On January 27, 2017, President Donald Trump signed an executive order on immigration that caused great confusion and uncertainty in its wake. The order stipulated the following: there would be a ninety-day suspension of the issuance of visas to immigrants and travelers from Iraq, Syria, Sudan, Iran, Somalia, Libya, and Yemen; a 120-day suspension of the federal refugee resettlement program; and the resettlement program would be capped at admitting 50,000 refugees, a reduction by more than half of what the Obama administration had agreed to for 2017. Pushback was immediate, and protests erupted at airports across the country, including in Texas.

Yet before President Trump’s executive order, Texas was grappling with its own questions around refugee resettlement. In September, Governor Greg Abbott withdrew the state from the federal refugee resettlement program—a secession that went into effect on January 31, 2017—because, he said, the federal government could not guarantee that refugees admitted to the state would pose no security threat. This followed an unsuccessful attempt by Abbott to block the arrival of Syrian refugees into Texas. For now, though, the withdrawal has been rendered moot: no refugees will enter either the state or the country for at least the next four months, and the president’s executive order includes an indefinite prohibition of entry by Syrian refugees.

Perhaps lost in the politics surrounding Syrian refugees is that these are individual human lives that have been shattered by civil war and extreme disruption. That these are people trying to reconstitute their lives here in America—and more specifically, in Texas, which has one of the largest refugee populations in the nation. What follows is a series of six profiles of Syrian refugees and those who are helping them resettle in southwest Houston. These stories are an attempt to draw a more nuanced picture of refugees than our divisive politics so often allow for.

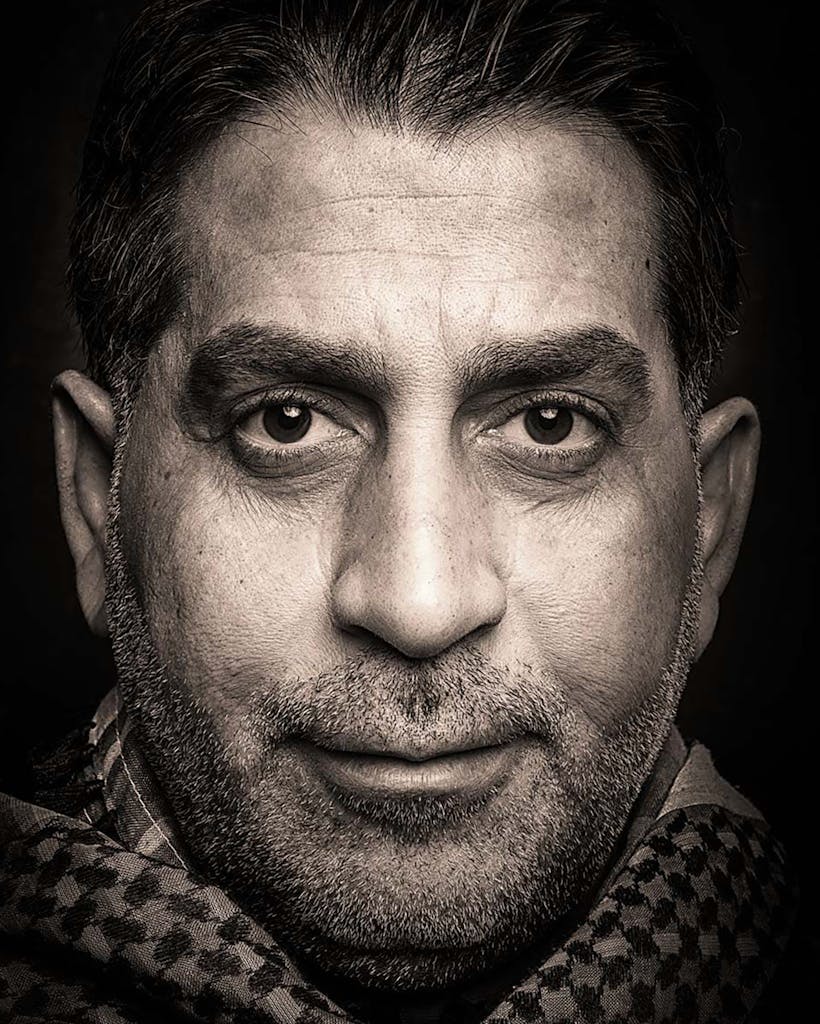

Ali Al Sudani

It might have happened another way, but it didn’t. Or it might not have happened at all, but it did. The brother of his friend might not have fallen sick in April 2003, that first week or two after the invasion of Iraq. Ali Al Sudani might not have heard the phone call. His friend might have brought his brother to a different hospital, not the one being held by British coalition troops. It was purely by chance that, when Ali’s friend asked him to please come translate, Ali was available to go.

And even then, the British soldiers might not have realized they needed Ali. They might have let him disappear back into the foreign city whose signs they could not read. But the soldiers asked him to stay. They understood they needed translators to convert the chaos of the war’s aftermath into words, even though he was an engineer, just starting out after his university studies, not a translator at all. Ali had never even spoken English outside of his classes.

The Iraq War, and that chance encounter at the hospital, led Ali towards a life he could never have envisioned back in Saddam Hussein’s Iraq. A life in Houston, where the 43-year-old serves as Director of Refugee Services for Interfaith Ministries, translating that sprawling city of opportunity and desperation for strangers in a strange land. It’s a life that feels like the one he was always supposed to have lived.

Ali grew up in Maysan Province, a flat landscape of marshes that, to the east towards Iran, gave way to undulating green hills. He was a city boy, from Amarah, north of Basra, and part of a generation that has often been called “The War Children.” As a boy, he lived through the Iran-Iraq War of the eighties. Then, after the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, came the Gulf War in the early nineties, when Ali was in high school. In the chaos of Iraq’s defeat by the American-led coalition in 1991, as the demoralized troops withdrew, the people thought they saw their chance and rose up—Kurds in the north, Shia in the south, along with rebels from a mix of ethnic and religious and political backgrounds. But, Ali recalls, understatedly, the uprisings didn’t go well. Just a month after they started, they were brutally suppressed by the Iraqi Republican Guard. A dozen years later, the Iraq War began.

Through all of these wars during Ali’s formative years, Saddam Hussein simultaneously waged a relentless battle of oppression against his own citizens. Iraqis never knew if something they might say would be used against them. Two of Ali’s cousins were executed for their left-leaning politics and their communist sympathies, which in Iraq mainly meant fighting for basic freedoms and for the middle class. And so when the Americans and the British arrived in 2003 to oust Saddam, Ali believed in the cause of the coalition forces. Civil society in Iraq under the regime was as barren as the Arabian desert, but once the dictator was captured and executed, NGOs intent on building the civic sector sprang up like oases. Ali believed in the work he was doing. He wanted to help bring democracy to his country and to educate the foreign troops. So Ali worked first as a translator, then later as a project manager for an NGO run by the Czechs. And it was through the Czechs that, in 2007, he moved to Jordan to manage Iraqi NGOs and nonprofits from there.

Because, by that point, his position in Iraq had grown treacherous. He’d been marked by his work for the Coalition Provisional Authority, the transitional government in Iraq formed by its occupying forces: mainly the U.S. and the U.K., as well as Austria and Poland. Friends—teachers and journalists and other translators—were being assassinated. It was never clear why, or who would be next, or when they’d be taken. Ali had been receiving letters at the local office warning him to quit or face the consequences for his work implementing the strategies of the “collaborators.”

In Jordan, he finally realized: there was no way back home. No way back to the marshland of Maysan, to his brothers and sisters, to the life as an engineer that he’d once imagined for himself. So he registered with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and was granted refugee status in Jordan, his country of first asylum, which gave him certain protections and basic human rights as he waited to find out whether he would be stranded in Jordan, or permanently resettled in another country.

But this status as a refugee also placed him in a precarious limbo. As a refugee in Jordan, he could not get a driver’s license or a bank account. Nor, technically, could he work for the Czech NGO, though he did anyway. This unsettled status haunted him. Once, his team was helping to train elected officials from Iraq—members of parliament and civil servants who had been invited to tour the Wihdat Refugee Camp in East Amman, and the palace of Prince Hassan, brother of King Hussein of Jordan—and Ali kept waiting for someone to ask for ID. He was doing nothing morally wrong, but he was working illegally and he knew it. He lived under the relentless fear of one day being found out and deported.

Back then it took a year for the bureaucratic process of permanent resettlement to unfold. Now it’s at least double that: individuals must submit to a rigorous vetting process, one that might change in response to President Donald Trump’s January 27 executive order. But for Ali, it was a year of telling his story and presenting those threatening letters and trying to explain why there was no way back home, first to the UNHCR, then—after the multiple fingerprint screenings and the photographs, after the background checks and interviews with the State Department, the Department of Defense, the Department of Homeland Security—to the officer with US Citizenship and Immigration Services. After all of this, suddenly, one April day in 2009, he was in Houston, alone and lonely, trying to navigate the wide highways.

Ali’s definition of refugees is very simple. Refugees, he says, are normal people in abnormal circumstances. A corollary to this definition: refugees have fled from the cultures that shaped them because of war or persecution—and typically they flee because they have to, not because they want to leave their homeland. The subtext to both definition and corollary: any one of us can become refugees. That is, says Ali, just the nature of the world in which we live.

But he also believes that it is the nature of human beings to want to help others. And I was a stranger and you welcomed me, he likes to quote from the Gospel of Matthew. This verse, he says, makes clear the through line that tethers Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—all three Abrahamic faiths that exist in such tension in many places today. Perhaps that requirement to welcome the stranger is itself grounded in a recognition of the nature of the world and our tenuous human position in it: There but for the grace of God go I. At any rate, this welcoming of immigrants and refugees is really the characteristic that makes America great, Ali thinks—not the fact that we have the world’s strongest military or the most advanced democracy. We have open arms, he says, and big hearts.

And they have been put to good use, particularly of late to help ease vast dislocation across the globe, a grim fact that statistics bear out. According to the UNHCR, the world is now witnessing the highest levels of displacement ever recorded. By the end of 2015—the latest numbers available—65.3 million people had been forced from their homes. The majority remain internally displaced within their own countries. And 21.3 million of the displaced have crossed an international border and applied for and been granted refugee status. Most refugees will remain in that first country to which they fled, all the while hoping that one day they can return home. But the most vulnerable among them—those, like Ali, who realize there is no way back and can prove it—are permanently resettled in a third country.

Permanent resettlement is actually the last, desperate resort. Though only accounting for a fraction of the total of the millions displaced, the United States permanently resettles more refugees than any other country. In recent years, it has capped admission at 70,000, but in 2016, it took in 85,000 refugees—8,300 of whom came to Texas. For fiscal year 2017, President Obama had authorized the U.S. Refugee Program to accept up to 110,000 refugees. But under President Trump’s new executive order, the ceiling is 50,000. The order suspends the federal resettlement program for 120 days; Syrian refugees will be banned indefinitely.

But up until now, at least, in recent years Houston has taken in more refugees than any other U.S. city except San Diego. In 2016, that number was 2,248. They come from roughly fifty countries, including Cuba, Iraq, Afghanistan, Congo, Burma, Somalia, Bhutan, Ethiopia, and, increasingly, from Syria, whose civil war has spawned an appalling and almost incomprehensible 4.8 million refugees—roughly the entire population of Harris County. And yet only about 300 Syrians came to Houston this past year—about the number of diners on any given night at one of the city’s hip Inner Loop restaurants.

Assigned to one of five refugee resettlement agencies in the city—including Interfaith Ministries, whose staff of 28 have themselves arrived here from ten different countries—the refugees are flown to America with the help of a loan for their airline tickets that they must pay back. Once in the U.S., the federal refugee resettlement program gives them cash assistance to pay for their furnished apartments and food, as well as Medicaid. Caseworkers go with them to get their immunizations and to enroll their children in schools and to apply for Social Security cards. They advise them on finding jobs. They encourage them to take English classes. After a year, refugees can apply for a Green Card to become Permanent Legal Residents. After five years, they are eligible for citizenship. But all that they are given comes at a price: within six months, the refugees are expected to be self-sufficient. From nothing—often not even English, and, in the case of Arabic-speakers, not even the same alphabet—to on their feet in about six months.

Ali fiercely defends this program, whose fundamental goal is to save lives, though he recognizes the stress it can place on refugees. Nothing is free here, he reminds, and refugees are not babies. They must choose to work hard. But they have both the legal status to do so, and a clear path to citizenship. This system, he maintains, exists nowhere else in the world. And because America has an infrastructure in place to welcome refugees, they aspire to invest, they aspire to participate in civic life, they aspire to call this place home. It’s about inclusion—not exclusion. And Ali thinks that because of this inclusion, and because of the diversity of languages and nationalities already here, refugees quickly gain a sense of belonging that has critical consequences. We don’t have isolated communities, he points out. We don’t have radicalized communities. We might have radicalized individuals—that’s just inevitable. But unlike many European cities, or countries like Jordan or Turkey, this push toward assimilation saves the U.S from the kind of large-scale terrorist attacks that Europe has suffered in recent years.

Up until President Trump issued his executive order, the resettlement agencies of Texas were already grappling with the repercussions of Governor Greg Abbott’s decision last fall to pull the state of Texas out of the federal Refugee Resettlement Program beginning on January 31, 2017. The federal government channels funding to the states, which distribute the monies to local resettlement agencies like Interfaith Ministries. But Governor Abbott no longer wants the state to act as middleman, ostensibly because the U.S. Office of Refugee Resettlement could not absolutely guarantee that refugees posed no threat to the security of Texas. Abbott’s reason for withdrawing, in this vicious political era, seemed tied to President Trump’s charge during the campaign that Syrian refugees—and Muslim refugees more broadly—despite their intensive screening, despite their immense need—could be a Trojan horse for terrorists.

For Ali, to have Texas pull out of the federal refugee resettlement program poses a possible existential threat. In 2016, the state resettled more refugees than any other. As a Texan, as a Houstonian, when Ali attends national conferences, or when he travels abroad, when he meets with other resettlement agencies and other nonprofits involved in resettlement work, he feels proud to be doing so much, to be part of this great cause. He likes challenging the perceptions people often have of the Lone Star cowboy state with the truth: that Texas has a rich history of welcoming refugees, that Houston is one of the most diverse cities in the world. But with the state refusing to welcome the strangers among us, Ali’s beliefs could be undermined.

Still, because the Refugee Resettlement Program is a federal program, refugees—when the program resumes—will still arrive at airports across the state to be greeted by caseworkers and volunteers with balloons and stuffed animals. Texas will no longer manage the program, but the program will go on. The state has been divided into four regions, each with a local resettlement agency acting as the fiscal manager to distribute and oversee the use of federal funds. In Houston, it’s the YMCA. In Austin and San Antonio it’s Refugee Services of Texas. In Dallas it’s Catholic Charities. In West Texas it’s the International Rescue Committee.

That reconfiguring had already meant a huge upheaval. Now the resettlement agencies must absorb the implications of Trump’s executive order. For the next four months at least they will not receive any new refugees, nor the funding to resettle them. Ali hopes that with the support of the community and their donor bases, Interfaith Ministries and the other resettlement agencies can maintain the infrastructure they have in place.

But even in this hour of uncertainty, Ali believes in the American people and in the values that are protected by the constitution, values he traces back to this country’s founding. He recalls George Washington’s letter, written on December 2, 1783 to the “Members of the volunteer Associations & other Inhabitants of the Kingdom of Ireland who have lately arrived in the City of New York”: “The bosom of America is open to receive not only the opulent & respectable Stranger, but the oppressed & persecuted of all Nations & Religions; whom we shall welcome to a participation of all our rights & privileges, if by decency & propriety of conduct they appear to merit the enjoyment.”

The U.S. Refugee Resettlement Program aligns with this fundamental condition of the American character. We should, Ali says, prioritize admittance to the U.S. on the basis of humanitarian need, and not discriminate against a religious faith, as Trump’s indefinite ban on Syrian refugees and his temporary ban on travel from seven other Muslim-majority countries implies. Historically, Ali insists, the U.S. has always taken in those victims of the most dire crises: Vietnamese, Cambodians, Bosnians, Rwandans, Congolese, Sudanese, now Syrians. And he worries that Trump’s executive order sends the wrong message about this country, that it will undermine our moral standing in the world.

The Al Salih Family

It was early June and they had been here two weeks and now they all had Band-Aids on their upper arms from the immunizations that their caseworker from Interfaith Ministers had taken them to get. The three lanky boys—Wael, who is twelve, Yazan, ten, and Amir, four—wanted to go outside, but Rania, their mother, was worried about them in the heat, so instead they had to content themselves with playing games on the cell phone they passed between them. But sometimes their pent-up energy burst out in frustrated spasms. There were no toys. There was not much of anything in the apartment, really, other than a black faux-leather armless sofa and standing lamp with frosted shade and oak table and chairs in the kitchen. The laminate wood flooring stretched out down the hallway to the bedrooms.

Like her teenage daughter, Maia, Rania’s voice was lilting, her skin fair and everything about her rounded, even the enormous copper-colored chrysanthemum-shaped bow at the back of her head. Her husband, Mohamed, was her opposite: dark hair shaved close, skin the color of olivewood. There was nothing extra about him, and the way he held himself, he appeared coiled, ready to spring into action. His eyes were open and eager, sometimes pleading. He seemed intent on conveying the impression that he was holding it all together. But the family had no car and they knew no English other than “My name is . . .” and “Welcome”—the latter a revealing insight into the culture from which they come. Mohamed confessed that he didn’t even know his own address, and he knew how helpless this made him.

They were from Homs originally, which came under siege by the Syrian army beginning in May 2011—early in the war. During the protests in the main square, they stayed home, shut inside, afraid of even looking out of the window. At night there was often shooting. Then checkpoints starting popping up throughout the city, and tanks planted themselves at the ends of streets, including their own. The men in those tanks fired on protestors, inevitably catching bystanders in the crossfire. The family would often stay inside for days until finally, out of hunger, Mohamed would go out to buy bread. They grew accustomed to seeing bodies piled in the backs of Suzuki flatbed trucks. But sometimes bodies would lie in the streets with no one daring to collect them. And Maia remembers the day in fourth grade that she was leaving school, walking out the narrow door into the sunlight of the afternoon with her friend, a Christian, when two white cars pulled up and men leaped out and started shooting. Behind her, she turned to see other kids trying to get through the narrow door, the only exit, and then the explosions. Most of her friends died. That image of the door stays with her.

One night, with fighting all around them and fleeing neighbors urging them to leave, the family drove north from Homs to Aleppo, Rania in her pajamas, trying to wrap Amir, who was just a baby, in the thin nightclothes she was wearing. In Aleppo, they stayed in the neighborhood of Sayf Al-Dawla for seven or eight months, until one night the earlier scene was repeated: neighbors in pick-up trucks pulling them in to the open bed, planes overhead dropping bombs on houses and buildings, snipers. They made it to a more secure area of the city, but soon after, they departed Aleppo all together.

They returned to the countryside near Homs where Rania’s family was living. But even here they were not safe: Wael, out buying bread with Mohamed, was struck in his foot by shrapnel. He was eight. Another day, Mohamed stood with his children and watched a bomb strike a nearby building. That’s when they applied for passports.

Some time in 2012—no one can remember exactly when—they made their way south, along with thousands of other Syrians, where they were stopped at the Jordanian border. Stranded in a kind of no-man’s land for a week, by the third day they ran out of food and were drinking Pepsi, the only item left at the only supermarket accessible. They slept on the stairs of a hotel at night, which was better than being on the street. But even there on the stairs, they were vulnerable. The tanks would come and solders in their uniforms, speaking in the distinguishing Alawite accent of the regime, would stream out, trolling for girls. Rania had to pile blankets and bags over Maia to hide her. Rania somehow convinced a bus driver to get them across the border into Jordan, which he somehow did. They had nothing left. Rania remembers with gratitude how the Jordanian police took the jackets from their own backs to cover them, and also how they fed them.

For four years they lived in Zarqa, a city abutting Amman in the north of Jordan, not far from the Syrian border. Four precarious years of trying to work undetected—delivering gas canisters, in construction. Once, Mohamed, who had a source for wholesale cleaning supplies, spread out his wares on a cloth to sell on the street. Some of his boys were with him. A policeman passed by and asked for his authorization. When Mohamed could not produce the proper documents, the policeman told him, “One of your neighbors has complained because you are cutting into his business.” Mohamed replied, “I know. But I have to.” He gathered his supplies and started to send the boys home and prepared to be arrested and then, most likely, deported back to Syria. This had happened to an uncle of his already, and now his aunt was stuck in Jordan alone with six children. But Mohamed got lucky: the Jordanian cop noticed his kids, took pity on them all, and let Mohamed go.

The Al Salih family had registered as refugees when they entered Jordan, and, over the years, they filled out papers and sat through interviews and waited. Twice, they say, the IOM, the International Office of Migration, offered them permanent resettlement in Europe, and twice they refused. But finally, they were offered a place in the United States. By June 2016, the family was in Houston, in an apartment on the Southwest side of town with other Syrians who had been here since the previous fall. School would start in August.

Towards the end of Ramadan in July, Rania met a woman at Walmart—an American married to a Syrian. The couple invited the Al Salihs over for dinner, where the kids swam in their pool. Days later, the woman called to ask if Mohamed had a driver’s license. Then they gave the Al Salihs a used station wagon so that Mohamed would have transportation. The couple also gave them furnishings—a plush sectional sofa with throw pillows, muted prints of daylilies and peonies, a rug to soften the laminate floor, drapes for the living room window. By now there was also a television, running most of the time with cartoons in Arabic.

Mohamed and Rania knew that they needed to learn English. Actually, as Arabic speakers, they first needed to learn the English alphabet. But the classes seemed so inaccessible. They had heard that they could get free lessons at the community center around the corner from their apartment, but those wouldn’t start until the fall. Same with English classes for parents that the Alief Independent School District offered at all of its campuses. Another organization, the Bilingual Education Institute, extended classes free of charge to refugees for up to five years and often would set up shop in or near apartment complexes where refugees were being resettled, but BEI had no plans to teach in the vicinity of the Al Salihs. Now that they had a car, they could conceivably travel the ten miles to BEI’s main office, but when they were gone, who would watch over the children and make sure they were safe?

Mohamed was also anxious to start working. He felt he was wasting time, and he didn’t want to sit and do nothing. His employment authorization card would be ready soon, but in the meantime, he had managed to get a little work with a halal slaughterhouse as Eid approached, when Muslims across the city were preparing for the feast that would mark the end of the month of fasting, and when those who could would donate meat to the poor. But they didn’t need him full-time. He had also found a job at a gas station where the owner was willing to hire him. But then the owner realized Mohamed didn’t speak any English and he had to back away from the offer.

Still, they were feeling hopeful. When Rania talked to friends and family stuck in Jordan, they told her that in the United States, they would be respected. In Zarqa, kids had made fun of her children because they were refugees, and treated them as if they were less than them. But here, she sensed, refugee children are part of society. Here, her children have rights. “Now I realize how much America cares about children,” she said. “Thank God I’m here. Alhamdulillah.” And Mohamed recalled, “Before the Revolution, when I would talk to my children, I would ask them, ‘What do you want to be when you grow up?’ And they would say, ‘A doctor.’ And I would joke with them, ‘You will be a doctor. You will travel to America.’ ” Traveling to America represented, in Mohamed’s mind, the most improbable dream. “For a long time,” he went on, “we forgot about our dreams. But now God has brought us to this country where dreams can come true.”

By early October, they were all beginning to feel trapped. Back in Syria, Maia would often stop by Mohamed’s shop after school. In Jordan, when they were bored, they would take a bus to the souk, the marketplace in the city center of Zarqa. But here, in Houston, there was no center, nowhere to go. Sometimes they stood around in the parking lot of the apartment—“like weirdos,” said Maia. Sometimes they drove to Walmart, just to get out. But Rania wanted to really explore. She wanted to get to know this country. And beyond all of this, they were frustrated by a deeper kind of confinement. They had no money. When they needed something, they had to hope someone would come to them and offer it somehow.

“Have you found a job?” their caseworker from Interfaith Ministries had been asking Mohamed. Time was starting to run out. Their resettlement aid would end in less than two months. Now that the kids were all in school, the couple would drive around during the day looking for work for Mohamed: Middle Eastern stores, Pakistani stores, warehouses and factories. Some said that they’d call back if they had openings. Some said that if Mohamed had even a little bit of English they could hire him. “All I do is think about money and what will happen, how I can pay,” Mohamed said. He would, he said, push carts through the parking lot at Walmart for $6—even $5—an hour. He wanted to work with his own blood and sweat. He didn’t want anyone to pay for what he himself had to do.

The stress and the uncertainty were taking a toll. Though they’d always make up, Mohamed and Rania were fighting. Then one week, Mohamed went to the hospital with pain in his left shoulder, above his heart, and the doctors told him this was because of anxiety and sadness. Rania had high blood pressure and was on medication. When the doctors directed her to a therapist, Rania’s friends told her not to go. They said that if authorities found out, they might take away her children. But talking about her time here so far had been a comfort. And Rania was taking English at Amir’s school. When she missed two classes because of her health, the teacher, a woman from Sudan, enclosed Rania’s face in her hands and asked, “Are you sad? Are you depressed?” That, too, had been a comfort.

Mohammed, though, wasn’t going to the classes. How could he spare time from looking for work? But he still couldn’t write his name in English. Now that Maia knew a little bit of the language, he imagined that she could teach him some day. When Maia first started at the middle school, she felt like a deaf person at a symphony. The kids would talk to her but she didn’t know what they were saying. She had no one. She hated going to school, and she would come home and cry. For the first couple of weeks she was placed in a regular classroom because her parents couldn’t read the paper the school sent home, asking for permission to put her with other ESL students. But now she was where she was supposed to be, and she was happy. She was picking up English quickly, even if she still struggled to speak it herself, and the teachers sometimes even asked her to translate for her neighbor, Mahmoud, who was in her class.

Maia hoped that someday she would reach the point where she didn’t want to leave America. Mohamed said that it had always been his dream to send one of his children to America for an education. “Now,” he said, “I just dream of getting a job pushing carts.”

By early November, Mohamed had found a job. So had Rania. He was working five- and six-hour night shifts at a collision repair company and making $8 an hour. Rania was cooking and doing light housekeeping from time to time for a woman from the Emirates and her husband, a sheik. They were in Houston, staying near the Medical Center, while their daughter underwent treatment for cancer. They sent a driver in a Mercedes Benz to pick Rania up.

The Al Salihs had a new coffee table and several silk flower arrangements. But their rent was $1,400. And electricity, with the heat in Houston that seemed to never subside, was $250. There was gas, too, that the car ate up. And the other day the apartment complex fined them $50 for letting the boys run free through the parking lot. In a few months, their Medicaid will end. Interfaith Ministries had to help out with rent again this month, even though their aid had technically expired.

“One day I will tell you all of my sorrows,” Mohamed said. “There is relief in telling.”

Nama and Musa

They fled from a nightmare into another nightmare. In Jordan, just across the border from Syria, Nama could see the shelling in her homeland, but still she wanted to go back. A force was pushing her away, though, away from her siblings and her parents, pushing her when she had no will to move. She wanted to stay with her children and die with her family, stay in that land back across the border, among Syria’s low, grassy hills of the Golan. But her husband would have died if they had stayed. Musa was suffering from cirrhosis. Though a good practicing Muslim, one who abstained from alcohol, the disease had found him nevertheless. Now it was turning his liver to scar tissue. And so, hoping for a transplant, hoping for the care he wasn’t getting in Jordan, last September they came to the United States.

Before the nightmare began, Nama and Musa*, both now in their early thirties, had lived in a suburb of Damascus. Over the years that they were married, they added on to their small, three-room house to accommodate their growing family and his parents, who lived with them. He had his tailoring business in front. She had chickens and a cow and a garden. She taught at the elementary school, and Musa’s mother would be there to take care of the children until Nama got home. Every day, friends and family would visit and sit and talk over sweet tea in the formal living room with its overstuffed couches and low tables. When Nama thinks about her house, she doesn’t miss the building itself, only the gatherings and the people who were always there. Later, after they’d fled from the nightmare of the Syrian civil war, they heard that the house was burned.

The good thing about life in Syria before the war was that it was safe. People had what they needed. But no one was really happy. They thought of the country as a stable: There was food. There was water. People were living—but without ambition. Would you really call that a life? Bashar al-Assad was a dictator, an Alawite, a sect within the Shia branch of Islam, who refused to appease the people, people he never thought would rise up. After him, his son would take over. The regime would reign forever. And once the protests started, sure, Nama and Musa wanted Assad to leave, they wanted freedom, but not with such bloodshed. If they could choose now between the status quo of their previous life and what happened after the uprisings, they would choose the status quo.

Just weeks after the leaders of Egypt and Tunisia had been ousted, and as Libya was beginning to fall too, some teenagers in Daraa had scrawled “It’s your turn, doctor,” with red spray paint on a wall of a school in March of 2011. They were addressing Assad, who is an optometrist. In the popular imagination, this taunting phrase on the wall (which rhymes in Arabic) is where it began. Boys in the neighborhood were rounded up and tortured. In Nama and Musa’s telling, when the fathers and mothers and other friends and relatives went to demand their release, the women’s headcovers were taken from them. Police security forces gestured to the mothers in the crowd and told the gathered men, “We’ll help them have more children.” In reaction, protests erupted and spread from city to city.

Early on, it was a shock to see that people could rise up out of the fear that had gripped them for generations. Musa thinks that the Revolution was started by young kids because they had not lived through the actual horrors their fathers and grandfathers experienced, like the massacres in the early eighties in response to Sunni opposition from groups like the Muslim Brotherhood. The older men did not want the Revolution to happen. They would lock the house from one side, but their sons and grandsons would go out the other door.

The Assad government proved unrelenting and unforgiving. It looked to annihilate any bravery in anyone in any way. Small protests in one street would lead to the Syrian army storming houses and slaughtering civilians within a wide circumference from that epicenter—communal punishments, which led to communal fear. In Damascus, Musa remembers how, at the funeral for a man murdered by the regime, as mourners bore the casket on their shoulders while others followed behind, walking in communion to the cemetery, the regime opened fire. By the end, seven hundred lay dead. In a YouTube video of the aftermath of the massacre, relatives cover and uncover the mutilated bodies with blankets. Do you see? They seem to say in disbelief themselves. Do you see this atrocity? The bodies of the adults are wrapped in white. Children in pink.

In late 2012, the fear eventually found Nama and Musa too. When the regime broke in to the suburb next to theirs, they suddenly sensed that the advance would swallow them up. Musa took two of their five children and drove south to their hometown of Quneitra in the Golan Heights, near the border with Israel and Jordan. Nama followed with the rest of the children, the youngest a baby. They thought they would be able to return home later to collect the things they left behind. But neighbors told Nama that the day after they fled, the regime forces broke through and slaughtered everyone who had stayed. Since that time, they say, no one has been allowed back in. Government forces have systematically cleansed their neighborhood of Sunnis and filled it with Shiites. The few original inhabitants who remain are members of the regime.

They were in Quneitra eight months. Musa often had to move from home to home, aided by neighbors—friends and family alike—to avoid the regime forces looking for men to press into service on the front lines as human shields. Sometimes he would have to hide out in the fields outside of the town. Nama would bring him food. Sometimes, too, he would have to make the journey down to Daraa for medication, passing through military checkpoints like minefields, vulnerable to capture or imprisonment. Once, at a cousin’s house in Quneitra, security forces arrived and began collecting the men’s IDs. Everyone knew what was coming. But Musa had an idea. “We are about to have breakfast,” he told the soldiers. “Why not join us?” And they did. He told them, “I’m a sick man. I don’t have anything to do with what’s happening.” For some reason, after eating, they returned the IDs. Afterwards, Musa said, “That’s it. I’m leaving.” And he and Nama drove across the southern border into Jordan with nothing but their kids. That was in mid-2013, just before Jordan closed its border crossings, as it has done intermittently since.

They had no choice but to go to the Zaatari Refugee Camp and to formally register there as refugees. But the conditions in the camp, they say, were deplorable. (Others have echoed this.) Nama kept beseeching Musa, “Why did you bring us here?” She thought it would have been better to die in Syria. Four days after arriving with nothing, they left the camp without authorization from Jordan, which was struggling to absorb and keep track of the overwhelming influx of Syrians. Refugees who wanted to leave were supposed to prove they had a sponsor in the country and to pay a “bailout” fee. But instead, in the darkness of night, the family went out walking. Nama had a cousin in nearby Irbid who had come the year before and who sympathized with them. This cousin helped Nama pass the children through the wire fencing and into a waiting car. Musa, too sick to be of use, had gone ahead alone.

Because they had moved out of the refugee camp and into the city without official permission, for two-and-a-half years, they lived in fear of being caught and sent back to Zaatari, or to another camp out in the desert. Still, Nama never thought of leaving Jordan. Being refugees, they couldn’t work—for a Syrian to obtain a work permit in Jordan is nearly impossible. But their children were in school and a net of friends and relatives and international aid agencies held them up, paying for their rent and food. And Syria was still so near, just across the border. But the doctors were saying Musa would need a liver transplant, and in late 2014, the government of Jordan ended its policy of free health care services for refugees. After that, the question of Musa’s condition hung over them like a specter.

They arrived in Houston in September 2015, after all of the paperwork and the interviews and the background checks and the cultural orientation classes had been completed through the International Office of Migration back in Jordan. After the State Department and its US resettlement agencies had determined the city to which they’d be sent. After Catholic Charities, the local resettlement agency to which they’d been assigned, had furnished and provisioned an apartment. After their caseworker had picked them up from the airport. After Jordan, where they knew the language and the topography, the sprawling city felt like the middle of nowhere, with no place to go and no one to turn to and no one who seemed to know they were there.

The apartment complex on the southwest side of the city, off an artery off a highway, past auto body shops and a Chick-Fil-A and a football stadium and a high school, is like a small English village filtered through a seventies suburban lens: mansard roofs and black shutters and faux-half-timbered walls, some with second-floor alcoves jutting out over the pebbled concrete sidewalks. In the early, dream-like days when there was only one other Syrian family in the complex, Nama would escape her sense of dislocation by sleeping from sunset until dawn. A man they didn’t know showed up once with a washing machine and supplies. They never saw him again. A neighbor below would always greet them sweetly and smile at the children. When their drying laundry fell onto her patio, she would wash it and fold it and send it back up.

Though Catholic Charities was helping them with many of the fundamentals, more informal outfits filled in crucial gaps. The Syrian American Club began to organize gatherings for the refugees who were seeping in—crafts for the kids, advice for the adults. A free-agent volunteer named Carmen Garcia, herself a Mexican-American convert to Islam, helped organize English classes for Nama and Musa in their apartment. She also got a car donated and found Nama a job at Sult’an Pepper in the mall washing dishes and prepping vegetables. Another woman, a friend of Carmen’s, hired Nama to teach a children’s class at a nearby mosque on the weekends.

But they have not been able to do what they’ve been asked to do to support themselves. “From our earth, we live. From our job, we live,” Nama says of life back in Syria. But now that self-sufficiency is gone. It’s impossible for Musa to work and he has letters from his doctors here to prove it, but so far he’s been denied Disability Insurance. Catholic Charities says they have retained a lawyer to help protest, but so far nothing has materialized. In the meantime, with donations she received, Carmen bought Musa an industrial sewing machine, but he can’t sit long in the requisite position. Walking to H-E-B sets him back several days. He tries to do some of the cooking for his wife, and he stays home with their youngest daughter who is not yet in school.

The responsibility for her family’s survival now rests entirely on Nama. She works full-time for a dollar above minimum wage. She gets $65 for teaching at the Weekend School. Yet rent for their two-bed/one-bath is $950 a month, plus utilities. And the Food Stamps that keep her children fed don’t pay for cleaning supplies or toiletries. The math never comes out in their favor, and because of the stress, Nama is now on blood pressure medication. When she talks about all of this, her fingers press together and point upward, pleading. She can handle the exhausting and menial work, the strange role reversals: “Just don’t leave me here,” she begs Musa—and God.

During Ramadan this past summer, though two other doctors had refused because of the danger, a surgeon at Memorial Hermann in the Medical Center performed a very risky surgery on Musa. He’s stabilized for now, but every six or eight weeks, he must endure treatments for varicose veins in his esophagus. Fluid collects in his abdomen, swelling it. The fluid may be contributing to the pain he feels in his chest. He is grateful for the care he is receiving, but he always feels in suspense. Though they’ve been lucky to have their Medicaid coverage extended beyond the typical eight months for refugees, it will end next summer; the cirrhosis will be with him for his whole life.

The hope to return to Syria—to Quneitra, if not to the house in the Damascus suburbs which was burned—is what keeps Nama alive. She thinks especially of one of her brothers, the only breadwinner left for the family there. He had been forced to join the military, but he escaped, which was a miracle. He couldn’t kill fellow Syrians, he said. Once he lived a prosperous life in Damascus. Now he sleeps with his wife and children in a tent in the Golan Heights. Nama says they live on oxygen. It may sound like a nightmare, but Nama dreams nevertheless of another miracle of escape, one where she can take her children and go running back.

*Not their real names.

The Horo Family

Mohammed Sheik Horo is trying to work out an arrangement of the American National Anthem for the buzuq, a long-necked, lute-like Syrian folk instrument he carried here from Turkey. He’s training himself by watching YouTube videos on his cellphone, listening to the words he can’t really understand, and the music underneath them. He moves his left hand up and down the neck of the instrument, which he’s plugged into an amplifier. With a pick in his right hand, he grazes a string at a time. The notes ache and linger, solitary, and though the melody of the “Star-Spangled Banner” is not yet fully recognizable, it’s there, like a shadow, like a figure walking towards you through fog, coming into focus. He knows he doesn’t have it yet, but Horo is disciplined. He’s giving himself one month to perfect the song. His goal is to have his five children sing it while he plays.

In the meantime, he’s made up a song of his own, one with a sense of forward movement and urgency, but also tinged with something dark and sad, as if written in a minor key. “America is a great place. America is a great place. Put your hands together to raise the American flag,” he sings in Kurdish, his native tongue tangled deep inside the melodic scales. “Texas is a good place. Texas is a good place. Houston is an even better one.”

Buzuq music, like Arabic music more generally, “is all about feeling,” says Michael Fares, a professor of Arabic at the University of Houston and himself a player of the oud, a similar Middle Eastern stringed instrument. “You establish one of the scales”—each of which has its own tone or mood—“and then you explore all of the ins and outs of that scale.” Arabic music is like jazz, Fares points out, which is like America itself in this way: it’s a great act of improvisation. All of which might explain why Mohammed Sheik Horo feels so at home here. Since the civil war started in Syria, he’s been making everything up as he goes along.

His family are Kurds from the countryside just northwest of Aleppo, in the Afrin region that borders Turkey. For generations, they had farms and worked their land and sold the produce—apple and pomegranate and olive and wheat, cantaloupe and watermelon. But as an ethnic minority whose traditional homeland leaked across borders into the modern nation-states of Turkey, Iraq, and Iran, the Syrian regime always feared the potential for Kurdish opposition. Many Kurds were stripped of their citizenship, and as foreigners in their own country, they were not eligible to work for the government, to vote or run for public office, to be granted a university degree, even to give their children Kurdish names. If they protested, they could be arrested or killed. Sometimes Horo tells his kids that he wishes he’d been born in America, where he’d have had less headaches, where he’d have had some rights.

And now there’s ISIS. They’re slaughtering the Kurds, Horo says, claiming that they’re not Muslim, that they’re infidels. But Horo recalls the story of Saladin, the great twelfth-century leader of the Islamic world who also happened to be a Kurd. Saladin’s brother urged him to do justice for the Kurds against outsiders, but Saladin told him, “Do not discriminate between Arabs and non-Arabs—only by piety.” A Muslim himself, Horo hates Muslims who spread violent destruction. He believes in love. And he thinks his music is the way to spread love in the world.

When Horo was eighteen, he moved to Aleppo to work as a tailor with his cousin, Jihad. Hanging on the wall of the shop, as on so many walls of homes and shops in Syria, was a buzuq, which Jihad would often take down and play. One day, Jihad found Horo trying to play, too, and he taunted him, saying, “You’re not smart enough to learn this instrument.” That only made Horo more determined. So at weddings, ceremonies that would be unrecognizable without the careening soundtrack of buzuq music, Horo would watch the band, watch how they played.

Sitting on the edge of the upholstered couch in his apartment in Southwest Houston, wearing a muscle shirt and cargo shorts, his round belly the mirror image of the belly of the buzuq, Horo plays the first song he ever learned. In it, a buzuq player remembers an old lover. On the table beside him is a glass of wine, and he starts to drink to try to forget her. “My heart was beating,” Horo sings, “and I wished I could see her in person.” Beside Horo as he sings is, in fact, Sureya, scarf lightly draped over her head and flung across her shoulders, the woman to whom he’s been married twenty years and whose name is tattooed in black ink, in Arabic letters, on his forearm. “I used to love her,” Horo sings. “He used to. Not anymore,” Sureya jokes. And Horo says, laughing, “I loved her to the point that I brought five children.” Sureya adds, “The love turns into a monster later!”

Back in Aleppo, back before Sureya even, Horo had started to save money from the wages he earned as a tailor and bought himself a house. When he and Sureya first married, they’d rented out the first floor and lived on the second. They slowly filled the house with their children—three boys and two girls. Once a year or more, they’d visit his parents in Afrin. It was, he says, a decent life.

But then came the revolution. Sureya remembers how, during the aerial bombardments in Aleppo, she would hurry the children into the bathroom in the interior of the house, telling herself it was safe there. But it wasn’t safe. She was just trying to do something to keep from feeling helpless. One day, Horo was standing on the balcony smoking a cigarette when a bullet whizzed next to his head. At the beginning of 2012, they left for Turkey with only the money to get them there. Ayendeh, the youngest child, was a toddler.

They went to Istanbul to meet up with some of Sureya’s family and lived at first in a house with her brother and many others—more than twenty people. When Horo finally found steady work tailoring and ironing, the family moved to a place of their own. The first night they slept on the bare floor, but soon their neighbors brought them furniture and other necessities. Still, Sureya didn’t like the Turkish people. “Where are you from?” they’d ask suspiciously. And they’d accuse her and the other Syrians there of being responsible for rising rents. Plus, her kids couldn’t go to school. In fact, to cover their expenses, the older three had to work—odd jobs, this and that for a Kurdish Turk—along with their father and Sureya herself, who sewed and ironed from home. Every day in Turkey Horo worried about the future, immediate and more distant: How am I going to feed my kids? What is going to happen to us? “I’ve been tired a lot,” he says now, remembering. “Tired from the inside.”

Life in Turkey was untenable. But once in Turkey, they never thought of going back to Syria. So the Horo family applied for refugee status. Originally Horo had asked to go to Germany, where his cousin Jihad had moved years before. In the end, though, it wasn’t Germany, but America that took them in. He knew nothing about the United States except for what people were telling him: that life was hard there, especially for refugees—harder than in other countries. But Horo replied, “Well, even to hell I will go. And if I get out, I will kiss the ground of that country.” He just had one question for the UNHCR personnel: “Am I going to be able to bring my buzuq with me? If not, I’m just going to stay here.” He was joking. But still. When he arrived at George Bush Intercontinental Airport in Houston in September 2015, brought here by Interfaith Ministries, he kissed the ground outside. Sureya, keeping him humble, says this was just a show for the kids.

For much of his first year here, Horo worked in housekeeping at a high-end hotel. Every morning, his co-workers—from Iraq and Syria and Latin America and the U.S.—would greet him. “Hello! How are you?” they asked. “Fine, how are you?” he’d respond. And then they all danced for a few minutes. “Disco,” says Horo. One of the few decorative items the Horos have in their apartment is a framed photocopy of a memo sent to hotel employees at the beginning of June congratulating Mohammed Sheik Horo for winning the company’s service award. “He is being celebrated for his commitment to the team and his positive and open attitude towards his coworkers,” says the memo.

Sometimes during the day, Mohammed would call Sureya and they would practice their English together. “Hello! How are you?” he would ask her. “Fine, how are you?” she’d respond. At night, he would come home from work exhausted. But he would play the buzuq, and sometimes the neighbors would sit outside on folding chairs in the narrow strip of grass between the apartment building and the fence dividing it from another complex, smoking shisha and listening.

When he plays the buzuq, Horo forgets everything. When he plays, Sureya remembers—Syria, their family, the past. She remembers gathering all together at parties and weddings, brothers and sisters and friends, before the war. She remembers how Horo would play the buzuq with other men in their neighborhood in Aleppo until three or four in the morning. She remembers how, when they came here, all of those people disappeared. But in remembering, for a little while, they are with her again and she leaves the pain behind. Sometimes when Sureya is most worried about her mother, ill in Turkey where Sureya can’t reach her, she lays her head on Horo’s lap and he plays for her until she falls asleep.

Once in awhile, Horo gets a gig playing the buzuq. His business card features him in hat and sunglasses—an echo of the Blues Brothers. Recently he performed at City Hall at a reception following a naturalization ceremony. Though he speaks very little English, he worked the room afterwards, handing out his card, smiling, joking, laughing. He had his picture taken with Ashley Turner, the daughter of the mayor. But in that setting, the music he played, separated from the culture it channels—the weddings, the streets of Aleppo—seemed in danger of becoming an artifact of a lost world.

On a recent fall day, he went with an Iraqi friend to Galveston to fish. Afterwards, they sat on the flat gray sand near the water drinking coffee. Horo was playing the buzuq. A young American woman who had been lying on the beach came over and asked if she could listen. She was, he says, beautiful as electricity: that essential, that much of a blessing. (“It’s not a big problem to talk to that girl,” Horo explains as Sureya listens. “It’s no problem,” Sureya says, rolling her eyes.) The men offered the American some coffee and Horo told her a little bit about the instrument. “It makes me feel so much at ease,” the woman told him. “It has such a positive vibe.”

What Horo would really like to do is make a lullaby for parents to sing to their children when they are going to sleep. He is trying to return the favor to America for helping him. In four or five years when he goes through his own naturalization ceremony and the city officials grant him his citizenship, he imagines that they are going to ask him, “Horo, what have you done for America? We have been giving you a lot of stuff—Medicaid, Food Stamps. Do something!”

He wants to make America a song.

Oum and Abu Bedawi and Oum Ghareeb

In Arabic, Oum means Mother. Across much of the Arab world, when a first son arrives, a woman takes on this honorific title that incorporates the baby’s name. Thus Oum Ghareeb, the Mother of Ghareeb. Thus Oum Bedawi, the Mother of Bedawi. The same goes for Abu, meaning Father. Oum Ghareeb and Oum and Abu Bedawi are old people beginning a new life in a city that does not know their names mean children who are lost to them, one way or another.

Actually, those aren’t their real names, but names they have given themselves because their real names, they fear, could bring harm somehow to those left behind in Syria and Jordan and Iraq. Ghareeb means “stranger” in Arabic, and Oum Ghareeb, nearing sixty, says she is a stranger here, outside her country, just as she felt herself to be a stranger within Iraq itself. There she was never free to find the good life that she desired. For Abu Bedawi, now in his seventies, the name he has chosen means “Bedouin”—those desert nomads of the Middle East—and it signals a painful truth: he has no home. The life he shared in Syria with Oum Bedawi and their ten children and their grandchildren is turning into memory. He doesn’t want to forget it, but it’s being forgotten. And now he feels himself to be a wanderer on the face of the earth.

These three arrived last fall, refugees sponsored by Interfaith Ministries, Abu and Oum Bedawi with their three unmarried sons; Oum Ghareeb with her daughter and her daughter’s family. They ended up in the same apartment complex on the Southwest side of Houston, amid a sprawling topography of low-slung strip malls with signs in Vietnamese and Urdu and Spanish—evidence of other immigrants who have indelibly shaped this city. The asphalt parking lot of the complex, the walkways lined with rust-red cinderblock half-moon pavers, the stunted palm trees pushing up from barren patches, the toilet-bowl-blue fountain near the creaking mechanical gate: this was now home. Interfaith Ministries had resettled Oum Ghareeb and Oum and Abu Bedawi here, alongside other Arabs because they share a language—although, coming from different countries, they speak different dialects.

With Islam, they also share a religion, though they belong to two different branches, between which exists a deep divide. Oum Ghareeb is Shia. Oum and Abu Bedawi are Sunni. But the Sunni-Shia split, they all agree, never mattered until recently. Sunnis and Shiites in both Iraq and Syria lived beside each other and worked together and intermarried. Oum Ghareeb and Oum and Abu Bedawi themselves cannot explain why this split now exists. But here in America, between them at least, the split is irrelevant. They are just grateful to have found one another. In this bewildering city full of signs they couldn’t read, the old rituals of friendship from their other lives had been broken. The apartment complex became their village. And English classes organized there gave structure to long, shapeless days, as well as some sense of connection.

Carmen Garcia, a volunteer originally with Interfaith Ministries who had begun to branch out on her own, could see that the caseworkers were overstretched with the wave of new refugees. She could also see that English classes—which refugee resettlement agencies are not responsible for providing—weren’t being organized. So Carmen got busy. Often, the Bilingual Education Institute, a local Houston agency, will set up shop within apartment complexes and offer classes for refugees, but here, there was no clubhouse in which the lessons could take place. Carmen convinced BEI to hold classes at a nearby community center instead. And at the complex itself, she also scheduled sometimes two or three sessions a day taught by volunteers in a rotating series of apartments.

One of those volunteers, Dr. Maria Curtis, is an anthropology professor who teaches courses on the Middle East at the University of Houston-Clear Lake campus. She knew Carmen from the Turkish Cultural Center, where Dr. Curtis and her husband, who is Turkish, would spend time with their daughters. She remembers getting the text message from Carmen listing the names and ages of the refugee children who had just arrived in September 2015. Seeing actual names, doing the math that told her some babies must have been born in transit, Dr. Curtis knew she wanted to help.

She’d done field work among women in Morocco and Turkey, but she’d never taught English. She thought she could spare just an hour a week, but quickly that hour morphed into two. Once she was teaching maybe twenty adults, all crammed in to the narrow living room of Oum and Abu Bedawi’s apartment, some with their backs pressed up against a window. The window broke and the crack woke a small girl sleeping in her mother’s arms. The girl, bewildered, began to cry, and all of the refugees, speaking different dialects of Arabic, rushed around the child and tried to soothe her.

But over time, the fathers and the young men found work, and the mothers with children in school lost focus. Attendance dwindled until it was just Oum Ghareeb and Oum and Abu Bedawi, three aged people with reading glasses perched on their noses, stringing together words into sentences like Christmas lights, practicing the Simple Past and Time Expressions: “I came to America last year,” Oum Ghareeb offered. “Before we go away from Syria, it was hard,” tried Abu Bedawi. “We go out from Syria month January in 2013.” He had a way of declaring each word as if it was emphatically and undeniably true, and when he reached the end of a sentence, it felt like he had achieved a great victory.

Abu and Oum Bedawi originally come from the village of Sahem El Golan in the southwest corner of Syria, just east of Israel and just north of Jordan, not far from Daraa, epicenter of the Revolution. They were there in 1967, during the Six-Day War, when Israel captured parts of the Golan Heights and displaced Palestinians streamed into the area, bringing with them, besides their sorrow, new vegetables the Syrians did not really know: eggplants and tomatoes. There had always been grapevines and olive orchards. Oum Bedawi raised cows and goats. Though a chemical engineer, Abu Bedawi farmed fish in a small pond on the side. Together they raised their ten children in a house that sat on the main thoroughfare. In their front yard they grew fruit trees and Damascene jasmine and roses. Little girls and boys on their way to school would ask permission to pick them. In the afternoons, people would nap. In the evenings, they’d gather in the street to talk and laugh and smoke. Life felt easy, uncomplicated. It was, as Oum Bedawi remembers, a paradise.

The fighting, when it started in 2011, spread like an oil slick on water and eventually surrounded them—rebels from the Free Syrian Army on one side of the village, military forces on the other. The home of Oum and Abu Bedawi got caught in between. On Google Earth, Oum Bedawi can point to the line of bullet holes on the stucco wall of her home near the kitchen window where she used to stand doing dishes and where, one day, a shot just missed her head. A bomb entirely flattened one of their son’s homes down the street, though no one was in it. In January 2013, the family fled to Jordan. Since then, the town has been fought over by ISIS-affiliated forces and rebel troops. At the moment, the rebels have control.

In the Zaatari Refugee Camp, Abu and Oum Bedawi and all of their children and grandchildren lived in UNHCR tents. The tents, that bitter January in 2013, flooded in the rains. Remembering the absurdity of this reversal in fortunes makes Oum Bedawi laugh from deep within her belly. After a month, they left for Irbid, a nearby city in northwest Jordan, and though she had six strong sons, they could not work for fear of being arrested or sent back to Syria. The education of her three youngest boys had been interrupted by the fighting—Abdul Malak had been a year away from becoming a teacher; Ibraheim was studying math in college; and Abdul Hakeem had been a senior in high school—but there was not hope of continuing their studies. When the call came that Oum and Abu Bedawi and these three sons had been approved for resettlement in the United States, they had to make the wrenching decision to leave their seven married children and their many grandchildren in Jordan. One son, at least, has since made it to Canada with his wife and children. The rest remain.

“Tears are their partners,” Abu Bedawi says of his wife and Oum Ghareeb sitting together on the standard-issue faux-leather sofa given to refugee families, as they look at photos together on their cell phones of their sons and daughters and grandsons and granddaughters, now scattered. They play videos set to whirling Arabic music, and think of the good things of the earth—olive trees and wheat fields and kibbe and yogurt. “Syria used to be a fruitful land,” remembers Oum Bedawi, even as the memory of it is disappearing.

Oum Ghareeb understands, though she is from the city, from Baghdad—not the countryside. She has never known anything but war, she says. She thinks of all of the wars that brought the displaced to Iraq and all of the wars within Iraq itself—Sunni versus Shia. She says that Iraqis like her are losing patience now and leaving.

She herself is Shia and lived all her life in the Karrada neighborhood of Baghdad, first as a child, then as a young mother, then as a widow. Because it’s largely Shiite, Karrada has been the target in recent years of countless terrorist attacks and car bombings perpetrated by the Islamic State and its affiliates. But it wasn’t always like this. Before the first Gulf War, as far as Oum Ghareeb can remember, neighborhoods were mixed. Families, too, even. The bombings picked up after Saddam was ousted. Oum Ghareeb once drew a map of the streets bordering her apartment building. The streets were pockmarked by those bombings. Once, too, she wrote a poem about the neighbors she and others would pull from the rubble, identifiable only by the clothes they wore or the rings on their fingers, fingers separated from hands. At least when Saddam murdered people, she says, you got the bodies back whole. That poem begins, “My son asks me, ‘Are we living now or dead?’” Oum Ghareeb, like her then-young son, is haunted by the bombings. On the news not long ago she watched as a woman in Kabul ran desperately, without even a scarf on her head, towards a building that had been bombed. One of her children was in that building. Oum Ghareeb wept as she remembered how this had happened to her, too, with one of her own daughters, the one still in Iraq, the one with the infant daughter Oum Ghareeb hardly got to hold before she left for America. She and her daughter FaceTime often, and Oum Ghareeb has had to watch her granddaughter grow into a toddler on her Samsung screen. She has no idea when she will see them again, if ever. Sometimes, now, when Oum Ghareeb is filled with emotion, she wants to write poems, as she used to. But the words have left her.

She has, besides that daughter, a son in Frankfurt—the one from the poem, now in his early twenties. He’s living in a hotel with other refugees and taking German classes. And then there’s another son in New York, who came to the United States years ago. And the daughter with whom Oum Ghareeb immigrated, along with that daughter’s husband and children. Though Oum Ghareeb and her daughter’s family had initially been resettled at the apartment complex with the stunted palm trees, among other Arabic-speaking refugees, they all moved out after their six-months’ aid was up, to a cheaper apartment even further down the highway, in a complex with no one else from the Middle East and no English classes.

Oum Ghareeb does love the nearby park in her new neighborhood, an open field bordered by woods and by levees that protect it from bayous straightened by the Army Corps of Engineers. She walks the paths in her black jilbab and flowered headscarf, carrying her handbag, sometimes with her two grandchildren, sometimes alone, and she says hello to the African American men in sweats, running in the midday heat, and to the clusters of Hispanic women. This place makes her happy. In Iraq, a green, well-watered park like this could never exist—not because of the desert but because the government would never invest in any good thing like this for its people, she says. Being here, she can see what she couldn’t when she was still in her country. Her thinking is different.

But she misses visiting her neighbors in Karrada and going shopping. She misses knowing where she is on the map, and how to get there. Her daughter has a car, but between her job cashiering at Walmart and her husband’s stocking shelves at the Dollar Store, someone is always using it, and Oum Ghareeb can’t drive. The buses this far out run infrequently, and anyway, where would she go? She doesn’t really have anybody to visit, except perhaps Oum Bedawi or Dr. Curtis.

Abu Bedawi says that if you cannot speak English you are like a mute person, and if you don’t have a car, it’s like you’re paralyzed. He himself stays in the apartment most days with Oum Bedawi and their youngest son, Abdul Hakeem, whose high school education ended when they fled Syria, and who is now too old to return to finish. He’s trying to study for the GED, but he struggles just to understand basic sentences. He had to quit a warehouse job because the family has only one car and their other sons’ work paid better. Abdul Malak found employment with a cell phone company. But with only street English, returning to the university to finish his education degree will be impossible. And the Syrian government won’t allow him access to his transcripts to prove what he has done so far. Ibraheim moves from restaurant to restaurant, though he is also taking English classes at the community college. Between Abdul Malak and Ibraheim, they provide for the family. And unlike their siblings stuck in Jordan, these sons at least have hope for the future. At the coffees that Interfaith Ministries sponsors for Arabic-speaking women, Oum Bedawi is, she says laughing, trying to find them brides.

For Abu Bedawi, though, there is no hope, there is no future. This journey was imposed on them. They did not choose it. Having to leave their country and their life—it’s as if they’re trying to complete someone else’s will. It’s inconceivable, what has happened to them, what they’ve lost, and they’re still trying to understand the powers behind all of this destruction and displacement. It’s like the ancient Marib Dam in Yemen, says Abu Bedawi. It stood for 1,200 years in the kingdom of the Saba people. When that dam broke down in 570 of the Current Era, the water took everything in its path. The Quran says that after the flood, the gardens of the Sabaens were replaced “with gardens of bitter fruit.” And that’s what happened to them. Everything Abu Bedawi built in his life was wiped out. Everything they lived for, everything they worked for was just gone. And now he fears that all he has to pass on to his children—those here, those trapped in Jordan, the one in Canada—is a heritage of pain.

Coach Lorenzo Barajas and the Monarcas

Most of the boys on the soccer team don’t really remember Syria, which they left three or four years ago. For the younger ones, that’s half a lifetime. They remember Jordan and Turkey better—the places they escaped to, in a bus under a hail of bullets, in a car at night, pulled out of sleep. They come from Daraa and Homs and Aleppo—cities of their fractured homeland—and also from Afghanistan and Congo and Sudan and Ethiopia and Nepal—other ruptured worlds. According to UNICEF, one in every 200 children on earth is a refugee. A couple of times a week, about 15 or 20 of those refugees play here, on this unremarkable field off Bellaire Boulevard in Houston, within a constellation of carnicerias and fruiterias and pupusarias, Vietnamese barbeque and pho places, liquor stores and cell phone stores and laundromats and shops offering passport services and gold buy-back, Diva Hair Braiding and Creole Soul Food, Bundu Khan Kebab House, mosques and churches and temples. On the southwest side of town, things feel in process, in motion: America coming into being, or America remaking itself.

Here’s how it started: A soccer mom already, Carmen Garcia recognized unchanneled chaos when she saw it: sinewy boys—Arab and African—chasing each other headlong over the black asphalt parking lot lined by palm trees in the low-slung apartment complex where Interfaith Ministries had recently settled these boys’ families. And Carmen knew what to do. This was in the early days, late last fall, when the Syrians were just beginning to arrive in Houston. Carmen, born and raised in East L.A., had come back from a trip to Turkey with her family a few months before, transformed. Outside of a mosque on the streets of Urfa, about thirty miles from the Syrian border, she’d met a girl, a Syrian refugee about the age of her own daughter, trying to sell earrings, which Carmen bought. Afterwards, Carmen got into the sleek Mercedes van in which they were touring, beside her sons and her daughter and husband, and she looked out the window and saw the little girl alone in the dusty street, and she said, “We have to help. We have to do something.”

And now she was. She’d basically adopted this entire apartment complex. She would pull in with donations or to check on the families, and she’d notice the fathers leaning against cars talking together, trying to figure out how to navigate this strange new world while their sons ran wild across the asphalt. After years of moving from place to place, or of living in refugee camps or in foreign cities with sporadic schooling, these boys needed order. They needed rules. They needed wide open spaces to run. They needed freedom. They needed soccer.

Carmen’s son played soccer in a competitive league in a more affluent neighborhood nearby, and for a while she watched his coach and thought about the refugee boys. Coach Lorenzo Barajas was from Mexico, a fairly recent immigrant himself. Though Barajas’s father had a Green Card and had brought his family to the U.S., where he worked for months, even years, at a time when Barajas was young, Barajas had raised his own children—three boys and a girl—in Queréndaro in the state of Michoacán. He was a PE teacher in Mexico—had been for twenty years. But the drug cartels were growing more entrenched, and life in Queréndaro was becoming more vulnerable. Innocent people too often got caught in the fighting between cartels, shot dead just walking across the street. When his kids left the house, he worried about whether or not they’d ever come back.

His brothers and sisters were already here in Houston—he’d been the only one who stayed in Mexico. But in mid-life, with his kids nearly grown, he and his wife decided to start over in a place where they would all be safe. At first, he worked with some of his brothers in their lawn care business. Recently he’s started his own company, and he’s trying to get certified to teach P.E. as well. He thought coaching soccer might eventually help his job prospects. Often he studies until midnight, then rises early to head out to his jobsites. His children are all studying at the university or else have completed their degrees—in journalism, business, architecture, and education.

In watching him with her own son’s team, Carmen liked that Coach Barajas never put the young players down; she liked his patience and perceptiveness. Eventually she approached him about coaching the refugee boys. She told him that the refugee families couldn’t drive, so he’d have to come to them. She told him the boys spoke no English, much less Spanish. She told him she didn’t know how much she could really pay him. Somehow she convinced him to take the team on.

They had their first practices in the fall of 2015. Barajas decided to call the team Monarcas International, the name signifying a certain longing in himself perhaps. The Monarcas—Monarchs in English—are his hometown soccer team. He added “International” because of the many countries his players come from. Monarcas are powerful kings, he points out, but also butterflies who migrate each fall from Canada south to Mexico—to Michoacán, in fact. Barajas marvels at the distance that these seemingly fragile creatures fly, how they reproduce, then die. But how, generation after generation, they just keep coming, wave after wave, seeking a refuge in winter.

For months, Barajas just had the boys practice. They were fast, but the Syrians especially had no coordination, no skills. And without English as a common language—among them they spoke Kurdish, Arabic, Farsi, Ethiopian, Congolese, Sudanese, Nepali—Barajas also wanted them to learn how to work together. Soccer became their lingua franca.

Sometimes, though, Barajas has to do some translation work. He’s noticed there can be a barrier between the Syrians and the Africans. The Syrians have a tendency to discriminate. They might complain that the African boys don’t pass to them. They will say, “They’re not the same as us.” If the kids are lined up for drills, a Syrian might veer out of the way of one of the Africans: “I don’t want to stand by him.” But Barajas refuses to accept this intolerance. “Hey, we are one team,” he tells them. “This is the United States. We all have the same rights. We are all human beings. We all have one God with different names.”

Besides old prejudices, some of the boys carry deep trauma with them that can take a toll. Carmen thinks of Aymon, one of the Syrian boys, who would be overcome with rage at the smallest slights and who decided that he simply wasn’t going to attend the tutoring sessions that Carmen had set up for all of the boys to help them with their English and with school. So one afternoon, Carmen sat down with him on the floor of the bedroom he shared with several of his siblings. She had a translator on the phone. She told him, through the translator, “You’re in America now. I can’t tell you what to do.” Aymon replied, “That’s why I like America!” Carmen said, “But here, whatever you do, that choice has consequences.” And she told him he couldn’t play in the game that week. On game day, Carmen picked up all the other kids and drove them to the field. A little while later, the players spied Aymon on some rinky-dink bike, pedaling determinedly towards them. “Aymon! Aymon!” they chanted together. He sat on the sidelines the whole game—and he never missed tutoring after that.

Over time, Carmen found a sponsor for the team, and purchased uniforms and balls and a set of game-day cleats for the boys whose parents can’t afford them. They practice on Saturdays and play games on Sundays. Once a season they have a pizza party. A new season started up this fall, and Carmen and Coach Barajas trolled the complex with a gaggle of translators, knocking on the doors of all of the apartments of recently-arrived refugees, filling out registration forms for them, laying out the rules on a poster board in Arabic, which they had the parents photograph on their cell phones: the boys must be at practices and games, they must keep up their grades, they have to attend tutoring. The refugees, who range in age from six to sixteen and are divided into three teams, pay nothing.