The young prosecutor approached the bench, laptop in hand, and stopped just to the left of judge Brandy Mueller. On the other side of the judge was a defense lawyer representing a man who had been arrested for drunk driving. The attorney asked the judge to approve the removal of a breathalyzer device called an ignition interlock that had been installed in his client’s car to prevent it from starting if the driver had been drinking. His client had complied for seven months with no violations, asserted the lawyer. The judge looked at the prosecutor. “Mr. Villalobos, what is the state’s position?”

“Your honor,” responded assistant county prosecutor Pedro A. Villalobos, “the state would like to bring to your attention that there was a collision in this DWI incident.” Then, consulting his laptop, which held the defendant’s criminal history, he said, “Also, there is something going on here with two possible previous DWI convictions.” Judge Mueller seemed annoyed. “That’s very relevant,” she said, turning her attention to the defense lawyer, who responded that he knew nothing about them. Mueller directed the prosecutor to look further into the matter—to find original sentencing documents—and see if the defendant was indeed a multiple offender, which would impact her decision. “Come back Friday,” she said. The bench conference was over, and both attorneys turned and walked away.

It was Halloween morning in County Court-at-Law No. 6, in downtown Austin, and Pedro, wearing a conservative dark suit, blue striped tie, and white shirt, stepped deliberately through the courtroom. He is short and boyish-looking, with a wide face, hair stylishly combed back over his brow, and eyes that look intently from dark framed glasses. Pedro works for the office of the county attorney, which prosecutes misdemeanors, from the minor (speeding, theft under $50) to the major (DWI, assault). He’s only had the job for a year, but he’s handled dozens of cases and worked sixteen trials. He’s taken eight cases before a jury and won six of them. Pedro is only 26, but if he’s nervous, he doesn’t show it, even when he’s representing the state of Texas in a room full of lawyers, deputies, and a judge.

Pedro is an undocumented immigrant, a Mexican by birth, an American by aspiration. For the last five years he has been a recipient of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, known as DACA, which was instituted by President Obama in 2012 as an executive action to defer the deportation of undocumented immigrants who were illegally brought into the country as children. Pedro didn’t know he was a lawbreaker. He was only three when his parents took him to Houston from Cuernavaca in 1994. Two years later Pedro’s father was sponsored for legal residency by his sister, a citizen; Pedro and his mother were also put on the residency application. He grew up with good teachers and mentors, and despite the constant threat of deportation, he prospered. “I’m lucky,” Pedro said.

However, just a year into his new career, Pedro finds himself in a desperate position. In September President Donald Trump rescinded DACA, and if no law is passed to replace it (Congress is currently embroiled in various possibilities), Pedro will once again be subject to deportation. He can’t be saved by his parents, who finally became legal residents and got their green cards in 2015 after nineteen years of waiting; Pedro was kicked off their application when he turned 21. He applied for residency himself in 2015 with his parents as his sponsors, but at this rate he won’t get a green card until 2034.

Pedro is not alone, especially in Texas, where roughly 113,000 people live with DACA protections. And without legislation to replace it, each will be faced with a decision: go back underground or leave the country. For Pedro—who dreams of justice and of making his community and state a better place—that could mean losing his job and eventually everything he’s worked for. “I call myself an American,” he said. “I’m an American in every way except on paper. I call myself a Texan. This is my home.”

What does it mean to be an American? After all these years, we’re still trying to figure it out. It’s not like there’s a DNA test. Most of us claim the right to be an American because we were born here. But America is a land of immigrants, and millions who came from somewhere else had to earn their citizenship. They’ve had to prove they belong, by time spent, hardship endured, principles honored: freedom, equality, the rule of law. Like citizens, immigrants found themselves stretching for the American dream—work hard, respect others, and the possibilities are endless.

For years lawmakers have seized on the passion of immigrants to earn citizenship—for themselves and their kids. By the turn of the millennium, a whole new generation of immigrant children was on the verge of graduating high school. In the spring of 2001, Dick Durbin, a Democratic senator from Illinois, seized upon the story of a teenage girl, born in Brazil, who had lived in the country illegally with her family since she was a toddler. She had become a piano prodigy, first playing in a Chicago church, later with the Chicago Symphony. She had wanted to apply to several of the country’s most prestigious music conservatories, but in order to attend with a legal status, federal immigration officials told her she would need to leave the country for ten years and apply for reentry. This was nuts, thought Durbin, who set out to help fix the system. The eventual result was the Development, Relief, and Education of Alien Minors (DREAM) Act, which would allow school-attending, law-abiding kids—Dreamers—an eventual path to citizenship. On August 1, 2001, Orrin Hatch, a Republican senator from Utah, formally introduced the legislation to the Senate, and gained eighteen Republican and Democratic senators signed on as co-sponsors.

Pedro is not alone, especially in Texas, where roughly 113,000 people live with DACA protections. And without legislation to replace it, each will be faced with a decision: go back underground or leave the country.

A month later, before the law had a chance to gain traction, the September 11 terrorist attacks changed the arc of the immigration debate. In the years that followed, much of the legislation introduced and passed by Congress pulled back on government benefits allowed to immigrants and attempted, somewhat dramatically, to beef up border security. Since 2003, following the creation of the Department of Homeland Security, the number of Border Patrol agents has doubled, and the number of ICE agents that handle deportations has nearly tripled. The focus of immigration legislation—and federal spending—had suddenly shifted to keeping immigrants out of the country, not creating a better system for the ones who had made a home here.

The Dreamers had fallen by the wayside. Versions of the act were brought before Congress in 2007, 2009, 2010, and 2011, but they all failed too, in 2010 by only a handful of votes. That year, many of the early champions of the legislation had withdrawn support, in large part because another shift had occurred: as the country’s economy busted in the latter half of the decade, the country’s political leanings took a hard turn to the right.

DACA was created by Obama on June 15, 2012, precisely because the DREAM Act was moribund. The action was almost immediately attacked as unconstitutional, and Obama himself said an executive fix was not ideal. He called DACA a “temporary stopgap . . . while giving a degree of relief and hope to talented, driven, patriotic young people” until Congress got around to passing a permanent version of the DREAM Act.

The law was designed for high school students, graduates, or military vets who had come to the country illegally under age 16 and who were under 31 when the law was implemented—and who’d never been convicted of a felony or significant or multiple misdemeanors. Unlike the DREAM Act, DACA offered no path to citizenship, merely deferring deportation for two years at a time. It also granted certain privileges: Dreamers could now legally obtain a work permit and get a job, go to school, receive a driver’s license and a Social Security card, and open a bank account.

Pedro was an ideal recipient. He grew up in Houston, where his mother began bussing tables while his father worked as a dishwasher. His parents were intent on Pedro getting a good education, and they sent him to Chinquapin Preparatory School, a private academy on the outskirts of Houston for low-income students. When Pedro got into the University of Texas in 2009, he thought about getting a degree in sports management—he loved sports but wasn’t good at playing them. He also got into politics, volunteering for Bill White’s gubernatorial campaign, knocking on doors and making calls. That led to working for other Democrats. He volunteered for the Obama campaign in 2012, and when DACA became law that year, he applied. His approval opened up all kinds of possibilities for the future, and Pedro decided to go to law school.

He was accepted into the UT School of Law and originally wanted to do immigration work. But after interning at the county attorney’s office, he fell in love with the hands-on problem-solving aspect of the law. He wanted to be a prosecutor. “People forget that as prosecutors, we can be good for the community,” he said. “This profession has a code of ethics that prosecutors have to live by. We learn it from day one. Our job isn’t just to get convictions, it’s to see that justice is done.”

Pedro didn’t want to be a law and order prosecutor, throwing the book at, say, a teen caught smoking a joint in a park. Much of the work of the county attorney’s office is working with low-level offenders and trying to gauge the logic of second chances. “We have to make sure we have all the facts, make sure the truth comes out and that we can determine the appropriate punishment. Sometimes we need to seek treatment instead of just throwing someone in jail. I’m not saying don’t put people in jail, but at the county attorney’s office we seek to make the community better.”

Pedro loves his job and has become quite good at it. On the morning of October 31, it was obvious he was a courtroom favorite, as lawyers, bailiffs, administrators—Americans all—greeted him, shook his hand, talked with him about cases, and asked what he was doing that night for Halloween. Judge Mueller, a former state and federal prosecutor, said of Pedro: “Seeking justice on behalf of the state, that’s what Pedro does. He’s capable, competent, hardworking, steady. He has a formal, professional manner I don’t see in a lot of people his age.”

Very few Americans, in fact, seem to be arguing for deporting people like Pedro. The same month that Trump rescinded DACA, throwing the issue of immigration reform—and the fate of the Dreamers—to Congress, a number of polls showed that Dreamers have overwhelming support. A Washington Post/ABC News poll, for example, found that 86 percent of Americans thought Dreamers should be allowed to stay, and Politico reported that more than half of the voting population wanted them to be eligible for some legal status.

But Trump focused much of his presidential campaign on a hardline approach to immigration, promising to build a border wall and create a deportation force. In February, not long after he took office, federal immigration raids took place across the country—51 undocumented immigrants were arrested in the Austin area. Since rescinding DACA, the administration has said that it’s up to Congress to find a solution, but it has also reinforced that border security should be a priority in any replacement legislation. Trump has at least hinted that he wants funds for the wall included, which DACA supporters insist is a deal killer. Both Democrats and Republicans have already introduced new versions of the DREAM Act, and at the end of November, Democratic lawmakers were promising to block any spending legislation if Congress couldn’t reach a solution by the end of the year. Still, it remains unclear how close they are to passing anything, and as DACA dies, the future of hundreds of thousands of people like Pedro is very much in doubt.

In late September, as the final deadline approached for renewing existing DACA applications, a dozen or so Dreamers came to a South Austin high school to file their applications so that they could keep their work permits and driver’s licenses until the program expires for good. It was a complicated application process, and a roomful of volunteers, including lawyers, social workers, and students from a group at UT led by undocumented immigrants, waited to assist them.

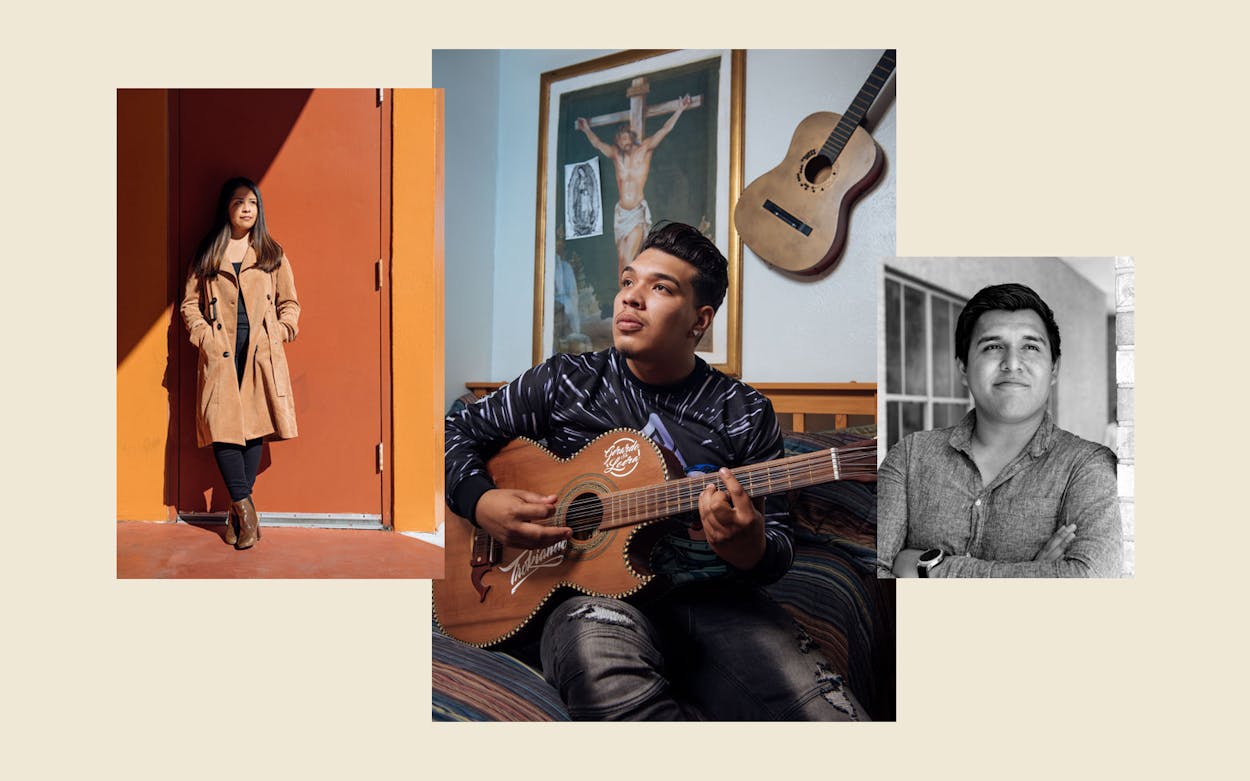

Pedro was there, and he chatted with some other Dreamers, who are friends of his. It was apparent how much they had in common. None of them had an accent; indeed, they all sounded like they had been raised in the suburbs. Most were from Mexico, though few remembered much about their homeland. Many were college students or graduates and nervous about Trump. “I cried all night long when he was elected,” said Jessica Chavez, nineteen, a UT student from Houston. DACA had enabled them all to get jobs—as waiters and clerks, or in the case of St. Edwards University student Joseph Ramirez, who is twenty, internships at the Austin Chamber of Commerce and the mayor’s office—that allowed them to pay for college.

They were all extremely smart. Vanessa Rodriguez, nineteen, was the salutatorian at Elgin High School before going to study government at UT. And they all felt obligated to help others—especially other young people like them. In high school, Vanessa won a State Board of Education “Student Hero” award for setting up a tutoring program. Joseph has already founded two Dreamer-oriented startups, the latest to help those who have lost their work permits become independent contractors. Pedro had raised money from local Democratic organizations and political donors to pay the $495 filing fees for every one of today’s DACA renewals as well as several more. “I felt obliged to use my position to help,” he said. “I’m in a position of privilege. I have a good job, and with my connections, I could raise some money.” The original goal was $10,000, Pedro said, but they ended up raising $50,000.

Eventually the volunteers made their way to the school cafeteria and took up posts at the lunch tables, waiting to help with DACA renewals. Soon the applicants were brought in, one to a table. Gerardo De Loera, 20, sat next to his mother and younger sister. Gerardo had a scruffy beard, and he wore a black T-shirt and black Chicago Cubs cap. He was born in a small town in the Mexican state of Aguascalientes and brought to the country at two. He hunched shyly over the table toward his interviewer, a young woman, as she asked a series of questions in English.

“Have you ever been apprehended by the authorities?”

“No.”

“Have you ever gone to jail?”

“No.”

“Have you ever received a ticket?”

“No.” Gerardo paused. “Well, I did get one. I was learning to drive with my mother in a parking lot and got stopped. But my mother got the ticket.”

Gerardo signed up for DACA soon after it became available, when he was sixteen. His mother had saved up for the filing fee. With his work permit, Gerardo got a job as a janitor at the state capitol and would bike there after school, work until 2 a.m., then ride home and get up the next day for school. He graduated in 2016.

Instead of college, Gerardo decided to try a career as a musician. “My parents thought I’d get into rap,” he told the interviewer. “But I play traditional Mexican music.” Gerardo, a self-taught guitarist, learned to play listening to the old-school folk music from Mexico that he heard around the house growing up, music his parents played on the stereo. He especially loves narcocorridos, ballads about the drug outlaws of his native country. He writes his own based on news accounts and stories he hears from people who’ve gone to Mexico. It’s his way to stay connected to his homeland.

Gerardo makes a living playing his guitar at parties and clubs, both solo and with his three-piece band (six-string guitar, twelve-string bajo sexto, and bass). “I’m actually going somewhere with this,” he said. He’s ambitious—playing all over Austin but also as far as Waco—and has on his Facebook page more than a dozen of his own tunes and covers, including a couple of love songs. He sings in a high, clear voice and strums and picks the guitar with a chugging rhythm. Like every other young Austin musician, he’s working on a demo.

After the consultation with the volunteers, Gerardo, his mother, and his sister went to the next station, where he talked with an immigration lawyer, who quizzed him on the traffic stop and various other matters, such as what would happen if he returned to his place of birth. “Do you fear harm in Mexico?” she asked.

“Not really,” he said. “Except that I’m a musician. I write songs, I write narcocorridos, and some places you can’t sing them or you get killed.”

Finally he was done, and he signed the paperwork and received a money order made out to the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services for $495. Gerardo’s mother drove him to FedEx to drop off his renewal application before hurrying home. That night he had a gig at a ranch near Elgin, and he had to get ready.

There’s nothing more American than wanting your kids to do better than you, and one of the most striking features about Dreamers is their feeling of a debt owed to their parents. Vanessa is still consumed by something her undocumented father told her when, at age six, she accompanied him one day to his job digging trenches to lay pipes for outdoor swimming pools. When Vanessa asked how she could help, he replied, “You could do well in school.” So she did. “I know everybody loves the Dreamers,” she said, “but I love my parents, and they’re the original dreamers, and I don’t think I deserve something more than they do. They value this country as much as I do.”

Juan Belman felt so obligated to his parents that he confronted President Obama about them when he came to Austin on July 10, 2014, to give a speech at the downtown Paramount Theatre. Juan—a DACA recipient whose father had almost been deported—and his brother Mizraim, who was sixteen, stayed up all night to get tickets, then sat five rows back in dress shirts and ties. When Obama mentioned immigration near the end of the speech, the Belman brothers stood up. “Stop deportations!” they called out. “Expand administrative relief!” They chanted it several more times, getting booed and shushed from all sides, until Obama motioned in their direction. “Sit down, guys,” he said. “We’ll talk about it later, I promise.”

Juan, born in 1992 in the small Mexican city of Santa Cruz de Juventino Rosas, was snuck across the Rio Grande by his mother when he was ten; the family settled in Austin. Juan fell in love with American culture, becoming fluent in English at thirteen, playing trombone in his junior high band, throwing a football, swinging a tennis racquet, listening to Green Day. By his senior year, he was doing yoga and studying math and physics. But he wasn’t a typical Austin teen. He couldn’t get a job or a driver’s license. Getting stopped by the police could mean deportation. “It was nerve-wracking,” he said. “But I knew that I had to get good grades to do well in school and make my parents proud.” His mother never even attended high school, and his father dropped out in ninth grade, but Juan saw how hard they worked, how they learned to thrive in a foreign country. Juan became one of the top ten students at William B. Travis High School and got into UT. A science nerd, he decided to major in aerospace engineering in hopes of eventually working for NASA.

But right after he started classes, in September 2011, his father—whose work permit had expired—was detained in Abilene, where he was doing a job with a construction crew. They had been stopped because one of the other four men wasn’t wearing a seat belt, and when he couldn’t produce an ID card, police took the whole group to the station and called U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement. The immigration officers instructed the men to sign orders of voluntary departure, which gave them 60 to 120 days to leave the country. Everyone did, except Juan Sr. As a result, he was sent to the Pearsall detention center, leaving Juan to figure out what to do. “I was lost,” Juan said. “I didn’t know how to figure out who’s a good lawyer, how to help my father.” Juan eventually got an attorney, who arranged bond for his father after a month.

President Obama kept his promise to Juan, talking with the brothers backstage. Juan told him that he was a DACA student but that their father had been detained and almost deported. He thought it was imperative that the president make another executive action for adults too, people like his parents who had come to America illegally but who had built good lives here. Obama heard him out and responded that the best way to deal with the problem was through legislation and that the brothers should focus on convincing Republicans to pass permanent immigration reform—like the most recent attempt in 2013, which would have codified many elements of DACA and also created a path to citizenship for children and adults. Although sponsored by four Republicans and four Democrats, it too had failed. “We weren’t satisfied at all,” Juan said. “Obama gave us the political talking points he was saying at the time.”

Still, Juan is proud he and his brother stood up to the president to try and help his mother and father. He is 24 now, with a shy smile that reveals braces, and he speaks carefully, with a slight Spanish accent. “I think that us Dreamers realize the sacrifices our parents made,” he said. “They left everything behind—their families, homes—to give us a better future. I feel I need to seize the opportunity and do well so they know all of that was worth it.” These days Juan works as a legal coordinator for a nonprofit that does immigration work. He eventually wants to go to law school or grad school to get a policy degree. But his DACA protections expire in February 2019, and without a work permit he won’t be able to get a job to pay for school.

Juan lives in a crowded two-bedroom apartment in South Austin with his parents and his two youngest brothers, Sammy, 12, and Noah, 3, who were born in Austin and are American citizens. Juan and Sammy share a room, and when Mizraim, now a sophomore at Georgetown University, comes home on breaks, he joins them.

On a recent Sunday afternoon, Juan and his youngest brother, Noah, sat in the living room with Juan Sr., 51, and their mother, Sara, 45. They had recently come from church, where Juan Sr. is a lector, reading from the Bible, and he and Sara help with the Eucharist. Juan was visibly excited. A friend had given him a day pass to the Austin City Limits Music Festival, and he was trying to decide which band to see that evening: the Gorillaz or the Killers. While Noah played on the carpet with a couple of toy cars, Juan translated for his parents as they talked about their lives in Mexico and Texas.

Juan Sr., like Sara, was born in Santa Cruz de Juventino Rosas, where he was the oldest of ten children and had been working to help his family since he was six. They arrived in Austin in 2003 and loved the city. Juan Sr. had a work permit, but Sara had no legal status. She was especially nervous when she started driving, because she had no driver’s license. But the couple was determined to raise their children as if they were a normal family, showing them as little fear as possible.

Then came Juan Sr.’s detention in 2011. Though he was terrified, he refused to sign the voluntary departure order. “The person filling out the documents intimidated us,” said Juan Sr. “He said we couldn’t stay here. But I refused to sign. My family was here.” He looked at Juan. “It was your first year at UT. All that would crumble if I was sent back.” He spent a harrowing month behind bars. His wife and two elder sons couldn’t visit because they didn’t have documents and could also be detained. After their lawyer got him out on bond, the case dragged on for two years in federal immigration court and was finally dismissed. He now has a work permit that he must renew every year.

Every year has been rough for the Belmans, and this past one has been no different. First there was the election of Trump, then came the February raids. For weeks afterward, Sara rarely left the apartment, terrified of getting picked up on the street by ICE agents. Then came the announcement that DACA would be ending. Now her two eldest sons will soon be in danger again.

But as they’ve done for fourteen years, they carry on. And as Americans have done for generations, they dream. More than anything, Sara wants to own a home. The Belmans have been saving their money and looking to get out of their cramped apartment. By then they hope to be on the road to some kind of citizenship. They can wait until Sammy turns 21, when he can petition for citizenship for them, though that would take many more years. Their best hope is through a U visa, designed largely for victims of violent crimes, for which Juan Sr. qualifies because in 2015 he was robbed at knifepoint outside an Austin church. He applied after cooperating with law enforcement, a prerequisite for the U visa. If he is granted one, he can then apply for permanent residency—as can Sara and Mizraim. Juan, who was over 21 when his father was robbed, cannot. “That’s their best hope,” said Juan.

What does it mean to be an American? Is it enough to prove that you are hard-working, ambitious, resilient, brave, ingenious, loyal, and a longtime member of your community?

He ate an early dinner and got his bike ready for a ride downtown to the music festival. He said goodbye to his parents. As he pushed off, he was still trying to decide which band he wanted to see.

What does it mean to be an American? Is it enough to prove that you are hard-working, ambitious, resilient, brave, ingenious, loyal, and a longtime member of your community? Juan would like to think so, as would Pedro, Vanessa, Joseph, Jessica, and Gerardo. All they can do now is wait and see if Congress in fact moves beyond DACA so they can someday become actual Americans. The truth is, nobody, not even the Dreamers, will miss DACA, at least if Congress finally passes some version of immigration legislation. “DACA was a great opportunity to legally work,” said Jessica, “to get a driver’s license, to feel like we belong. But it was just crumbs. There was no way to become a citizen.” Megan Sheffield, an Austin immigration lawyer, thinks there’s an opening now for actual immigration legislation. “I’m disappointed DACA is ending,” she said, “but it was just a band-aid. We need a path to citizenship.I’m hopeful some kind of DREAM act will pass, and we also need comprehensive immigration reform to provide coverage for the entire community of undocumented immigrants.”

What Dreamers and their parents really want is a change to the whole immigration system, which is cumbersome, out of date, and nonsensical. Pedro gets exasperated when he thinks about the hurdles put in his and his parents’ way to get a green card. “Why do we have a system that requires someone to wait nineteen years to be a legal resident?” he asked. “I would have become a legal resident or citizen by now if I’d had the opportunity.” Though Pedro’s application is filed, Juan can’t even apply until Sammy turns 21, which would mean, at current rates, that he might get approved by 2045. At this point, the best hope for both men to stay in the country is to marry a citizen—and petition to get a green card. But neither imagines a wedding anytime soon. “If I’m going to marry someone, it’s because I’m going to be with her for the rest of my life,” Juan said. “Coming from the Catholic Church and a religious family, it’s very important I don’t separate from my partner. Seeing my parents so happy today, it’s something I want too.”

None of the Dreamers can imagine returning to Mexico, a country as foreign to them as it is to most Americans. Pedro’s one connection to the old country is that he enjoys cooking authentic Mexican food like mole and chile rellenos. In his spare time he likes to cook for his friends, as well as binge-watch TV shows on Netflix and collect vinyl albums (his favorites are Pink Floyd, Fleetwood Mac, and Neil Young). Pedro tries not to think about what would happen if he were actually kicked out of the state that he represents in court every day. Practically speaking, he’s too busy, but he also admits that he is in denial. “It’s something that I don’t want to think about,” he said. “What do I do with my car loan? I can’t save for retirement anymore. I’d have to give up this job that I really, really love.”

But occasionally he thinks about the reality of his situation. He can’t help it. He believes he’s earned citizenship and can’t imagine what else he could do to prove that he belongs here. He went to college, he got his law degree, he works, he pays taxes, he’s stayed out of trouble. He’s done everything he’s supposed to do. But as he walks his dog, Lady Bird, through his West Austin neighborhood and thinks about what would happen if his dream came true and he officially became an American citizen, he knows that nothing would really change. “My relationships with everyone I know would stay the same,” he said. “My neighbors, my friends, the lawyers at the Austin Bar Association, the people at work. The other prosecutors, the defense lawyers, the legal secretaries, bailiffs, administrators, judges—they value me for my work ethic and the type of person I am. All I’d have is a piece of paper saying I’m a citizen.”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Longreads