children off with him. He could be trafficking in sexual slavery, or human organs. But she had no other options; she had to trust him. He drove the kids one by one, as promised, and the boys waited for their mom at the station. Then the man drove alongside Tania as she walked with the stroller to the station. As a Muslim woman, “it wouldn’t have been appropriate for me to sit with him on the bike,” she said.

At the bus station, she met up with a contact arranged by her husband. He was in the business of helping Syrians and refugees, and he got them to the airport. They flew to Istanbul and checked into a hotel. She was six months pregnant and only 96 pounds. Lying in bed, feverish, Tania had visions of her husband at the hotel door. “I’d call his name, but the mirage would disappear,” she said. “It made me so sad.” Confused and alone, her emotions raced. “He did give me permission to leave—I never would have known how to get out of there without his help,” she said. “Had I stayed, I probably would’ve been sent to court and tried for apostasy.”

Seeing how sick she looked, the hotel employees rushed her to the hospital. When she felt better, she traveled with the kids to London, then later to Texas. She said, “I thought the boys would have better opportunities in America.”

Tania Joya tells this story while sitting at a trendy wine bar on a street lined with glittery shops and cafes in Plano, where she now lives. In a sleeveless top, denim skirt, and suede heels, her hair casually tousled, she is a world away from her life in radical jihad. She takes a sip of sparkling white wine, dips a pear slice into a creamy cheese fondue. Couples stroll by on the sidewalk, disappearing into bars and restaurants at dusk. “When I look back, it all feels like a bad dream,” she says.

Her transition to Texas in late 2013 was not easy. Despite being free, and living in a safe home with her in-laws, she felt alone. “I thought, ‘Who am I without John?’ My identity was his identity,” she says. He wrote to her, trying to persuade her to come back to Syria. But she wanted a new life. “I told him, ‘I’m moving on,’ ” she says. She gave birth to their fourth son and legally divorced her husband, shedding his last name. When she learned her former husband had taken another wife, she cut off all ties, she says, noting, “I don’t know if he’s alive.”

And then, she unwound. Free to think on her own, she began working on deradicalizing herself, continuing the thoughts of escaping extremism that had been brewing for years. “I stopped thinking in terms of destiny, that everything is preordained. I thought about how I have control over my own life. I have control over my own body,” she says. “I read about philosophy, existentialism. I thought about American values and freedoms. I thought about how unhappy I had been, trying to be someone I wasn’t, longing to be myself and live the way I wanted to. I thought about how women are pressured to cover themselves, but men aren’t pressured to control themselves. It didn’t make sense. God made me look the way I am, but I had to view it as a sin.”

For Tania, the shift away from extremism began with her children and wanting to keep them safe. Now she is thinking about the future and how she can use her experience to help others. She would like to work in counterterrorism, prevention, and deradicalization. “I want to help people avoid this fate,” she says. “I believe prevention is the most humane way to counter terrorism. I’d like to build a career helping with prevention and deradicalization programs, whether it’s Islamic or white nationalism.” To that end, she is taking online college courses in a range of topics, including counterterrorism, human rights, and global diplomacy. “I feel very driven,” she says. “I lost years of my life in my twenties.”

Wandering through a favorite shop in Plano one recent afternoon, she admires the colorful Turkish lanterns hanging overhead, then lingers over the scented soaps. She likes this place because it reminds her of the home she had in Cairo. As usual, she had to abandon everything when they left. “Every home I decorated, we had to leave,” she says, recalling how her husband would dismiss her desire for a comfortable home, admonishing her, “It’s just possessions.” She chats with the shopkeeper, promising to come back one day to furnish her own place.

Later, at her favorite Indian restaurant in Plano, she sits with an array of spicy dishes spread out before her—chicken tikka masala, lamb with lentils, paneer with peas. “I come here at least once a week,” she says. Then she declares, “I love America. I feel very fortunate.” Riding home through the leafy, pristine streets of the suburb, she points to another favorite place: the hair salon. She jokes that she has years of beauty treatments to catch up on, having covered herself for so long. At her home, an apartment of her own in a modern subdivision awash in fuchsia flowers, she sinks into a beige sofa in the living room. Photos of her four sons hang on the wall, along with a flat-screen TV. A bookshelf is lined with tomes about history and politics, with an Elmo doll on the top shelf. Snapping open a can of fizzy water, she scrolls through her Facebook page, clicking on photos of her former husband and the boys as they grew up. In one, her husband lies on his back, smiling, holding one of his young sons in the air.

As Tania gradually settled into life in Texas, she craved companionship, so she posted a profile on Match.com. “It was the first time I’d ever dated,” she says, smiling as she recalls the dating-unfriendly things she wrote in her profile. “I wanted to be honest. So I said I have four kids. I said I’m looking for security. I said my husband had gone off to be the next Osama bin Laden.” Nonetheless, she says she got a whopping 1,300 replies, and the site congratulated her for being one of the top ten most viewed profiles of the month. “I was like an alien when it came to dating,” she says. “I had always thought arranged marriage was good. Why date for more than three months?” She went on a few dates, navigating a new world. “I’d never been exposed to alcohol,” she says. “Men would try to get me drunk.”

When Craig Burma came across her dating profile, he was intrigued. He thought she must have a good story to tell. Handsome and gregarious, with light brown hair and a big smile, he sits at her dining room table on a recent Saturday morning, describing their first date. “She was beautiful, lovely, but I wanted to learn her story,” he says. “I wanted to understand.” When she told him about her past, he says, “I thought it showed her strength. She had faced such adversity.” The two talked for hours that night over tapas at a Spanish restaurant. “She was making me try new things, like shark and octopus.” He was so taken with her, he says, “I would’ve eaten a piece of cardboard.” She was impressed by his curiosity about the world. “I thought he was really smart and interesting,” she says, recalling how he talked about social movements such as Occupy Wall Street. “I’m crazy about smart people,” she says. “There’s nothing sexier than a good conversation.”

“I feel very driven. I lost years of my life in my twenties.”

Now they are engaged to be married. She wears a diamond ring, and the two laugh about her tiny ring finger. Craig, a director at a print and marketing solutions company, says, “I just love her like nobody’s business.” They attend the Unitarian Universalist Church, an inclusive religion that draws people of all faiths. “It’s all about a progressive message,” she says, noting that the church quotes texts from many religions and spiritual figures, including Mother Teresa, Rumi, and Christ. In her spare time, she dances to hip-hop videos to stay fit. Her fiancé has helped her financially as she gets on her feet. “The happiness that I was craving so badly in my first marriage, I found it in Craig,” she says. “I’d never had anyone say, ‘You can do it.’ I’d never had that kind of support from anyone. I’m very fortunate. My kids are healthy, safe, and happy. Their life is good. They’re very privileged to be in America.”

As for Yahya, he’s gone on to become the leading producer of English-language propaganda for ISIS, according to Wood, helping to recruit fighters with his words. Meanwhile, Tania is doing just the opposite, hoping to help keep others from following her ex-husband’s path to radicalism.

On a Friday afternoon in August, Tania’s four sons burst in the door, all smiles and energy. But when they see their mom talking to a reporter, they’re suddenly nervous and shy. They disappear into another room, unsure if reporters can be trusted. The older ones have heard President Trump disparaging the press on TV. Tania sits them down on the sofa and explains what journalists do. She advises them to keep an open mind, to always get the facts before forming an opinion, and to not let others tell them what to think. They listen and agree, nodding. “Don’t become extreme in your thinking,” she says. “Look what it did to your father.”

Abigail Pesta is a New York–based journalist and author who has written for the Wall Street Journal, Cosmopolitan, the New York Times, Marie Claire, Newsweek, and many others.